Keeping with tradition Keeping with tradition Keeping with tradition

The UW was made, in part, by alumni like you. 120 years ago, students bonded over labor and improved the UW campus.

By Caitlin Klask | Photos courtesy of UW Libraries Special Collections | September 2024

Picture this: You’re a student at the UW in 1904. When you look around the University District (then known as Brooklyn), you see trees, trees and more trees. No light rail, no crowds, no cars. Construction for the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, which cleared some of the wilderness and brought temporary structures to the area, won’t begin for several years. Campus consisted of just a few structures: a science building, a power plant, a women’s dorm, a men’s dorm, Denny Hall (then the administration building) and a gymnasium.

“When I first saw it, I thought it was a train-shed,” Henry Landes wrote about the gymnasium in the 1916 Tyee Yearbook, four years after becoming dean of the College of Science. Born and raised in Indiana, Landes was “absorbingly interested” in the newness of Seattle and the winding, primitive trails across campus.

“The President, returning home one night from some function, fell over a cow that had grown weary at nightfall and had made her downy couch athwart the trail to [his] house,” he wrote. “The embarrassment was mutual.”

Edmond Meany, class of 1885 and 1889, was a history professor with a vision for the future of higher education in Washington. As a naturalist, he dreamed of preserving those trees and turning campus into an arboretum. But as a pragmatist, he dreamed of a bustling campus to rival East Coast elite schools. He secured 355 acres to expand the UW’s footprint, and then he implemented Campus Day to improve the campus.

- Lunchtime looked kind of like that scene in ‘Midsommar,’ but only men ate at the tables while women served them, which might be as bad as that scene in ‘Midsommar.’ Photo credit: University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, UW6137

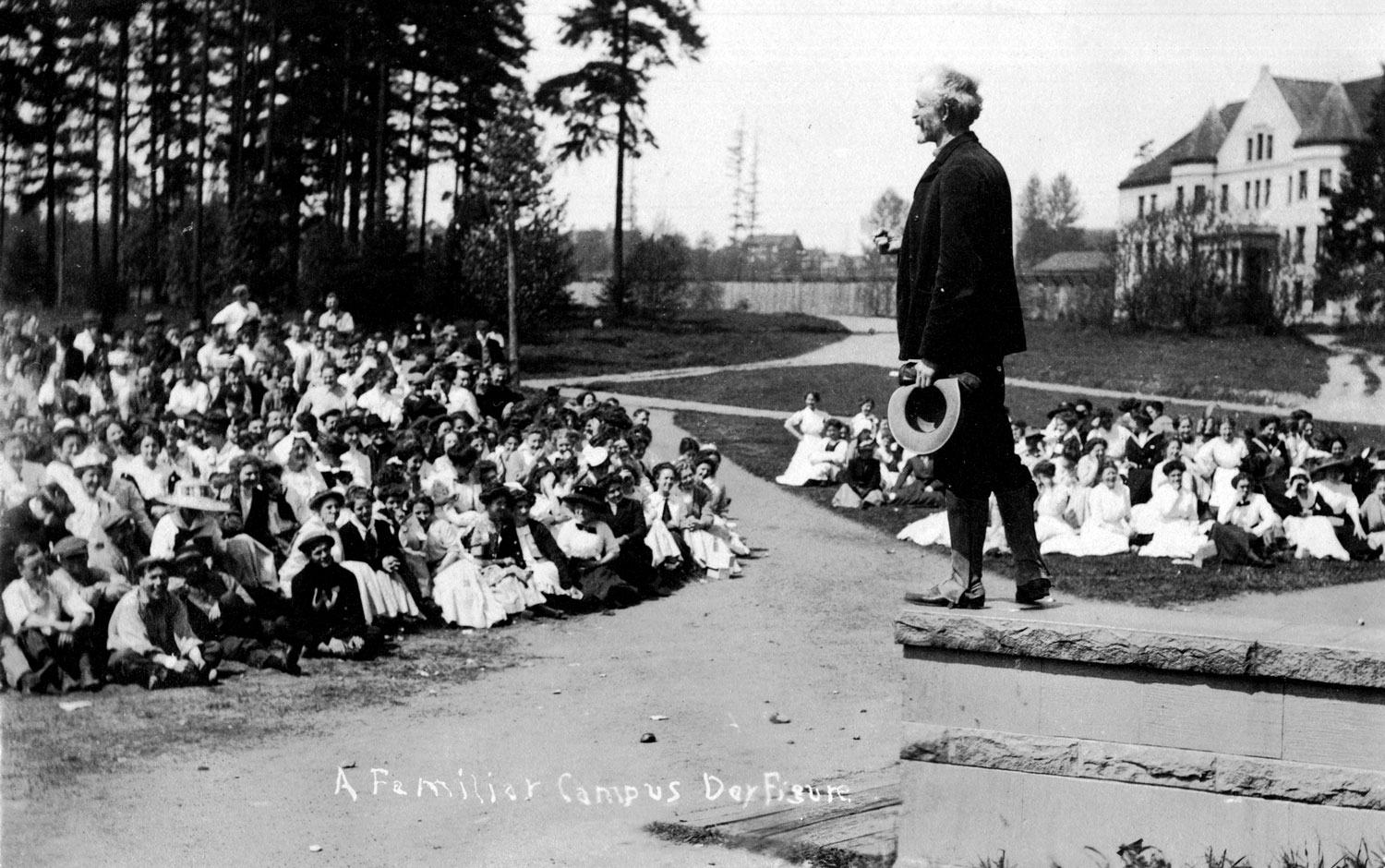

- A photo of Edmond Meany addressing a crowd reads ‘A familiar Campus Day figure.’ One might think these students would harbor a grudge for the man who made them work all day, but all records show the opposite: They loved Meany. Photo credit: University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, UWC5258.

Campus Day—where students and faculty stepped away from their studies to get outside and work—occurred every May from 1904 until 1934. If you were a woman, you’d find yourself plucking dandelions, preparing food and carting buckets of water to your fellow sweaty male students or patching up their wounds. And if you were a man, you’d be chopping trees, carting refuse or even raising the Columns on Denny Lawn in 1911.

Antoinette Wills, ’75, historian and retired UW staff member, explained that manual labor was not out of the ordinary for students in the early 1900s. “The rich men sent their sons to Yale,” she says. “UW tuition was free at the time. It was a real case of ‘if you build it, they will come.’”

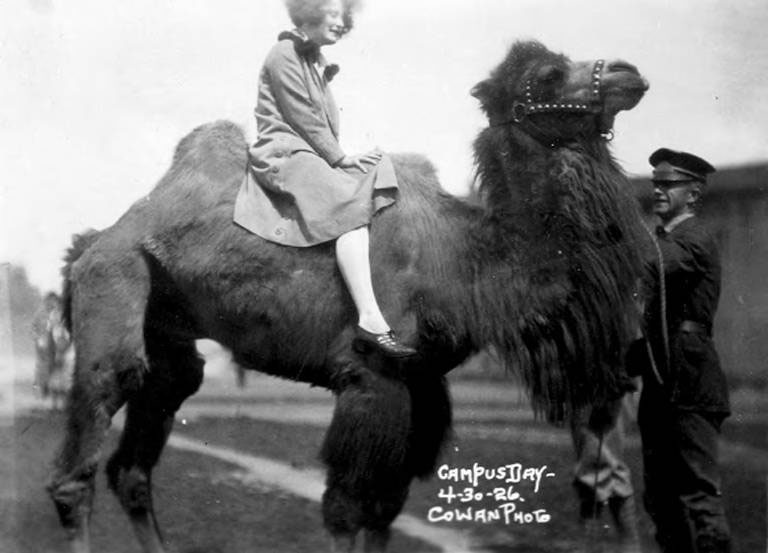

After a day of hard work, students and faculty would gather for a meal. There were speeches, choral performances, faculty-vs.-students baseball games—some pictures show women going for a “Campus Day ride” on a camel. Students, likely glad to have a day off from studying, gave Meany a round of applause everywhere he went.

A student rides a camel on Campus Day 98 years ago. Why? We don’t know. Photo credit: University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, UWC3582.

When Meany’s mother sent him a newspaper clipping about “Labor Day” at a California university, it inspired him to give it a try at the UW. After all, Meany, a historian, was “consumed by a burning zeal for Washington,” Landes wrote.

Edmond Meany demonstrates proper scythe usage (perhaps) to a laboring student. Photo credit: Asahel Curtis Photo Company, 6215.

Meany might not have predicted the “frosh pond” tradition coinciding with Campus Day, but as soon as Geyser Basin (which we know now as Drumheller Fountain) was installed in 1909, sophomores began dunking freshmen in the pond.

But that rite of passage faded away, as would Campus Day, which ended in 1934. Meany proposed concluding the event, seizing an opportunity to provide well-paying jobs to gardeners and laborers during the Great Depression. He died the following year.

The professor was affectionately known as “General Meany” during Campus Day, but students were so thrilled to be part of the UW’s legacy they competed to see who could get the most work done. In 1914, students and alumni raised money to present Meany with a new car as a “glowing tribute to his service.”

The place, according to Meany, was imbued with a pioneer spirit. “It’s what the West promised,” says Wills. “Opportunity.”