Can’t hold him back Can’t hold him back Can’t hold him back

From radical youth to senior statesman, Larry Gossett is an activist for us all. The 2021 Alumnus Summa Laude Dignatus award recognizes his lifetime of service.

By Hannelore Sudermann | Photos by Rick Dahms | June 2021 issue

The Alumnus Summa Laude Dignatus is the highest honor bestowed upon a UW graduate and is presented annually by the UW and the UW Alumni Association. It recognizes a legacy of achievement and service built over its lifetime. More than 70 alumni who personify the University’s tradition of excellence have received this prestigious honor since the award was inaugurated in 1938. The list includes Nobel Prize winners, internationally recognized scientists, artists, business leaders, educators and many other influential figures.

You can’t really talk about the UW in the 1960s without mention of Larry Gossett. A student activist who helped organize the Black Student Union on campus, he formed tight bonds with his classmates and sparked a massive effort to make the University more diverse.

Gossett ranks among Edmond Meany (class of 1885), Trevor Kincaid (class of 1899 and 1901) and Bill Gates Sr (class of 1949 and 1950) as alumni who transformed the University for generations to come. While his predecessors established the campus, founded the zoology department and a research station, and drove innovation and public service law, Gossett and a small group of fellow students motivated the UW to expand its curriculum and recruit and support first-generation students and students of color. They also prompted the school to hire more faculty of color. The results of their activism enriched the college experience for everyone, not just underrepresented and economically challenged students.

But that’s just part of why Larry Gossett is this year’s Alumnus Summa Laude Dignatus (alumnus most worthy of praise), the highest honor the UW confers on its alumni.

Thousands know him as a human rights activist, a leader who crossed cultural lines to support women and people of color through acts of civil disobedience.

Nearly 200,000 Seattle-area residents know him as their King County Council member. For a quarter century, until 2019, he represented a sizable segment of inner-city Seattle from the University District down to a patch of unincorporated county north of Renton. As a politician and public servant, Gossett was ahead of his time in calling out systemic inequities, pushing to change racist iconography and opposing the racial discrepancies in the justice system—the very things our nation is grappling with today.

And many others have come to know him as a caring friend. Someone who would jump up from a planning meeting to visit a constituent’s grandson in jail.

He would also pull a few dollars from his pocket to help anyone cover bus fare.

* * *

Larry Gossett didn’t start out wanting to change the world. But the moment he stepped foot in Harlem in the summer of 1966, that was his mission. The New York neighborhood, a mecca for Black America, was a center for racial pride. Profound influences like Malcolm X (who had been assassinated the year prior) and sociologist Preston Wilcox helped the community recognize its biggest challenges: oppression, discrimination and social and economic exploitation.

Into this world came a 20-year-old clean-cut college student from Seattle, eager to address urban poverty and learn more about Black America. Gossett was a solid student and basketball star at Franklin High School who enrolled at the UW in 1963 in the midst of the Vietnam War. He wasn’t thinking about much except earning a degree that would land him a good job. As a junior, he joined AmeriCorps through VISTA (Volunteers in Service to America) and was assigned to Harlem, what the government was then describing as a “pocket of poverty.”

Gossett discovered a far different Black America than what he knew in Seattle. His hometown had a Black population that numbered around 30,000. In Harlem, where the population topped 100,000, each city block was home to thousands. “And most of them were poor,” says Gossett. “I wondered, why does this exist in my country?”

He fed his understanding with books, starting with Black history. The bookstore clerks pushed him to read about non-Black revolutionaries as well, developing his understanding of race and economic-based injustice. He started thinking about the exploitation of one class by another. “I just changed very, very rapidly,” says Gossett. He became self-analytical and observant. He also altered his appearance, growing his hair and donning sunglasses and dashikis. He asked people to call him Mohamed Aba Yoruba. By the end of his time there, he considered himself a Black revolutionary.

“I became very serious about using the opportunities I had to ‘liberate’ Black people. We thought we would be dead or in jail by 25.”

Larry Gossett

He could have stayed to support the revolution from the heart of Black America, “But I wanted to do the work at home in my own community,” he says. “So I caught my plane on Sept. 17, 1967.”

Gossett was a new version of himself not just in looks, but in attitude. At the airport, his mother and youngest brother walked right by him, he laughs. Once home, he reached out to his UW friends and discovered that, like him, they were ready to embrace racial pride, seek social and economic empowerment, and celebrate Black history and culture.

Over the next few months, the students made trips to two different meetings in California where they encountered other students, activists and the Black Panthers. At the end of the first trip, the UW contingent established a Black Student Union on the bus on the way home. “We couldn’t wait,” says Gossett, who was selected as regional chair for Washington and Oregon’s BSU.

On Jan. 6, 1968, at the start of winter quarter, 13 UW students announced the formation of the BSU on campus. The group called out the administration, pointing out that there were few Black students and teachers, the UW offered no classes in Black history or culture, and no class used texts by Black authors. “It shocked me, but it didn’t surprise me,” Gossett says of the oversight.

In the spring, BSU activism landed Gossett and other classmates in the King County Jail. They had gone to Franklin High School to support students in a sit-in to draw attention to racism from teachers and the principal. Two days later, the police knocked on the Gossett family’s door at 7:30 a.m. Larry wasn’t home, and they arrested his brother. Once he learned the police were looking for him, Gossett went police station with a member of the UW faculty to turn himself in safely.

That afternoon, news about the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. reached the jail. Gossett, Carl Miller, ’74, and Aaron Dixon—who had, because of their activism, earned a degree of respect from the other inmates—talked the prisoners out of fighting with each other. The UW students explained that King was an activist for everyone struggling with injustice and social and economic disparities, regardless of color.

Their trial for unlawful assembly was ultimately a debacle. A seven-minute jury deliberation delivered a guilty verdict and of one the harshest sentences ever given to peaceful demonstrators—six months in the county jail. The verdict roiled the Black community, sparking several riots. Fortunately, the men were quickly released on appeal and new charges were not pursued.

Gossett’s brush with the law only intensified his activism. “I became very serious about using the opportunities I had to ‘liberate’ Black people,” Gossett says. He was ready to put his life and his body on the line. “We thought we would be dead or in jail by 25.”

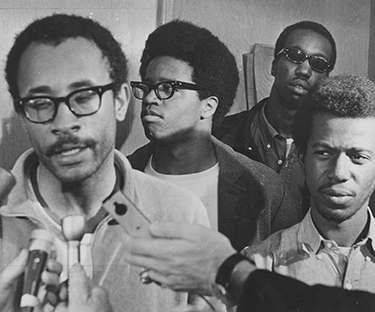

UW BSU President E.J. Brisker (left) and members Larry Gossett (center), Chester Northington, and Carl Miller speak to the press after a sit-in in President Charles Odegaard’s office on May 20, 1968.

In May 1968, Gossett and a group of Black, Latino and Native American students and their white classmates joined members of the greater community to march on the Administration Building (now Gerberding Hall), climbing the central stairway and taking over President Charles Odegaard’s office. They brought a list of demands that included recruiting and supporting more students of color, diversifying the faculty and delivering a Black studies program. After a nearly four-hour sit-in, with more than 70 police officers and a growing numbers of sympathizers gathering outside, the demonstration ended peacefully shortly before 9 p.m. Odegaard had agreed to their demands.

Ultimately, the BSU found an ally in Odegaard. “He had a better understanding than most of the whites on campus,” says Gossett, “But he thought we were moving too fast.” In answer, Gossett and his BSU classmates argued that after centuries of oppression and stolen opportunity, the time for change was long overdue.

That 1968 sit-in motivated Odegaard and his administrative team. By that fall they had started the Educational Opportunity Program for low-income and first-generation students, founded the forerunner that became the Office of Minority Affairs & Diversity (OMA&D), accelerated the hiring of faculty of color, and developed programs in African American studies, Asian American studies and Indian studies.

By 1975, the number of Black students on campus had grown from 63 at the time of the sit-in to 1,666, says Gossett. They were joined by 800 Chicano/Latino students and at least 200 Native Americans, he says. Ultimately, Odegaard and his administration had delivered on recruiting and funding for scholarships and organizations. “I had a deeper appreciation of him by the time he died in the 1990s,” Gossett says. In fact, Gossett spoke at Odegaard’s funeral at the request of his family.

* * *

The UW was just one of Gossett’s arenas. In addition to joining the Black Panthers and working as a labor and human rights activist in greater Seattle community, Gossett formed an alliance with three other activist-leaders in Seattle’s communities of color. “We met in struggle,” says Gossett of friends Bernie Whitebear, Roberto Maestas and Bob Santos. Santos represented the Asian American and Pacific Islander community, Whitebear (Sin Aikst) was a leader in the urban Indian movement, and Maestas, ’66, ’71, was a teacher at Franklin High School who became an activist and co-founder of El Centro De La Raza. By supporting one another’s causes, they changed the landscape of the greater Seattle community.

“We just clicked,” said Maestas in a 2009 interview with KCTS-TV, Seattle’s PBS station. “Before you knew it, we were buddies, like brothers.” The system had somehow always pitted one group against the other, says Gossett. Once they started showing up for demonstrations or negotiations as a multiracial group, they struck fear in the heart of the Seattle establishment. A few phone calls could bring out 300 to 400 demonstrators.

Gossett also worked in the UW’s newly formed Office of Special Programs, the precursor to today’s OMA&D. One spring day in 1973, an undergraduate named Rhonda Oden, ’75, strolled into the office. Gossett, who was overseeing the academic counselors, set about connecting her with an adviser. Later, he asked her out. The pair married in 1975.

By then Gossett had left the UW to focus more on activism and community organization. He joined the Central Area Motivation Program as a consultant and by 1979 became the executive director. It was a community-driven service organization focused on reducing the impact of poverty by providing food, shelter, education support, employment and training. It was a welcome contrast to the institutional structure of the University, says Gossett. While ensuring that CAMP served the community, he also encouraged the people he met there to become involved in public issues.

1984 was also a life-changing year for Gossett. His service as state chairman for the National Rainbow Coalition, a multi-ethnic campaign to make Jesse Jackson the Democratic presidential nominee for the 1988 election, brought Black activists and non-voters of all ethnicities into the Democratic Party. They started to reshape it. The Rainbow Coalition transformed the idea of how to gain political power in Seattle, Washington and nationwide—while also transforming Gossett’s thoughts about politics. “And by then the bug had bit me,” he says.

Fifty-three years ago, Larry Gossett and other members of the Black Student Union climbed the steps of the Administration Building to mount a sit-in and demand that the UW do more to recruit and support students and faculty of color. Gossett has since had a long career as an activist and elected official.

Today Alexes Harris, ’97, is a sociology professor at the UW. But when she met Gossett in the early 1990s, she was a Garfield High School student who, along with many of her classmates, wanted to do something about recent killings of people their age. Gossett encouraged her to help organize the annual Martin Luther King celebration based out of her school. “Larry just always wanted to engage with young people around politics, around advocacy and around community engagement,” says Harris.

She volunteered in 1993, when Gossett decided to run for King County Council. The district—where he worked, lived, had gone to school and was an activist—was the perfect fit. As the campaign volunteer coordinator, she witnessed Gossett building relationships across ethnic lines and outside of the standard political structure. “Larry was not part of the African American sort of establishment,” says Harris. “He was told it wasn’t his turn to run. He wasn’t the polished candidate that some people thought should run.”

But the neighborhoods saw it differently. As Gossett and his campaign went door to door, made phone calls and sent out mailings, his support grew and he won with record voter turnout. “It was truly one of the best grassroots electoral campaigns,” says Cindy Domingo, Gossett’s campaign manager and later his chief of staff for King County.

“He has a passion for those who have the least and are the most oppressed,” adds Domingo, who first met Gossett at CAMP. “He has no hesitation to take money out of his own pocket to help someone out.”

Gossett’s major causes included homelessness, human rights, issues around immigrants and refugees, and criminal justice. In 1997, the council was ready to enact a $100 booking fee for everybody in the jail. When it came time for the final vote, Gossett halted the process. He asked for a week’s delay and used the time to invite women and men already in debt to the court to testify before the council. “I knew they could not afford another $100,” he says. “Why add to that for no reason?” Then he presented findings from his office that the county was already owed $366 million in unpaid legal financial obligations. It was enough to persuade two fellow council members to change their votes and kill the fee.

While the effort to remove public art and symbols of racism has spread to nearly every state and campus today, Gossett was ahead of his time in pushing for this change in King County. The original county logo was a crown that honored Vice President William Rufus DeVane King, a 19th-century proponent of the Fugitive Slave Act who enslaved people at his own plantation in Alabama. In 1986, the county council voted to instead honor Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., whose public service achievements were more in line with the county’s own priorities. But the crown lingered as the county’s symbol well after Gossett took office. In 1999, Gossett proposed dropping the imperial crown in favor of a likeness of MLK. It took substantial effort and argument, but Gossett eventually won the support of enough fellow council members and, 20 years after the namesake was changed, the logo followed suit.

“When you are representing the disenfranchised, you have to govern in a different way.”

Girmay Zahilay, King County Council Member

Gossett lost his seat in 2019 to Girmay Zahilay, who was a senior at Franklin High in the mid-2000s when Gossett was a guest speaker at an event to prepare students for college. Zahilay met the longtime leader, who impressed him as an advocate who seeks out community connections.

“He was what they call the conscience of the council,” Zahilay says. He had a grassroots approach and worked constantly to help his colleagues understand the impact of their actions. “When you are representing the disenfranchised, you have to govern in a different way,” says Zahilay, who occasionally calls Gossett for insights about the council and the district. Before leaving office, Gossett was working on just-cause eviction—ensuring that people can’t be evicted for no reason, especially during a pandemic or crisis, something Zahilay is carrying forward. “I’m glad I can be here to play a role in that.”

Though Gossett is no longer in office, “he’s still doing it today,” says Zahilay. Despite the pandemic, he turns out for marches and protests, including the events last summer on Capitol Hill. “He’s always there.”

Gossett’s 21-year-old granddaughter, Nea, a UW Bothell student, seems to have inherited his drive for activism. “Her name means ‘one with purpose,’ ” says Gossett. “She went to 26 of 33 demonstrations last summer.” He probably would have gone to all of them, too, but because of his age, his family was concerned for his health during the pandemic. Instead, he and Rhonda encouraged Nea’s commitment to the Black Lives Matter movement, he says, “We just said be careful.”

Today, Gossett is working on a memoir, continuing his activism and seeking new ways to serve his community. While some people who leave office take a souvenir like a chair or painting, Gossett took his county phone number. If someone needs to reach him, they still can, he says. “I’m always going to be a servant of the people.”