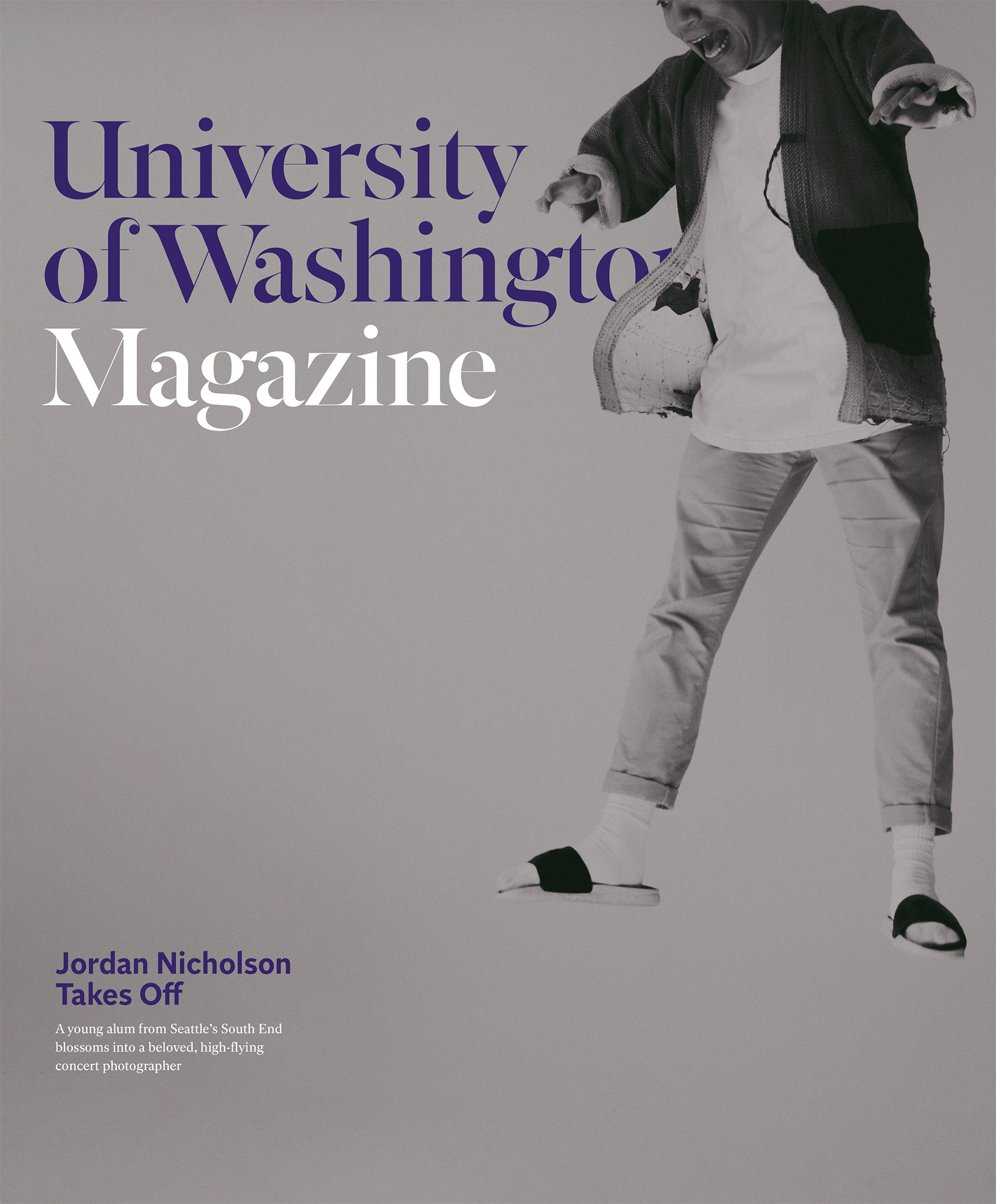

Jordan Nicholson

takes off

Jordan Nicholson

takes off

Jordan Nicholson

takes off

How the self-proclaimed lover of life followed his passions to become an accomplished photographer, artist and man about town.

By Julie Davidow | Photos by Abdi Ibrahim | September 2019

In high school, Jordan Nicholson would fall asleep at night planning his outfit for the next day. He imagined combinations of neon in all colors. A photo taken his senior year captured him with a bright pink bandana around his neck, electric green beaming from his T-shirt and eye-popping orange-and-lime laces on his sneakers. Students at Franklin High in Seattle’s South End were known for their fashion flair in the early 2000s, and Nicholson intended to stand out.

More than a decade later, walking toward me dressed in all black, the 29-year-old Nicholson could easily have gotten lost in the crowd at the corner of Broadway and Pine on Capitol Hill—except for the burst of pink at his feet. A pair of Comme des Garcons’ Nike Air Max 180s serve as a kind of street-style calling card. This is Nicholson’s neighborhood—a five-block zone of skateboard shops, streetwear stores and concrete where he honed his aesthetic as a photographer and artist and built a community of creatives.

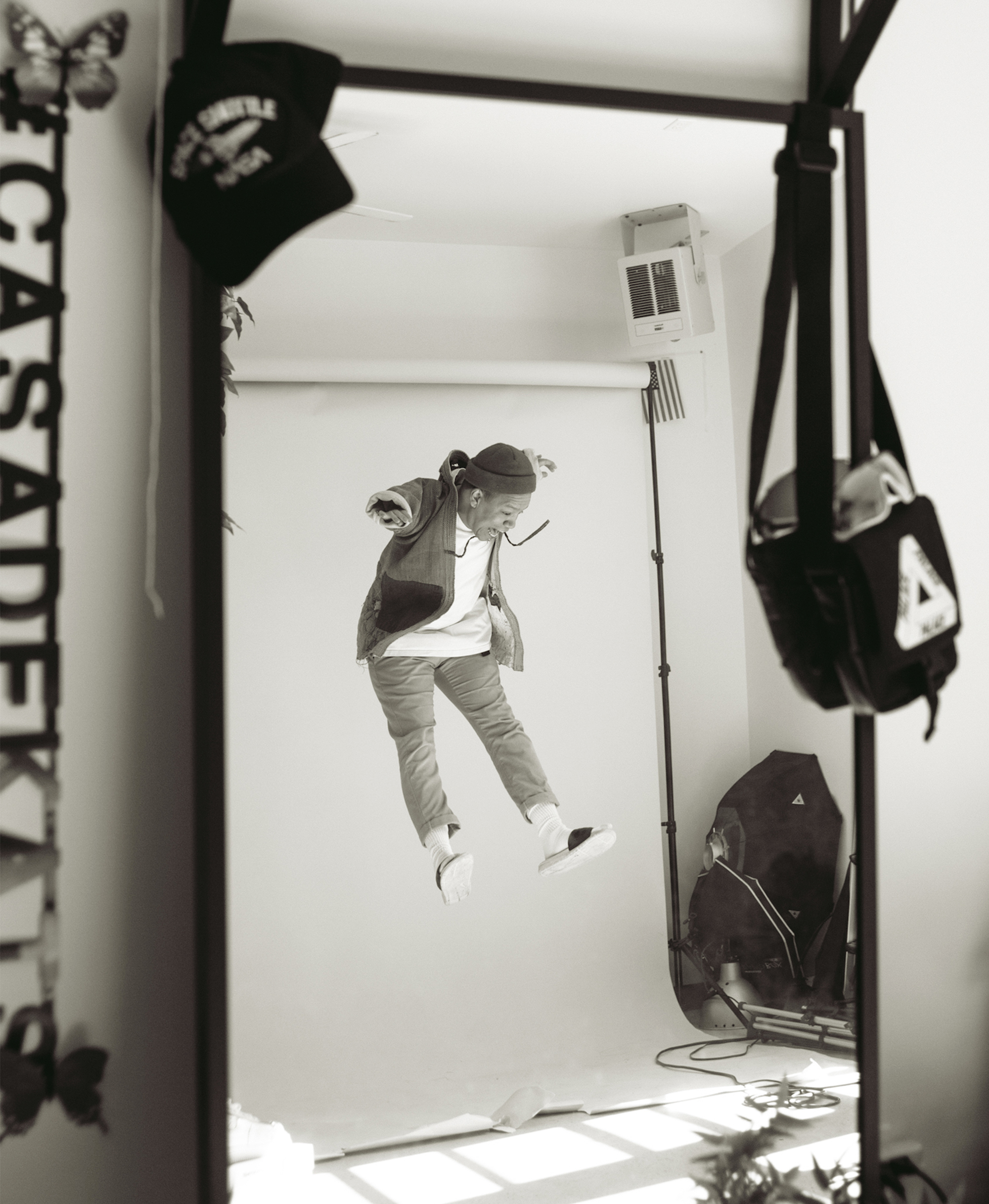

PHOTO: ABDI IBRAHIM

Nicholson, ’12, was born with TAR syndrome, a rare, genetic disorder that left him without the radius, or forearm bone, in his arms. People have always stared. They have questions. That doesn’t bother him. “I feel like it’s been the biggest advantage being such a distinct person,” he says. Another photographer might need to meet a potential client several times before they make an impression, he says. “But for me, it’s like, you meet me and within five seconds, ‘I’m always going to remember that dude.’ ” Rather than retreating and hoping they’ll look away, Nicholson invites everyone in, even this 40-something mom asking for a cool-kid tour of Capitol Hill.

No one can ever place exactly how or where they met Nicholson. It’s a running joke as we make our way down the blocks where Nicholson and his friends used to hang out after school. They’d take the bus from Franklin, skateboard down Pike Street and check out clothes and sneakers at streetwear stores that have long since closed. The broke teens often ended up at 35th North, a shop where they could find beat-up, used skateboard decks for free.

At first, the familiar faces and greetings during our walk seem too plentiful, their goodwill too generous to be spontaneous. “Hey Jordan!” a friend shouts from across the street. Did someone set this up? It becomes clear this is just Nicholson’s life. People gravitate toward him. They remember him. They want to be around him. As much as his artistic talent, this ineffable quality is the currency that carries him through the world.

We run into Eric Choi at Bait, a high-end temple to urban fashion with glossy white displays featuring $300 sneakers. Choi, who works there, met Nicholson when they were students at the UW. Or was it in the B-boy scene? “That’s the story of Jordan,” Choi says. “He attracts a lot of energy to him.”

Nicholson’s personal life, interests and art meet in ways that are difficult to pigeonhole and even more challenging to trace. There’s no linear career path, no A-to-B ascension from art major to concert photographer. He’s been drawing and taking pictures since he was a teenager. Back then he was known around Capitol Hill as the kid with the camera and a keen visual style, says Tommy Devera, whose new men’s clothing store, Estate, opened on Pike Street in April. Nicholson was an early adopter of the collaborative, DIY-ethos now setting the pace in Seattle’s streetwear scene, where art, hip hop and fashion overlap, Devera says. “Jordan was a bridge for a lot of people.”

When we walk into Estate, a 16-year-old singer from Toronto named Johnny Orlando is shopping with a friend. Orlando is performing a sold-out show at Neumos across the street that night. It’s typical for visiting musicians to make the rounds of a city’s streetwear shops, Nicholson says. Every store is different. “Just as much as it’s about the clothes, it’s also about the curation of a vibe,” he explains to me with characteristic patience for the enthusiastic, but clueless tourist in his milieu. The music, the lighting, the fixtures all work together to create a unique experience. “There’s cool products. That’s part of it,” says Nicholson, whose own sneaker collection (which he thinks of as “wearable sculptures”) numbers in the dozens of pairs. “The part that has sustained me is the communal aspect.”

Our September 2019 cover story.

That confluence of photography, streetwear and music is how Nicholson landed the job he had throughout college at Alive and Well, a now-defunct skateboard specialty store in Capitol Hill (the brand is still active). As an employee, he met other people at the intersection of his interests. The future owners of the 45th Stop N Shop & Poke Bar in Wallingford had connections to K-Pop artists and liked Alive and Well. Through them, Nicholson started taking behind-the-scenes photos of Korean musicians who came to Seattle to shoot their videos. His experience shooting concert photos for local hip hop duo Blue Scholars (DJ Sabzi, ’03, and MC Geologic, ’13) led to a connection to Macklemore. “The Heist,” Macklemore’s 2012 debut album, includes a drawing and photo by Nicholson in the album art.

His Instagram feed ranges from photos he has taken as a freelancer—sometimes for Live Nation or Setlist.fm—of Pharrell, Lizzo and Jay Park to street snaps of people he notices while traveling for jobs in Seoul, Los Angeles, New York and D.C. Each person he photographs, from celebrity to unknown, becomes part of a larger project—a journal of his life in pictures, he says. While we’re at 35th North, he pulls up a Flickr account from 2007 to show me a photo from high school of his friends lounging on a couch in front of the store’s shoe display. “When I share photos, it’s like, this is a scene from my life. I was here at this place and time,” he says. “I think that’s what drew me to photography—that ability to capture a moment in time.”

Looking through Jordan’s lens

Nicholson puts his open demeanor down to many influences, not least of which is the racial and ethnic diversity of Seattle’s South End, where he still lives in a building of live/work artist lofts on Rainier Avenue. His mother is Chinese and his father is black. At Franklin, more than half the students are Asian, 27% are black and 8.7% are Latino. White kids, at 6%, are the minority. His high school parties were filled with teens from Chinatown-International District, Beacon Hill, Kent and Tacoma. “You’d show up at this random house and it would just be like all brown kids.” Nicholson didn’t think of Asian as an undifferentiated group until he started college. “I knew that Laos is different from Cambodia, and Filipinos have their own culture,” he says. “These are things that everybody we grew up with knows. For us, there was a Seattle South End culture that was the combination of all these different cultures.”

At the UW, where 27% of the students are Asian, Nicholson realized, “Oh, yeah. I’m a minority.” When he looked for a community to join, the Filipino American Student Association felt right. “It was almost like the closest thing to what I was used to. They took me in.” Capitol Hill, the Filipino student group and Franklin have connected him in surprising and unexpected ways to music scenes and people across the Pacific Rim. The internet also played a big role in establishing and nurturing those connections. He’s made more than one friend in other cities from his days posting on online sneaker forums. “Unknowingly, in pursuing the things I like, I was just throwing out a big net to the entire world.”

Last year, the YouTube channel HiHo Kids asked Nicholson to be in a video for their series in which kids interview someone with an interesting job or life story. He was nervous at first. As much as he’s lived and shared his life online, this would be by far the largest platform (“Kids Meet a Photographer with TAR Syndrome” had logged 3.7 million views as of August). In the video, Nicholson answers questions directly and laughs easily.

Do you guys notice anything interesting about me? “You smile a lot.” “Do you have a girlfriend?” I don’t have a girlfriend. “Do you have a boyfriend?” I don’t have a boyfriend. “You have no one?” Will you be my friend? “What kind of things do you take photos of?” “Is it hard to take photos with smaller hands?” Actually, I think my arms are the perfect length to hold a camera. “Do you ever wish that you had longer arms?” “Can you do monkey bars?” I can’t do monkey bars—maybe the one thing I can’t do.

The video prompted messages from viewers all over the world. A few stick with him, including one from a person on their way to therapy. “Your video inspired me to follow my dreams and be myself. Greetings from Indonesia.” Nicholson was touched. “If I can conquer self-love and be as comfortable in my skin as I can, hopefully other people will be like, ‘If Jordan can do it, I can do it, too.’ ”

On Capitol Hill, we wrap up the afternoon at Totokaelo, a boutique where streetwear and high fashion become one. “This is what I think Kanye’s house looks like,” Nicholson says, as we descend into the men’s shop. The downstairs space is spare, with white concrete floors and white walls. Clothes, shoes and bags add all the color. Nicholson comes here to admire the items for sale as works of art, like you would at a museum. Again, familiar faces pop up. He stops to chat with a Totokaelo employee he knows from Moksha, a clothing store, art and performance space on the Ave that moved to the International District. “If you don’t know Jordan, I don’t think you’re from Seattle,” another employee says. Backlit by a wall of sneakers lined up on wooden shelves, Nicholson slips into the third person, turning the interview into an opportunity to see himself through someone else’s eyes. “Why do people connect with you, Jordan?” The answer, he proposes, is simple. “Being yourself is powerful.”