When Jon Jory was growing up in Pasadena, Calif., his father went to work each morning and came home in the evening to his wife and two children. It was a middle-class existence not much different from the one that thousands of other children experienced in the 1940s—except that Victor Jory’s work involved acting in dozens of movies, his wife (Jean Innes) was also an actress, and both Jon and his sister got Actors’ Equity cards at about the same time most kids are getting their first report cards.

So it’s not surprising that Jon Jory grew up to be a theater director, nor that when he talks about theater, his vocabulary has more to do with work than with art.

“I’ve always been sort of hostile to the word ‘artist,’ “ he muses. “I don’t know what it is. I think of myself as a theater worker. I think there probably are such things as artists and I think in my field there may be as many as four or five in a generation. The fact that everybody else trots about calling themselves artists I find somewhat amusing.”

“Worker” would be an accurate description of what Jory has been since coming to teach at the UW School of Drama in the fall of 2000. He teaches several classes a week—both graduate and undergraduate—attends faculty meetings and has directed a play. A bearded, gray-haired man in his early 60s, he can be seen sitting among his students wearing jeans and a comfortable sweater, and he constantly solicits their ideas about acting and directing.

But despite denying any claim to artistry, Jory is an extraordinary catch for the drama school. He spent 31 years running Actors Theatre of Louisville, which he brought from obscurity to national prominence. While there he nurtured dozens of new plays, several of which went on to win the Pulitzer Prize (The Gin Game, Crimes of the Heart and Dinner with Friends), and he has been inducted into the Theater Hall of Fame. Nonetheless he will tell you stubbornly that during his time in Louisville, he “got up in the morning and went to work in the American theater.” No cape, no beret, no exotic accent, just a man doing his job.

“It would never have occurred to me to think about medical school or law or any of those other things, simply because in our family we worked in the theater or film or TV or radio.”

Jon Jory

He comes by that attitude naturally. His parents started their careers in “42-week stock,” a form of theater in which the actor appeared in 42 plays in 42 weeks. This was in the early part of the 20th century, when training programs were rare and actors learned their craft by watching their more experienced colleagues. The elder Jorys went on to act in films, with Victor landing leading-man parts until he was typecast as a villain, most notably as Jonas Wilkerson, the scheming overseer in Gone With the Wind, and Injun Joe in The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. By the time Jon was old enough to remember, Victor had become a contract player in B movies, which were churned out in 20 days.

Nor was the work ethic put aside in the summer. Instead of carefree vacations, the Jory family would often do summer stock theater, with all four performing in the plays. Looking back, Jon Jory compares himself to any son who is raised with the expectation that he will enter the family business. “I don’t think the world was exactly opened up as a set of options,” he says. “It would never have occurred to me to think about medical school or law or any of those other things, simply because in our family we worked in the theater or film or TV or radio.”

When it came time for college, Jory tried to follow his sister (Jean Jory Anderson) to the UW but was turned down (“My high school career was checkered,” he says). He attended the University of Utah, did a stint in the Army and then attended Yale, but never actually earned a degree. Characteristically, he quit to go to work—as co-founder (with Harlan Kleinman) of the Long Wharf Theatre in New Haven.

It was 1965, the beginning of a new era in theater, when what came to be known as regional theater proved that not all the talent in the country was centered in New York City. The Tyrone Guthrie Theatre had been founded in Minneapolis in 1963, adding the cachet of a big name to the efforts already under way in cities like Houston and San Francisco. Jory was in the thick of it at Long Wharf, helping to mount a 1965-66 season that played to 85 percent of capacity.

But success was short-lived. Competition with a newly revived Yale Theatre under Robert Brustein brought financial problems to Long Wharf, and Jory was ultimately fired.

“That experience colored the direction his career took and how he approached the theater,” says Alexander Speer, Jory’s partner at Actors Theatre. “Jon was the artistic director at Long Wharf; his co-founder was the business manager. But the board fired Jon because of a fiscal problem. So when he came to Louisville, Jon became very interested in the fiscal end of the operation, and for that reason he was a marvel to work with. He wanted to know how each show was doing, whether departments were over or under budget, everything.”

“He felt more at home with comedy and lighter entertainment; classics were rare in his first seasons.”

Author Joseph Wesley Zeigler

Speer was the business manager at Actors Theatre when Jory arrived in 1969. “He reported to the board and I reported to him,” is how Speer describes the situation. But over time, the two worked so closely together that their relationship became an equal one; Jory always refers to Speer as his partner.

Both men were barely out of their 20s at the time, running a theater that had been in existence for five years and had only recently seen the departure of its founder. The Actors Theatre company was performing in a converted railroad station that seated 350 and Louisville was a relatively conservative city without a large theater following.

Jory’s hiring signaled the beginning of a new era for Actors Theatre. In his definitive book on regional theater, Joseph Wesley Zeigler describes Jory as “much more of a showman” than his predecessor. “He felt more at home with comedy and lighter entertainment; classics were rare in his first seasons, which were leavened by such old-time crowd-pleasers as Tobacco Road, Charley’s Aunt, Our Town and even Angel Street.”

Furthermore Zeigler writes, Jory was “much more of a huckster” too. He describes the director’s efforts to do industrial shows during the theater’s “dark” months, as well as his offbeat promotional campaigns.

By 1972 the company had moved to new quarters housing both a 637-seat main theater and a 159-seat arena space named the Victor Jory Theatre in honor of Jory’s father, who performed at Actors Theatre annually. The audience had grown from a few hundred subscribers to 9,000. But the theater was still, in Speer’s words, “a small theater in a small city, not well known outside of Louisville.”

That changed when the board asked the two to write a long-range plan and they tried to think of what would put the theater on the map. “Jon knew it was hard for new playwrights to get a start, so it was his idea to sponsor a new play festival,” Speer says.

“Jon is about as unpretentious as anyone I’ve ever worked with. Everything is about, ‘How do we make this work?’ And he has a really good sense of humor.”

Richard Dresser, playwright

That festival, initiated in 1976, was an instant success and has launched the careers of many playwrights. Richard Dresser, for example, has had five plays (Alone at the Beach, Below the Belt, Gun Shy, What Are You Afraid Of? and Wonderful World) produced at the festival, and calls Jory “a very important person in my life.”

Dresser credits Jory with helping him polish his scripts without imposing his own ideas. “When we talked about it, I never felt like anything was coming down from on high,” Dresser says. “In fact, Jon is about as unpretentious as anyone I’ve ever worked with. Everything is about, ‘How do we make this work?’ And he has a really good sense of humor.”

The Humana Festival—as it is known because of its corporate sponsorship—developed into the leading new play festival in the country, its productions reviewed in the New York Times. Three of those productions—The Gin Game (1978), Crimes of the Heart (1981) and Dinner with Friends (1998)—won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama.

That success is emblematic of the prominence Actors Theatre had achieved by the ‘90s, but Jory was beginning to think about moving on. His daughter Jessica was considering college, and the pair visited the UW, where Drama Professor Robyn Hunt picked them up at the airport and showed them around.

Near the end of the visit, Hunt asked Jessica to do a monologue for her. “When she finished,” Hunt remembers, “Jon said, ‘Now Robyn, would you like to show me a monologue?’”

Hunt complied and a few months later Jory called her, asking if she would like to come to Louisville to play Lady Capulet in a production of Romeo and Juliet. It was the first of several roles Hunt did there, and it was also the beginning of an ongoing relationship between Jory and the UW School of Drama, which his daughter did choose to attend (she graduates this month). Jory visited and gave a workshop for the Professional Actor Training Program.

Soon after, the effort to bring Jory to the UW began.

“He’s a born teacher. He has tremendous energy, and he tries to bring out the best in each student.”

Robyn Hunt, drama professor

Of his decision to leave Actors Theatre, Jory has this to say: “If you work on a car engine for a long period of time, you really don’t know how to tune it any better than you’ve tuned it. And you really don’t understand, I think, after a certain point what’s possible outside a structure that you’ve developed. So I sort of felt that way about the theater. I couldn’t see any further into the engine so it was a matter of repeating, which didn’t seem wildly entertaining.

“Plus, I’d devoted a lot of time to an institution; I was tired of being a boss. I don’t know how good that is for you spiritually to be a boss for a very long time. I think it’s more fun to build something than to sustain it. I’d very much enjoyed building it. I wasn’t as entertained by sustaining it.”

The School of Drama is thrilled to have him. “He’s a born teacher,” Hunt says. “He has tremendous energy, and he tries to bring out the best in each student.”

His administrative experience is valued as well. Drama School Director Sarah Nash Gates recalls a staff meeting during which a perennial scheduling problem was being discussed. “Jon asked these wonderful questions, always pretending to be naïve, and he helped us see where we were doing things a certain way because we’ve always done them that way. He told me afterward, ‘An organization should always have somebody new to go to lunch with.’ “

In his office in Hutchinson Hall, Jory has mounted photographs of his parents on the walls—many of his father in costume for various movie roles. Occupying a prominent position is a photo of both parents as they appeared in an Actors Theatre production of Long Day’s Journey into Night, which he directed. Jory has clearly not forgotten where he came from or all the practical things he learned at the feet of working actors and directors.

These days, however, actors and directors are formally trained and there are fewer veterans around to pass on wisdom. So Jory has written a book, called Tips for Actors, that consists of short pieces of practical, how-to advice on everything from conquering self-consciousness to gracefully handling being fired. He has another book, Tips for Directors, due this spring.

But the lucky students in the School of Drama don’t have to read the books. Jory brings his lifetime of experience into the classroom. “I think in training young people it’s a combination of experience and theory,” he says. “I bring more experience than theory. My value is that I can shortcut problems. I can tell you something that you will learn anyway in 10 years but do you have to wait 10 years to learn it? That, I think, is the most valuable gift I have to offer. I can just cut some time off the process.”—Nancy Wick, ‘97, is editor of University Week, the UW faculty/staff newspaper.

The mystery of Jane Martin

When Jon Jory founded Louisville’s Festival of New American Plays (now the Humana Festival of New American Plays) in 1976, he was already a playwright himself, having written the dialogue and lyrics for three musicals. But Jory’s greatest success as a playwright may have come under a pseudonym. He is reputed to be the mysterious “Jane Martin,” who is the most-produced playwright of the festival, with 10 full-length plays performed there between 1982 and 2001. Martin has also written six one-acts and a number of shorter plays that have been seen on the Actors Theatre stage and elsewhere.

When Jon Jory founded Louisville’s Festival of New American Plays (now the Humana Festival of New American Plays) in 1976, he was already a playwright himself, having written the dialogue and lyrics for three musicals. But Jory’s greatest success as a playwright may have come under a pseudonym. He is reputed to be the mysterious “Jane Martin,” who is the most-produced playwright of the festival, with 10 full-length plays performed there between 1982 and 2001. Martin has also written six one-acts and a number of shorter plays that have been seen on the Actors Theatre stage and elsewhere.

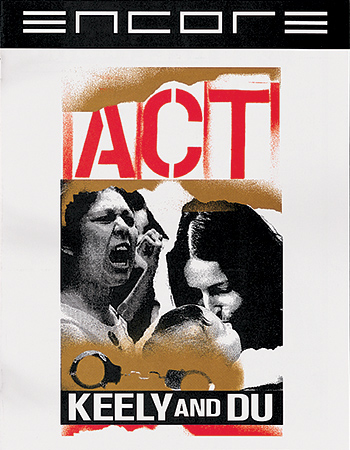

If Jory is indeed Martin, he may be using the pseudonym to explore his feminine side. Two of the full-length plays (Talking With and Vital Signs) are essentially a series of monologues by female characters, while others (Keely and Du and Mr. Bundy) explore issues (abortion and child molestation, respectively) of particular interest to women. This has led some critics to speculate that Jory is collaborating with his wife, Marcia Dixcy Jory, on the Martin plays.

But Martin isn’t strictly a “woman’s playwright.” His/her entry in the 2000 new play festival was Anton in Show Business, a comedy about a third-rate theater company doing a production of Chekhov’s Three Sisters. The New York Times described the play as skewering every element of the business: “Self-involved actors, autocratic directors, romantic and uninformed producers, complacent audiences, presumptuous critics, cynical corporate sponsors all get their comeuppance here#&151;even Actors’ Equity, the union, one character says, that makes sure ‘no more than 80 percent of our membership is out of work on any given day.’ “

Anton in Show Business is one of four Martin plays that have been honored by the American Theater Critics Association (Talking With, Jack and Jill and Keely and Du are the others), but in each case Martin did not appear to receive the award. Keely and Du was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, and it’s anybody’s guess whether the author would have dropped his/her cover if the award had been conferred.

For now, Jory simply isn’t talking. He will not admit to being Martin, and will offer no commentary on the plays. When asked about it, he says only, “I’m not going to talk about that.”

The secret is in the text

Despite Jon Jory’s practical, handed-down-for-generations approach to the theater, he is a big fan of textual analysis. He describes his work as grounded in action theory, a system that breaks drama down into action—what the character wants; tactics—how the character goes about getting it; and obstacles—what is preventing the character from getting it.

In a Jory class, students will be asked to analyze text and decide what their action and tactics are at any given moment. Then he’ll question them about it as they perform a scene.

“He always knows what he wants out of a given scene,” says Drama Professor Robyn Hunt, who has performed in Jory-directed plays. “But he gives you room to get to that result in your own way. He builds a structure in which you can work.”

Jory does not believe that textual analysis should be confined to the director. “Very often actors in the American theater have been seen as simply embodying craft waiting for the magic of the director’s ideas,” he says. “I prefer a situation in which the ideas are moving back and forth. I assume the more ideas there are in the rehearsal room, the greater the opportunity to find a set of good ideas that will function with that particular piece of material.”

Though he’s open to actors’ ideas, Jory can still be a taskmaster. Hunt reports that he once called a rehearsal for 9 a.m. on New Year’s Day. “And he was there on time, raring to go.”