He wanted to be standing in the sunshine with the other seniors, listening to his coach praise his five years on the Husky football team. He yearned to feel the butterflies as he prepared to meet the cross-state rivals in the final home game of the season. He wanted to be thinking about simple things: making a big hit, graduating in June or even his NFL prospects.

Instead he was 500 miles away, confined to a wheelchair, just a voice on a loudspeaker. But Curtis Williams was still part of the University of Washington football team.

In a pre-game speech, Williams urged his teammates, especially the seniors, to go out and defend their home turf against a favored Cougar squad in the 2001 Apple Cup. He told them to play their best, not just for themselves, but for past, present and future Huskies.

“You could hear a pin drop when he spoke,” said Football Coach Rick Neuheisel. “That was the first time he ever asked us to win one for him.”

Curtis Williams photographed in his brother’s home in Clovis, California, on Jan. 31, 2002. Photo by Paul Mullins.

But, Neuheisel added, the Huskies’ dominating 26-14 victory on Nov. 17 was much more than just a win for Curtis. That the injured 23-year-old football player could speak more than a few words without being interrupted by a ventilator—that Curtis could speak at all—was a huge victory. It’s these small steps in overcoming terrible odds that make Curtis Williams a hero to every teammate, coach, family member, friend and fan who has tried to deal with what happened on Oct. 28, 2000, when the Husky defensive back became a quadriplegic.

It was a cold, soggy day in Palo Alto, Calif. The Huskies were entrenched in a close battle with Stanford in a key Pac-10 game. As he had all season, Williams played an excellent game at strong safety. He led the defense, tallying a game-high nine tackles through less than three quarters of play. Then, in a flash, one play, one tackle, forever changed Williams’ life and the lives of those around him.

Husky Safety Greg Carothers, at the time a true freshman defensive back, remembers the play vividly. He was on the sideline, perpendicular to Williams’ spot on the field. Instead of watching the ball, as he usually did, Carothers focused on Williams.

As the play developed, Williams identified a handoff and charged forward to plug a running lane, making a play he had made a hundred times before. Simultaneously the ball carrier, Stanford running back Kerry Carter, powered through the line of scrimmage toward Williams. The players collided at full speed, helmet-to-helmet. Both players fell down. Only Carter got up.

“After the hit, you could tell that something was wrong, the way his body went,” Carothers said.

Quarterback Marques Tuiasosopo (11) holds hands with teammates before the 2000 UW-Arizona game as they pray for injured teammate Curtis Williams. Photo by Steve Ringman, copyright 2000 Seattle Times.

In the midst of the driving rain and the muddy Stanford Stadium turf, Williams lay motionless. Defensive tackle Larry Tripplett, then a junior, also watched from the sideline. He too felt that something was terribly wrong.

“Knowing Curtis, knowing how tough he is, you kind of expected him to get up,” Tripplett said. “And when he didn’t get up right away, I think everyone on the team started to get nervous.”

“We felt a significant concern before we even reached Curtis on the field,” said Husky Trainer Dave Burton, the first to attend to Williams on the field that day.

As Burton approached, his worst fears were confirmed: Williams was unable to speak and had trouble breathing. Burton tried to comfort and reassure him.

“He was conscious but he was visibly frightened,” Burton said. “You could see the expression in his face.”

Burton continued talking to Williams as an assistant held his head in place. The Stanford response crew called an ambulance, and trainers hooked Williams up to an emergency-breathing device. What seemed like an eternity actually lasted only eight minutes, Burton said, and the Stanford response crew’s quick action saved Williams’ life as he was rushed to the Stanford University Medical Center. His condition stabilized and doctors placed him on a ventilator.

Williams had sustained damage to the first and second vertebrae at the base of his skull—the most serious non-lethal spinal injury one can suffer—leaving him paralyzed from the neck down. Not only was his dream of playing professional football over; his life was in jeopardy.

***

It wasn’t supposed to end like this. The Fresno, Calif., native, nicknamed “C-Dub,” was becoming a great football player. Bill Stewart, his high school coach, always knew he had great potential. “He was extremely mature for his age,” Stewart said. “I was very impressed by his high confidence level. He had a good head on his shoulders.”

Off the field, Williams was very humble and a little quiet, Stewart said, but on the field “he played loud.” At Fresno’s Bullard High School, Williams displayed his considerable talents as a running back and a cornerback. He was one of the most highly touted running backs on the West Coast, having rushed for more than 1,400 yards and 31 touchdowns as a senior. Most colleges wanted him as a runner but Stewart recalled his prowess on the other side of the ball.

“Oh yeah, he would bring the lumber to you,” Stewart said, describing the 5-foot-10, 200-pound Williams’ hitting ability.

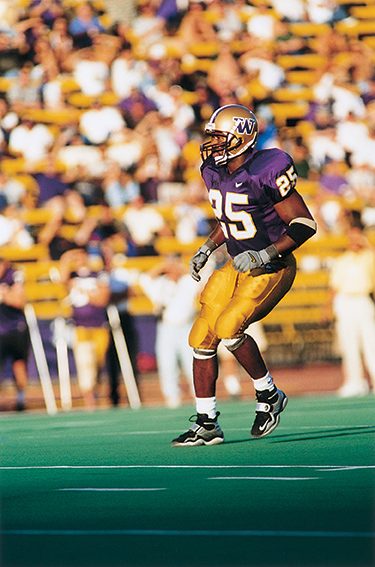

Curtis Williams became known as a hard-hitting safety as a Husky.

In high school, Williams appeared to be headed for success on the field, but he had made some mistakes off the field. At age 16 Williams fathered a child, Kymberly, with his then-girlfriend Michelle. He eventually married Michelle but the couple later separated. Around that time, Donnie Williams, Curtis’ father, suffered a heart attack, so older brother David Williams stepped in to look out for his brother. Curtis lived with David and his family in Fresno for his final two years in high school.

The two brothers always had an extremely close bond.

“He was my little buddy,” David said, recalling his football days when he brought game balls home to young Curtis.

They even played the same position (running back) in high school and David watched his little brother chase many of his rushing records. With a 14-year gap in ages, he became more like a father to Curtis than a brother. Under his guidance, Curtis stayed on track and completed an excellent senior season, eventually accepting a football scholarship to the UW.

Under Coach Jim Lambright, Williams saw limited playing time, buried on the running back depth chart. His first three seasons (including one redshirt) were frustrating, he said. But everything changed when Rick Neuheisel and his staff took over in 1999. They immediately recognized Williams’ ability—they had tried to recruit him at Colorado. However, the staff didn’t see him making the most impact at running back so they asked him to switch to defense as a free safety.

Curtis just wanted to play, so he jumped at the chance. According to Bobby Hauck, the UW’s safeties and special teams coach, Williams learned the position quickly. Playing first as a free safety, he became known as a big hitter, always lurking and ready to paste any opposing players who ventured into his sights.

Williams also excelled on special teams and soon became a defensive leader. He finished the 1999 season with 69 tackles and a new outlook on football. The California native was emerging as one of the Pac-10’s best defensive backs, a superb athlete realizing his physical potential.

***

But all of that ended on a rain-soaked field in Palo Alto. Following his initial treatment at the Stanford Medical Center, Williams spent four months in a rehabilitation unit at the Santa Clara (Calif.) Valley Medical Center. As soon as he was ready to be discharged, he left to live with his brother David and family.

David took an extended leave from his job as a full-time manager at a medical waste facility to learn how to take care of Curtis. The hospital staff taught him how to adjust and clean the ventilator, how to treat his skin, how to clean Curtis’ bowels and how to move him safely. Many of Curtis’ family members, who have always made family their priority, helped to take care of him. Curtis says he gained a new appreciation for their love.

“It makes me realize just how much family means,” he said.

For several months the family was responsible for taking care of Curtis 96 hours each week due to an insurance problem. Williams is covered under the NCAA’s catastrophic injury insurance policy. The policy, which provides up to $20 million in lifetime benefits, originally had a $100,000 limit for in-home care. A change last August bumped that up to $250,000. (His disability insurance also provides child support for Kymberly, now 7.) Now Williams receives 120 hours of skilled in-home care each week, easing the load on the family.

Williams also appreciates his other family: the multitude of Husky fans and friends from around the country who have sent him thousands of notes of encouragement. He still receives letters every week.

“I want to thank them for their overwhelming support. And to let them know that I’m movin’ on.”

Curtis Williams

“I want to thank them for their overwhelming support,” he said. “And to let them know that I’m movin’ on.”

More than 2,000 fans have contributed to the Curtis Williams Fund, set up in November 2000 to cover the substantial costs outside of insurance. The fund has garnered close to $400,000. Holding a pen in his teeth, Williams signs thank-you notes for donors.

Last June he underwent unconventional surgery to wean him from the ventilator that had helped him breathe since the injury. Doctors implanted a phrenic nerve pacemaker under the skin near Williams’ collarbone. The pacemaker electrically stimulates the nerve, which stimulates Williams’ diaphragm, a muscle that aids breathing.

Before the surgery, Williams was only able to speak in short, rough bursts when his ventilator pushed enough air into his lungs. Actor Christopher Reeve, who suffered a similar spinal injury, speaks in this manner. But Williams now spends all of his waking hours off of his bulky ventilator. The pacemaker allows him more mobility and improved speech. With the aid of a speech therapist, Williams has vastly improved his speaking ability.

Although Williams is confined to his electric wheelchair, which he controls with his chin, he still has friends over and goes out to movies. He loves to talk about football and he frequently receives calls and visits from former teammates and coaches.

Williams saw his teammates in person for the first time since the accident at the January 2001 Rose Bowl in Pasadena. He was named as the team’s fourth captain and watched from the press box as the Huskies saluted him by raising their helmets just before kickoff. The Huskies went on to beat Purdue 34-24, and some players dedicated the win to their fallen teammate. “We all knew we had to do one thing,” Fullback Pat Conniff said. “We knew we had to play our guts out for the guy. The guy is battling it every single day. The least we could do was go out and battle it out for four hours.”

Since then, Williams has attended the Huskies’ game at UCLA last October and the Dawgs’ Holiday Bowl game in San Diego. He hopes one day to return to Husky Stadium for a home game, but medical transportation costs make that extremely expensive.

***

Experiencing emotions ranging from anger to sadness to acceptance, Williams says he still has tough moments every day, but he has never given up. This spring he plans to finish some of the final 30 credits needed to complete his bachelor’s degree from the UW in American ethnic studies. His speech improvement is vital, as he will use a voice-activated computer to take UW distance-learning courses.

“I figure now (my education) is most important, since I can’t rely on my body anymore,” he said.

Williams realizes that his situation is likely permanent. His current focus is on doing whatever he can to make the most of his new life and to be a good father to Kymberly, who has been visiting more frequently. To better accommodate Curtis, the family recently moved to a new home 13 miles northeast of Fresno. The Curtis Williams Fund will be used to improve Williams’ quality of life there, David said. The property will be renovated to include larger doors for Williams to pass through in his wheelchair and he will now have his own room.

“He can still be a young kid,” David said. “He’ll have his own space and some privacy.”

David also plans to set up an automated workout room for Curtis. In the event that medical technology can someday repair his spine, Williams must maintain muscle tone to meet the physical demands of walking. Due to lack of use, his muscles have significantly deteriorated, but automated workout machines would force his muscles to move and stay relatively toned, David said. Curtis’ once-rippling muscles on his 5-foot-10 frame are gone, but Williams’ impressive determination keeps him constantly pushing forward.

Despite all that football has taken away from him, Williams is not bitter. In fact, his goal is to stay involved in the sport any way he can, either by coaching high school kids or scouting—possibly for the Huskies. If given the choice, the one-time running back would coach defense.

“It’s where I ended,” he said.

Neuheisel, normally very tongue-in-cheek with the media, becomes quite serious when he talks about Curtis. He frequently keeps in touch with his former star, and he often looks at the picture of Williams that sits in his office as a reminder of his enduring strength.

“He’s a remarkable person,” Neuheisel said. “The way he presents himself is stirring. “As difficult as this has been—and I can only imagine how truly difficult it has been—he never lets on. He’s clearly one of my heroes.”

High-tech program teaches disabled to just DO-IT

As former Husky football player Curtis Williams strives to earn the final 30 credits he needs to complete his bachelor’s degree at the UW, two roadblocks stand in his way. First, he will continue speech therapy to become more comfortable with his phrenic nerve pacemaker. Second, he needs practice with his voice-activated computer before he can take correspondence courses from his brother’s home in Clovis, Calif., where he lives.

Fortunately, when these issues are resolved, the UW’s nationally recognized Disabilities, Opportunities, Internetworking and Technology (DO-IT) program will be ready to help.

Developed by the College of Engineering and the Office of Computing and Communications in 1992, the program links disabled high school and college students with mentors and a wide range of technological resources in hopes of preparing them for college and future career opportunities. The program, which currently serves several hundred high school and college students, won a 1997 U.S. presidential award for excellence in science, mathematics and engineering mentoring. Also, last October the UW received a $3.5 million federal grant to establish a National Center on Accessible Information Technology (to be known as AccessIT), which will incorporate DO-IT’s resources with the UW’s Center for Technology and Disability Studies.

Program Director Sheryl Burgstahler and her staff teach students far more than academic skills. They attempt to reverse years of learned dependency, which Burgstahler says may be the most difficult lesson of all. “We constantly say, ‘Don’t be passive.’ We encourage them to take charge of their lives,” she says.

Passivity, all too common among the disabled, will only hinder these young students in college and beyond, she says, so DO-IT pushes them to be confident and articulate, yet respectful. She tells students, “Don’t allow the attendants to do everything, especially things that you know you can do yourself.”

First funded by a National Science Foundation grant and more recently by the state of Washington and the U.S. Department of Education, the program is divided into three, yearlong phases that allow students to develop projects, work with mentors and eventually help out as DO-IT interns. Each July, 20 prospective college students arrive to take part in phase one of the program.

The 11-day summer camp includes workshops, field trips and social gatherings to prepare disabled students for college life. Campers live in a residence hall, eat lunch together on campus and even play Nintendo together.

The learning starts right away, as the students interact via the Internet before camp. As early as the first lunch, Burgstahler can see some students make important realizations.

“The kids with the non-physical disabilities are used to hiding it. They are sometimes overwhelmed when they meet everyone else that’s here,” she says, referring to the wide variety of disabilities represented at the camp. “But as they accept the other kids, they learn more about themselves and they’re forced to be open about their disability.”

The DO-IT camp isn’t that different from other summer camps, as students are exposed to a new setting that prepares them for future success. The obvious difference, Burgstahler says, is that these kids are disabled, but the more subtle difference is that they must also overcome a social gap and the handicap of dependency.

Young disabled kids don’t have many role models, Burgstahler says. “We’re trying to make this generation of kids more successful.” With its emphasis on technology and social strength, this award-winning program continues to help more and more kids DO-IT.