60 years after prosecuting Nazis at Nuremberg, Whitney Harris is ready to revisit the past

Sixty years ago, Whitney Harris sat down in a room with the captured Nazi war criminal Rudolf Hoess. The most extraordinary thing about the Auschwitz commandant, Harris recalls, was how ordinary he seemed—small, polite, unprepossessing. “You wouldn’t think of Rudolf Hoess as a mass killer,” Harris says. “No, you wouldn’t.”

Sixty years ago, Whitney Harris sat down in a room with the captured Nazi war criminal Rudolf Hoess. The most extraordinary thing about the Auschwitz commandant, Harris recalls, was how ordinary he seemed—small, polite, unprepossessing. “You wouldn’t think of Rudolf Hoess as a mass killer,” Harris says. “No, you wouldn’t.”

Yet over the course of three days in Harris’ company, Hoess confessed to the murder of, by his own estimate, 3 million people. In 1941, he had been ordered to convert Auschwitz from a concentration camp to an extermination center. “He did so to the best of his ability,” Harris wrote in his 1954 book “Tyranny on Trial: The Evidence at Nuremberg,” now in its third edition, “and his ability was such that he became the greatest killer of history.”

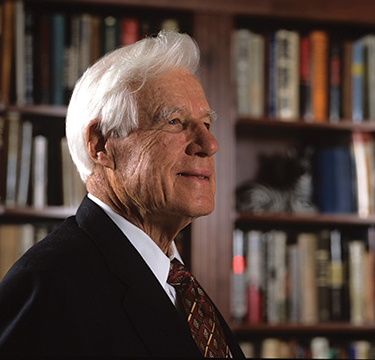

Harris, ’33, is one of only two surviving prosecutors from the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal, and the only one who was present for the entirety of the historic trials. His job was to make the case against Ernst Kaltenbrunner, head of the SS intelligence service and the Gestapo, and he made it decisively; Kaltenbrunner was the only Nuremberg defendant who didn’t appeal his death sentence. Harris received the Legion of Merit for his services.

Now 94, Harris still talks about the trials with impressive subtlety and specificity. He remains proud of the precedent Nuremberg set—the first international war crimes court in history, it was a model of fairness and transparency, he says. It also established an authoritative record of Nazi crimes against humanity.

“That will stand in history,” Harris says, “because it was subjected to every possible challenge and criticism at the time the facts were developed.”

Harris was born in Seattle in 1912 and matriculated to the UW, where he pledged Phi Kappa Psi and studied sociology. He graduated magna cum laude in 1933, took his J.D. from Cal-Berkeley three years later, and practiced law in Los Angeles until the start of World War II, when he joined the Navy. Toward the end of the war, Harris was transferred to the Office of Strategic Services and put in charge of investigating war crimes in Europe. It was in that role that he impressed the staff of Supreme Court Justice Robert H. Jackson, the U.S. chief counsel at Nuremberg. They soon recruited him to the prosecution team. He was only 33 at the time.

After the trials, Harris joined the law faculty of Southern Methodist University and wrote “Tyranny on Trial.” “I said to myself, ‘Listen, we’ve got to get these facts on record so that nobody’s going to be able to rewrite this history!’”

Following its publication, he turned his attention co his family and work—and away from Nuremberg. Devoting most of a decade to thinking, talking and writing about inhumanity, he realized, had taken its toll. “I really cast it out of my thoughts,” he says.

Harris enjoyed a distinguished career in corporate and private practice. He also made his mark philanthropically, most notably at Washington University in St. Louis, which recently renamed its Institute for Global Legal Studies in Harris’ honor.

It wasn’t until the semicentennial of the Nuremberg judgment, when he began receiving invitations to speak about the trials, that Harris realized he would be comfortable doing so. He’ll revisit the subject once more on the weekend of September 29-October 1, when scholars and dignitaries gather at the Harris Institute to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the verdicts.

“It’s the passage of time that has made it bearable,” he says.