2 fatal shootings leave trail of grief at UW

During the lazy, warm summer days of early July, a sobering sight could be seen at the University of Washington: flags flying at half-staff.

It was a gesture of mourning and shock at a tragedy that rocked the campus a week earlier. On Wednesday, June 28, Jian Chen, a second-year pathology resident, distraught at being terminated, walked into the private UW Medical Center office of his mentor, Pathology Professor Rodger Haggitt. Chen locked the door behind him. A discussion turned into yelling and shouting. Then, five shots rang out. Chen had fatally shot Haggitt, a world-renowned gastrointestinal pathologist, four times. Then he turned the gun on himself.

Trying to come to grips with this tragedy was difficult enough. But it was not the only killing to hit the campus community this year. Exactly two months earlier, James Hunter Sanderson, a happy-go-lucky freshman from Bellingham, was shot and killed just before midnight after he walked across the hood of a pizza delivery driver’s car in the University District.

Friends say the 19-year-old Sanderson was under the influence of LSD (toxicology reports have not come back yet), which could explain his behavior that night. Sanderson was yelling and hugging strangers on the street as he walked along the Ave. But witnesses’ accounts vary when they describe the shooting. Some told police Sanderson opened the car door and tried to grab the driver, who defended himself by shooting Sanderson in the neck. Others say Sanderson got off the car hood and was walking away when the driver yelled at him, causing Sanderson to turn. The driver then pulled out a handgun and shot him. (The 22-year-old driver, who had been robbed before, had a concealed weapons permit.) As Columns went to press, the King County Prosecutor’s Office had not yet decided whether to charge the driver, whose identity is protected unless he is charged with a crime.

While unrelated, the two fatal incidents left many in the campus community wondering: was this the start of a trend? Have the University of Washington and the University District become dangerous places? Or were these incidents just awful aberrations?

“It was a fluke, just happenstance,” says Joe Weis, a UW sociology professor who is an expert on crime and teaches a class on murder. “There is no connection at all. There’s nothing you can read into these beyond the incidents themselves.”

What makes these two tragedies stand out is how rare they are, and that they both occurred so close to each other in time and distance. In all of 1999, there were just two murders in the Seattle Police Department’s North Precinct—all of Seattle north of the Ship Canal, including the University District. The killing of faculty is even more rare. It was the first time a UW faculty member had been killed on campus and the only time a shooting had ever occurred at the UW Medical Center.

“It is highly unusual to have a shooting at a hospital, especially here,” adds Weis, whose daughter works in the medical center. “At a university, we’re supposed to be more civilized. You will always find crime rates much higher in a downtown or other urban areas than in a university.”

The last known incident of a faculty member being killed on a U.S. college campus occurred in 1996, when a graduate engineering student at San Diego State University, agitated because his master’s thesis was failing, shot and killed three faculty members during a routine meeting to defend his work.

“The UW campus is actually a quite safe place,” notes Vicky Peltzer, the chief of the UW Police Department. While the campus does have crime problems, most center around property crimes such as theft and car prowling. The last murder on campus occurred in 1990, when Azizolla Mazooni of Iran, was convicted of shooting his 18-year-old girlfriend, Marjan Mohseninia, and a male friend of hers, Ebrahim Sharif-Kashani, in front of Denny Hall. He told police he shot her in a jealous rage after tracking her down with the help of a private detective.

“The biggest element to crime on campus comes from outsiders,” Peltzer says. “It’s like any university when it is in a big urban center. Transients, runaway children and other people with no funding source or place to live usually cause the problems. It’s highly unusual for this type of incident to happen here.”

A recent survey by the Chronicle of Higher Education showed disturbing increases in the number of alcohol and drug arrests and in violent crimes at the nation’s colleges, but the UW’s statistics placed it in the middle of the pack compared to its academic brethren. For example, in 1998, the UW (enrollment 35,367) reported 221 liquor law violations, 72 drug violations and six weapons arrests. Washington State University, with a much smaller enrollment (20,243) reported 355 liquor law violations and 88 drug offenses, the survey shows. Other major urban schools with similar enrollments reported much higher numbers than the UW. The University of Wisconsin (792 alcohol arrests), Cal-Berkeley (280 drug offenses) and Michigan State University (49 weapons arrests) all reported much higher numbers than the UW.

As for workplace violence, it is incredibly rare on college campuses, but academic medical centers (the UW has two, UW Medical Center and Harborview) could be seen at risk. The Washington Department of Labor and Industries conducted a 1999 survey and found that health care employees face the highest rate of workplace violence in the state of Washington. Weis explains that this is significant because most episodes of violence in the workplace are not really related to work. “It is usually someone with a personal problem, taking it to work,” he says. “An estranged spouse comes looking for his partner where she works. It isn’t often that the violence is related to the workplace.”

Jian Chen

But at the medical center the problem was work performance. Chen, 42, came to the University of Washington after two years at a residency program at the University of Mississippi. Prior to his arrival, he was a promising scientist, but he began to struggle in one of the nation’s most renowned and demanding pathology programs. He became angry and difficult as he was told his work was subpar, and engaged in shouting matches with his supervisors. When his supervisors recommended he consider moving to another program or undergo psychological counseling, he grew more upset.

Some pathology colleagues were so scared by Chen that they started locking their doors when he was around. “There was considerable concern and consternation on the part of the department faculty,” says John Coombs, associate vice president for medical affairs and associate dean of the medical school. “And there was fear as well.”

That increased when department officials learned that Chen was shopping for a gun. Medical residents saw yellow pages turned to gun shops, and even spotted a map to a gun shop on his computer screen. At a meeting in late May, he was asked by department officials and police if he was going to buy a gun, and he said he wanted one for protection. Officials warned Chen that it was illegal to carry a gun on the UW campus. Because Chen—who had no criminal record—never made a threat against any specific individual, there was nothing more law enforcement or University officials could do. A UW policeman even saw Chen at a Bellevue gun shop but didn’t report it until after the shooting.

Two weeks before his final work day, Chen’s background check was complete and he was cleared to pick up a .357 Glock semi-automatic pistol, which he had purchased for $479. Chen meticulously planned his suicide—he prepared letters to be sent after his death, including one to Haggitt, whom he apparently did not intend to kill. It is possible that Chen changed his mind and decided to kill Haggitt, or perhaps Haggitt tried to intercede and stop Chen’s suicide. The medical examiner’s report was inconclusive and we will never know what went on behind those locked doors.

Rodger Haggitt

Haggitt, 57, a Seattle resident, was a world renowned gastrointestinal pathologist who helped develop many methods for treating gastrointestinal cancer and disease. A native of Detroit, he spent most of his life in Tennessee, went to medical school at the University of Tennessee, and joined the UW in 1984. Here, the man who loved blues and firing up the barbecue helped establish ways of treating gastroesophageal reflux disease. He also was credited with coming up with the protocol for biopsies in many transplant centers. “It’s going to be a terrible blow to us, almost irreplaceable,” said Pathology Professor George Martin. Haggitt was survived by his wife and three grown children.

A native of Shanghai, China, Chen had become a naturalized U.S. citizen and had published articles in scientific journals and made presentations at national conferences. He had gotten along well with people at schools he studied at in China, New York, Iowa, Texas and Mississippi. But after he arrived at the UW, he began to struggle. His command of English was less than fluent, and that created problems. So did his stubbornness. Former colleagues say he felt humiliated when his ideas were rejected or deemed too impractical. And when he was told his contract at the UW would not be renewed, he felt even more humiliated. The result was shocking—and deadly.

Sanderson’s death was likewise as shocking—but isolated. University District crime is a problem, but by far the vast majority of it is considered nuisance crime—shoplifting, graffiti, aggressive panhandling, blocking sidewalks. “There is no evidence at all that this is a trend,” says Janine Brackett, executive director of the Greater University Chamber of Commerce. “We keep our finger on the pulse of the district, but there have not been any concerns that we have a real safety problem here. This was a sad, terrible but isolated incident.”

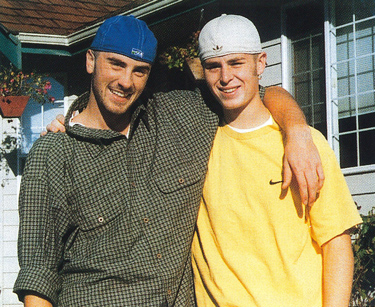

James Sanderson

Nonetheless, Sanderson’s death devastated many of the 98 people who lived on his floor in his dorm, Lander Hall. Sanderson was an outgoing, exuberant kid who was not the least bit intimidated about leaving home for the first time to come to a huge, metropolitan university. When he moved into the dorm, he went around introducing himself to anyone he could find. When his floor—called Frosh House, a “specialty” coed floor to help freshmen adjust to college life—had a sign-up sheet for a new event, Sanderson was always the first to add his John Hancock.

His door was always open. He asked everyone how their day was going. When someone was depressed, he would tell him, “Only 76 days until winter break!” He was the one who would roust people out of bed, help make apple pancakes for breakfast and get everyone pumped to see the Apple Cup game at Husky Stadium.

A lanky kid who wore his cap backward, he often went around shirtless to show off his gecko tattoos. With his hair dyed hi-lighter yellow, Sanderson was loved by everyone. Even when he would get busted for playing his music too loud, “It was really hard to get mad at him,” says Gwen Gyldenege, an RA on his floor.

“He never hurt anyone,” says his father, Gerald Sanderson of Bellingham. He tells the story of his son’s high school basketball coach, who said Sanderson would have been a star had he possessed a mean streak. Sanderson, who as a high schooler counseled sixth-graders, mowed lawns for the elderly, and was a member of Young Life, a nondenominational Christian ministry, could never pull the trigger while hunting. He couldn’t even pour salt on slugs.

“He valued life too much,” says his father. “We instilled in kids that people are good. Maybe he was a little naïve. He wasn’t afraid.

“What he did was stupid. I lay awake nights thinking why did things go wrong. He knew what we thought of drugs. Still, he didn’t deserve the ‘sentence’ he got.”

Every year, a handful of UW students die in accidents or suicides. “But what makes this a hard one to believe is that not many college kids get killed,” explains Professor Weis. “College students don’t usually get themselves in situations that are likely to lead to lethal consequences.”

James H. Sanderson (left), with friend Jim Higgins, stands in front of Sanderson’s home in Bellingham. The UW student was one of the most popular freshmen living in Lander Hall. Photo courtesy Gerald Sanderson.

But this incident brought together what Weis calls two of the most volatile choices that can lead to death—drugs and guns. (The third is alcohol.) And while LSD has made a comeback lately, G. Alan Marlatt, a UW psychology professor who is an expert in the field of drug abuse, says that the UW is much lower than the national average when it comes to drug and alcohol use on college campuses.

While a decision has not been made to press charges against the man who shot Sanderson, the debate continues whether the situation was a matter of self-defense. “What mattered is that a threat was created,” explains John Junker, a UW law professor specializing in criminal law and self-defense issues. “If the person using force believed he needed it to defend himself, and it was reasonable, then it is not a crime. You do not have to submit to be unlawfully attacked. If the driver believed he was being attacked, he could use force.”

One thread common to both shootings is that they involved handguns purchased legally. Gun control advocates say that the availability of handguns makes these type of firearm deaths possible. Deaths from firearms in the United States tower above those from any other Western country, they say. Advocates for the possession of guns maintain that people must be able to defend themselves, as in the case of the pizza delivery driver who had been robbed before, and that the medical center murder-suicide, while tragic, should not keep law-abiding citizens from their constitutional right to bear arms.

Are there lessons to be learned from these two tragedies? The UW Police Department is making prevention of workplace violence a priority, and security at UW Medical Center will be increased, especially because of the trend of violence against health care workers. More training and the creation of crisis assessment teams will help give UW officials a way to try to keep on top of these potentially volatile situations. “We have a lot of work to do,” says Peltzer, the UW police chief. “It is a real wakeup call.”

But there is only so much anyone can do, especially when fatal choices are made. We can wonder: what if Sanderson had not experimented with LSD or if the pizza driver had not carried a gun? What if Chen hadn’t reacted so adversely to his situation or if Haggitt had asked others to attend that fatal meeting?

“The real story here is that these were two tragedies,” says Weis, the crime expert. “It’s so rare and shocking to have killings like these happen in your community. But it isn’t a trend.”

Editor’s Note: On Sept. 18, the King County Prosecutor’s Office decided not to file charges against the pizza delivery driver involved in the shooting of James Sanderson. Also, on Jan 3, 2001, the state Department of Labor and Industries ruled that the UW did not break state regulations on workplace violence in events leading up to the shooting of Dr. Rodger Haggit.

Memorials offered

To make a contribution to the James Hunter Sanderson Memorial Scholarship Fund (for UW-bound students), send a contribution to: Meridian Public School Foundation, 214 N. Commercial Street, Bellingham, WA 98225. For more information, call (360) 676-0507.

To make a donation to the Rodger C. Haggitt Memorial Fund, send a contribution made out to: “UW Foundation” to UW Department of Pathology, Box 357470, Seattle, WA 98195-7470.