Since 2010, students have savored the lessons of Dr. Chocolate. The UW Bothell lecturer, also known as Kristy Leissle, is a leading researcher of the global cocoa trade.

“Chocolate is socially meaningful in a way that most other foods aren’t,” Leissle says over a cup of hot cocoa in University Village. “It has whole movies and books about it, and even the word itself sparks our desires. If I say ‘vanilla’ or ‘peach,’ it doesn’t do that.”

Leissle will spend the spring finishing her new book, “Cocoa,” which traces the history, politics and economics of the global chocolate industry. It’s part of a series called Resources by UK publisher Polity Books. Other authors have tackled timber, oil, diamonds and even body parts.

Cocoa powder, which is used to produce chocolate, is made by grinding up cacao beans harvested from oval-shaped pods that grow on trees. Indigenous to Central and South America, the crop has been popular as both a bean and a drink for over 3,000 years.

Demand surged in Europe after colonizers developed a taste for it, and people from Africa were enslaved to harvest the crop in the Americas. “There’s a darker side to this thing that makes us so happy,” Leissle says. Europeans eventually transplanted the tree to sub-Saharan Africa, and nowadays around three-quarters of the world’s cocoa comes from that region, mainly Ivory Coast and Ghana.

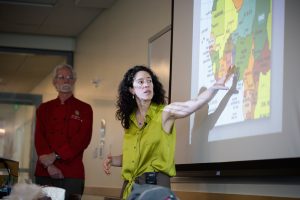

Kristy Leissle maps out the cocoa trade as Chocolatier Bill Fredericks looks on.

Leissle did her doctoral fieldwork in Ghana as a student in UW’s Department of Gender, Women & Sexuality Studies (GWSS). The idea for a dissertation about chocolate came after she earned a Bonderman Fellowship, an eight-month study abroad opportunity for UW students to explore topics outside of their degree. Leissle went on a global tour of chocolate—her first love—that took her from Southeast Asia to Europe. “I want to be traveling like a cocoa bean travels,” she said in her Bonderman interview.

When she got back from her trip, her faculty advisor, ethnographer Priti Ramamurthy, encouraged her to further her chocolate studies. “A Ph.D. is a very long and lonely process,” says Ramamurthy, a GWSS professor. “You have to be passionate about about what you’re researching.”

Leissle drew up a dissertation that looked at the gendering of the cocoa trade. In Ghana, she saw a male-dominated industry, but in Britain, she found advertisements displaying African women as farmers. “This crop is highly gendered,” she says, “and as it transforms from cocoa to chocolate, the gendering of it switches.” She finished her Ph.D. in 2008. As far as she knows, she’s the first person to get a doctorate by studying the cocoa trade.

In addition to the cocoa trade, Leissle researches the craft chocolate industry. She shares her findings in academic journals, industry magazines and her own “ChocoBlog.” From 2010 to 2013, she worked as the educational director of the Northwest Chocolate Festival. That’s where she got her nickname, “Dr. Chocolate,” courtesy of chocolatier Steve DeVries, a founder of the American craft chocolate movement.

“She’s not just analyzing chocolate from an academic perspective,” says UW Bothell colleague Ben Gardner. “She’s engaged in public conversations with industry folks, and she’s connected to communities of people for whom chocolate is a central thing.”

Photo: Dan Bates

A handful of companies dominate the global market: Mars, Nestlé, Hershey, Mondelez (Cadbury), Fererro (Nutella, and gold-foiled Rocher balls) and Meiji (in Japan). But in the past 15 years, hundreds of craft chocolatiers have sprung up and transformed the industry. They work with high-quality beans, tailoring their flavors to the bean itself rather than a brand. Craft chocolate only makes up a small percentage of the market, but it’s changing the way we eat, buy and talk about chocolate.

Leissle appreciates the fine flavors of the craft world, but she hasn’t sworn off mainstream chocolate. It’s partly nostalgia: As a child on Long Island, she cherished Hershey’s Kisses and hoarded Special Dark bars. It’s also a matter of money. Chocolate is a $12 billion industry that employs five million farmers, and millions more people depend on the cocoa trade for a living. “They struggle and they suffer,” Leissle says, “but they have an income and a market.”

She admits the big companies can improve their practices—but she doesn’t think a boycott is the answer. The major problems that farmers face, such as unreliable water supplies and a lack of paved roads, need to come from a corporate tax base in a country, she says, not the cocoa industry itself.

So what can a conscious consumer do? Support trade justice movements and buy certain brands if you agree with the company’s practices or prefer their product. But don’t buy into the notion that one category of purchase can save the world. Instead, Leissle says, think bigger. “What do I think helps? Learning. Reading. Teaching. Voting. Our global and civic engagement has to change.”