From the west, it looks like it could be the latest building in the University of Washington's central campus: a warm reddish-orange exterior, subdued classical design, elegant lines.

Approach that same building from the east and it looks more like its immediate neighbors: shimmering glass, burnished metal, a chillier modern mood.

Such is the dual nature of the William H. Foege Building, named after the UW School of Medicine graduate and epidemiologist who helped eradicate smallpox.

At first, the Foege Building seemed to have divided goals. The building needed to bridge the gap between the red-brick buildings of upper campus and the steel-and-glass structures along Portage Bay. It needed to accommodate the rapidly growing Department of Genome Sciences, but also provide a unified home for the Department of Bioengineering, which was scattered across nine different locations around the campus. And it had to be a facility for both the fundamental, such as basic research on the human genome, and the practical, such as development of biomedical technology.

But the final structure has one common theme running throughout: community. Both halves of the building feature communal gathering areas for faculty, staff and students. Coffee lounges and kitchen areas, open stairwells and informal lobbies with armchairs, side tables and whiteboards—all of these are meant to spur conversations between scientists, engineers and physicians.

Looking down from the railing at the top of the towering, four-story, open-air atrium in the genome sciences wing, it’s easy to imagine a young researcher calling out to a professor down on the main Boor, hoping to share some new finding with a more experienced colleague.

“The design here revolves around collaboration,” says Peter Stazicker of Los Angeles-based CO Architects, the firm that designed the Foege Building. “It’s important to have those chance meetings between scientists. We wanted places in the building to encourage that kind of interaction.”

Strong collaborations and serendipitous conversations have helped fuel great advances in the life sciences. Decades ago, in a chance meeting on the stairs of the UW Health Sciences Center, a physician told his colleague, Professor Belding Scribner, about an incredible new material—Teflon. Scribner and bioengineer Wayne Quinton, ’58, decided to use the nonstick substance to make the shunt for the first practical kidney dialysis treatment in the world.

The future residents of the Foege Building are no strangers to teamwork, either. The UW genome sciences faculty includes three of the chief architects of the Human Genome Project-Philip Green, Maynard Olson and Department Chair Robert Waterston.

Almost a half century ago, a UW bioengineer refined the medical ultrasound machine so that it gave high-resolution, crystal-dear, real-time images. Now, Yongmin Kim, the chair of bioengineering, is partnering with engineers and physicians to develop the next generation of medical ultrasound.

Bringing together the two disparate groups of researchers may also help them reach across disciplinary boundaries and partner with one another. “One tough area in biology is technology development,” says Waterston. “To have bioengineering next door, that could help stimulate us and foster collaboration.”

Where could those collaborations lead in the future? The possibilities are endless. Nanometer-sized machines could treat diseased cells from the inside out, without hurting the rest of a patient’s body. Replacement tissue or organs may soon be grown in a lab, created especially for an individual using his or her genetic profile. Doctors may one day have portable, inexpensive genome sequencing machines in their own offices or clinics, where they could warn patients about their genetic risk for certain diseases.

If such incredible discoveries could get their start anywhere, it would be in the state-of-the-art labs housed in the Foege Building. Inside those walls are some of the most advanced lab spaces in the world. One genome sciences lab has a confocal laser scanning microscope, which allows researchers to watch in real time, at incredible resolution, as living cells replicate and divide.

The 260,000-square-foot facility had a price tag of $150 million, making it the single most expensive building on the UW campus and also one of the largest. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation provided $60 million for the construction, with additional support coming from the Whitaker Foundation, David C. Auth, the Washington Research Foundation, federal research funding, the government of Singapore and other donors. Surprisingly, no state capital funds were used in the project.

Though the Foege Building was a huge construction project, the architects saved money and sped up the work by using reddish-orange tiles to cover the structure’s north and west sides. These terra cotta tiles were assembled off-site into large panels, which create a rain-screen system when fixed to the building. Based on a centuries-old European home-building concept, the tiles shield the true wall underneath them from the elements. The air cavity between the two layers also insulates the building. The final effect is much more visually appealing as well—the Foege Building shines in comparison to the drab concrete of the nearby Health Sciences Center.

Though the design of the Foege Building was tailored to the needs of the scientists and engineers who will call it home, the facility was also created with the entire University community and the public in mind. Inside the building is a “public street” that winds from the far north end, on Pacific Street, to the extreme south end, on Boat Street, allowing someone to walk the entire length of the building in publicly accessible areas.

The south side of the building presents another challenge—how do you take a massive, multistory structure and extend it to the edge of Boat Street without having it tower over passing pedestrians? The solution—break down the mass of the building before it gets to the bottom of the hill. The main floors of the building stop short of its south end. Only the lower floors, the large auditorium in particular, extend all the way to Boat Street, the light cream stone walls tapering to a dull point just before the sidewalk.

Viewed from Boat Street, the stone structure protrudes from the rest of the building, pointing like a ship’s prow at the waters of Portage Bay. The effect is subtle, though perhaps intentional—the Foege Building acting as a vessel of scientific discovery, guided by scientists and engineers who are eager to chart new courses in biology and medicine, unlocking the secrets to human development and finding cures to debilitating and life-threatening diseases.

Building honors alumnus who helped conquer smallpox

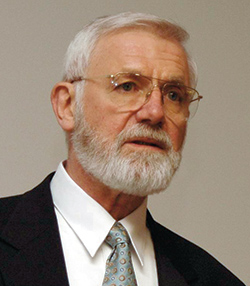

William H. Foege

When William H. Foege, ’61, went to a remote area of eastern Nigeria to give disease vaccinations, a local village chief offered to get the word out to everyone nearby. Come vaccination day, Foege was surprised by the crowd that had gathered in the tiny village, and he asked the chief why so many had turned out to get a painful needle jab in their arm.

Because, the chief told the towering public health doctor, I told everyone to come to my village to see the tallest man in the world.

Foege, who stands well over six feet tall but is far from the world’s tallest man, has spent his professional life trying to eradicate diseases and reduce health-care inequality. Foege is best known as a leader of the campaign to eradicate smallpox, which by the late 1960s still affected more than 10 million people per year in Africa, South Asia and South America. He devised a new system of vaccination that helped banish a major infectious disease for the first time in human history. He has also worked to eliminate or control river blindness, Guinea worm disease, polio and measles.

After his undergraduate education at Pacific Lutheran University, Foege received his medical degree from the University of Washington in 1961, and then a master’s in public health from Harvard. He served as a medical missionary in Nigeria, and then chief of the Centers for Disease Control’s Smallpox Eradication Program. He became director of the CDC in 1977, during the administration of President Jimmy Carter. He later went on to the Carter Center, the former president’s nonprofit organization, where he served in many capacities, including executive director.

Foege joined the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation in 1999 as a senior medical adviser to the organization’s Global Health Program. He now is a senior fellow there.