Does it look like other UW buildings or athletic facilities? No. It has a barn-like style and is made of wood, with cedar shingles covering the exterior walls that slope slightly up toward the high roof. The daughter of 1936 gold medal rower Joe Rantz, ’36, Judy Rantz Willman, recalls being in the shell house with Dan Brown while doing research for his “Boys in the Boat” book.

“We were looking around at mostly canoes but feeling the thickness of (the shell house),” she recalls. “Just being able to look around, it was kind of enough to make the hair on the back of your neck go up. ‘Gee whiz, this is where it all happened!’”

While the shell house is often locked, you can sign up for a weekend tour offered by former UW rower Melanie Barstow, ’16. You will get the opportunity to see the 10,000-square-foot interior that looks so much like it originally was. “We’re here in 2019, and it’s the same,” Cohen says. “It hasn’t changed. You feel like you’re touching history when you’re in that building because so little of it has changed.”

“You walk in and all your senses trigger,” adds Nicole Klein, who is spearheading an effort to explore renovating the facility into a mixed-use space that could host students, and special events while being surrounded by interactive exhibits and timelines that share its rich history. “Some people would say this is a sacred space. To others, it’s a place they adore and reflect fondly on. And others had never been allowed in, so when they walk inside, it feels like you let them into the Secret Garden.”

A Husky crew gives its all while practicing on the Montlake Cut as seen from the interior of the ASUW Shell House

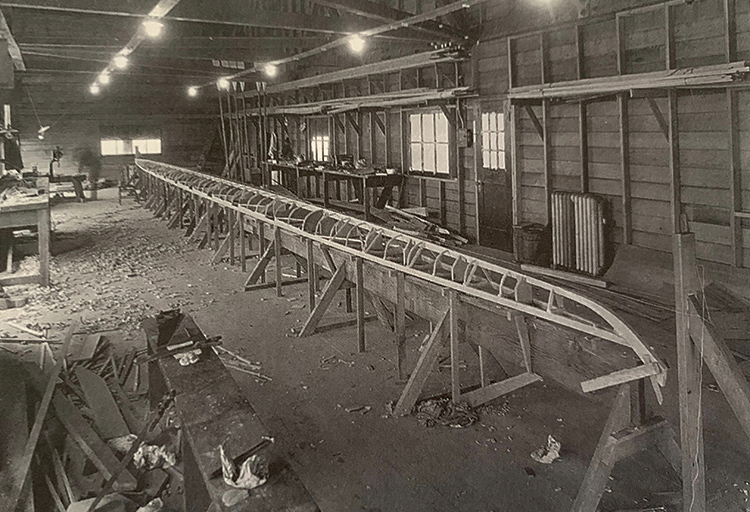

Inside the ASUW Shell House, you will see the historic wood rafters near the ceiling that will leave you awestruck. You can walk up the stairs to the mezzanine level, where the legendary George Pocock constructed and worked on rowing shells for decades, including making the “Husky Clipper,” which the UW team used to win the 1936 gold medal. “You can feel George Pocock’s presence in there,” Cohen says.

David Strauss, assistant professor of architecture, says that what is exciting about the building is its lightweight wood structure. “It’s like a temple to Northwest building materials,” he explains. Strauss is helping with UW Recreation’s plans to assess renovating the ASUW Shell House, which the organization says could “bring campus back to water.”

In addition to the famed Husky rowers, Sally Jewell, who served as the U.S. Secretary of the Interior for President Obama, worked in the Canoe House when she was a mechanical engineering student at the UW. She said it was one of her fondest experiences at the UW.

“Our campus is unique in the world for many reasons, but one important aspect often overlooked is our expansive waterfront,’’ Jewell, ’78, wrote in an email. “Restoring this historic landmark, could enable us to celebrate our relationship to the waters that surround us, and the history that has shaped our region from indigenous communities to the present. A national and local treasure, the ASUW Shell House is an artifact layered with our collective histories which celebrate our deep and lasting ties to the natural world.”

Judy Willman said that she would like the renovation to retain the look and history of the shell house. She isn’t alone. “Everyone that we brought through, no one wants to get rid of the exposed beams,” Klein says. “Everyone wants to see it look like as much right now as it did in the heyday in its 1930s as possible.”

“The ASUW Shell House is a University of Washington rowing icon,” UW men’s rowing coach Michael Callahan, ’96, adds. “It is a symbolic treasure representing the history and success of our student-athletes and alumni far and wide.”

To learn more about the future of the ASUW Shell House, please visit www.asuwshellhouse.uw.edu or call (206) 221-8517.

Related story

The century-old ASUW Shell House is where the ‘Boys in the Boat’ became a team.