Srinya Sukrachan always pictured herself in the background. The recent University of Washington School of Nursing graduate never wanted to be a doctor, for example. Diagnosing does not appeal to her.

“I like being behind the scenes,” she says. “I don’t need to … have the shining star.”

Sukrachan, 26 (pictured at top), recently accepted a job at Swedish Medical Center in the antepartum ward working with women who have high-risk pregnancies. While at the UW, she founded a club for future nurses, received numerous scholarships and served as volunteer coordinator at a camp for high school kids interested in nursing, a camp that she once attended.

But it wasn’t simple.

Sukrachan is the first in her family to graduate from college and, like many first-generation students, she wasn’t sure what college might demand, she sometimes felt like an impostor and hesitated to ask for help—sometimes she didn’t even know what kind of help to seek. But her mentors at the nursing school made sure she did not give up. “I wasn’t always the one to reach out to them,” she says. “I didn’t know if they cared about me in that way.”

The first ones: Walker Flynn, left, Alberta Harvey, center, and Sara Chen navigate the culture and bureaucracies of higher education. With the help of friends, mentors and teachers, they traverse different worlds of home and school. Today one-third of incoming undergraduates are first generation.

At the UW’s Seattle campus, about 30 percent of this year’s incoming freshmen are first-generation, defined by the U.S. Department of Education as students whose parents do not have a four-year degree. At UW Bothell and UW Tacoma, first-gen students make up more than half of the population.

Nationally, first-gen students tend to come from lower-income households. They leave college without completing a degree at higher rates than students whose parents finished college.

“I’m pretty happy. I’ve lasted two years so far,” says Alberta Harvey, a member of the Yakama Nation who has her sights set on a business degree. One of the keys to surviving her freshman year was finding and bonding with other students who were having the same experiences, she says.

After tackling classes in the summer quarter, she took a break before returning to school in September. But she was raring to start her junior year. “It feels good to be back on campus,” she says. “I sort of feel like I’m home.”

For Sara Chen, the complications of being first gen started even before she got college. She had to figure out on her own how to navigate the testing and application processes. Then she had to explain to her parents, Chinese immigrants, why she had to pay fees just to apply. And then, once in school, she found her long daily commute to class from South Seattle exhausting. Fortunately, she now lives closer.

Walker Flynn, a junior from Tacoma, went through a time when he wasn’t sure he wanted to stay in school. He credits Kendrick Wilson, an academic counselor on the Office of Minority Affairs & Diversity’s Educational Opportunity Program team, with helping him find the motivation to keep working toward his American Ethnic Studies degree.

Ibette Valle, ’16, now a Ph.D. student at University of California, Santa Cruz, draws upon her own experience to inform her studies on how social environments, culture and family affect the college transition for first-generation students.

Universities are challenged to get first-gen students through some of the statistical dis- advantages they face while also building on their unique strengths, says Ibette Valle, ’16, a doctoral student in social psychology at the University of California, Santa Cruz. She studies how social, cultural and familial factors affect the college transition of first-generation students.

It is important to recognize that many first-gen students who come to college do not separate from their families and become independent, she says. Rather, they are an extension of families who rely on them to help pay bills, provide language translation and care for younger siblings.

When she arrived at the UW in 2012, Valle was the first in her family to graduate from high school. Her parents, migrant farmworkers from the state of Guerrero in Mexico, had finished their educations in elementary school.

When Valle was 16, her older brother was deported. Her parents went back to Mexico to help their son get settled while Valle stayed behind in Vancouver for her last year of high school. Alone there, she was responsible for paying bills and taking care of the family’s apartment.

Instead of seeing those commitments as burdens to overcome, Valle says, colleges should take steps to encourage the kind of family interconnectedness first-gen students often bring with them to campus. For example, Valle wanted to invite her parents for UW Parent and Family weekends, but “none of the programming would’ve been relevant to them because it was all in English.”

For the most part, Valle considers the UW’s services for students like her better than services on other campuses. The College Assistance Migrant Program in OMA&D helped her find a community, she says. She also worked at First Year Programs, where the staff was eager to hear her ideas for improving outreach to first-year students. “They wanted my feedback and they wanted to implement it right away,” Valle says.

The UW is pursuing new ways to support first-generation students, says Michaelann Jundt, associate dean of undergraduate academic affairs. Steps like offering families financial assistance to travel to campus for orientation could go a long way toward helping first-gens feel like they belong. OMA&D also provides services like tutoring and one-on-one advising for about 3,500 first-gen students of all backgrounds. The office also connects first-gen students with peers and mentors who have similar interests.

Last November, the UW participated in the national First Generation College Celebration. Embracing the notion, OMA&D handed out some 2,000 buttons campus-wide declaring, “I am first-generation.” The celebration invited faculty and staff to identify themselves as first-generation to students and offered them a chance to find others on campus—including staff and professors—who were also the first in their families to go to college.

“It sends a message to those first-gen students to look where these people ended up—that you, too, can do it,” says Rickey Hall, vice president for minority affairs and diversity and university diversity officer. Hall is also first-gen.

Danica Miller says she felt isolated as a first-gen undergraduate at Western Washington University and later as a graduate student at Fordham University in New York. Today, Miller, a member of the Puyallup Tribe, teaches American Indian Studies at UW Tacoma. “If there were things that I didn’t know—and I see this all of the time with my students—I assumed it was me,” Miller says.

To address that alienation and apprehension first-gen students sometimes experience about

their place at the University, Miller makes a point at the end of each semester to let students know she is available to review law school applications or strategize about letters of recommendation.

“For me that’s part of the sort of privilege of being a first-generation prof,” Miller says. “They just need somebody to validate that they’re amazing.”

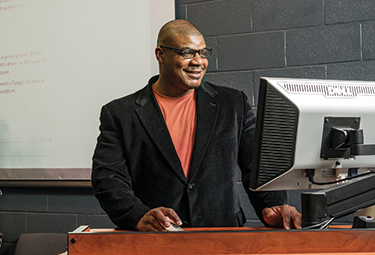

First-gens like Marcus Johnson, ’13, UW Bothell, bring a variety of identities and expectations to graduate school. Now, while navigating toward his Ph.D. in communication, he’s part of a community of leaders lighting the way for future first-gens.

Like Miller, Marcus Johnson is a first-gen who brings a variety of identities and experiences to college. Now a 39-year-old Ph.D. student in communication, Johnson thinks of himself a bridge between his family and higher education—not just as a first-generation college student, but also as a black man who grew up in Seattle’s Yesler Terrace public housing project.

He had to push past the limited expectations for those who do not fit the stereotype of college-bound students. At Cleveland High School, Johnson was assigned to special-education classes for unspecified behavioral issues. As a result, he says, when he decided to go to college, he had to teach himself algebra and calculus. He also learned on his own how to fill out a college application, all the while working and caring for his daughter and his nephews.

First-generation graduate students have an even steeper hill to climb, coping with impostor syndrome, greater financial challenges, and the complex norms and culture of graduate school.

Recognizing these things, the Graduate School has started a program to create visibility for first-generation graduate students, faculty and campus leaders. The program helps students meet other first-gens through social events and workshops, reducing the stigma of being first- gen by highlighting students’ strengths and diverse experiences.

“It’s not just about being first-gen. It’s about being a father, being a black male,” says Johnson. “There are multiple layers to my identity that I have to deal with every day when I step foot here.”