One of the University of Washington's most celebrated law graduates may turn out to be a man who never practiced law. Solely because Takuji Yamashita, '02, was born in Japan, the highest powers of the state barred him from the Bar.

This injustice took place nearly a century ago, but the personal crusade it set off, forgotten for decades, is being rediscovered by historians and civil-rights scholars who find in the UW graduate’s life epic daring and resourcefulness. Hollywood would pitch it as a courtroom drama pitting institutionalized racism against immigrant pluck—a sort of prequel to Snow Falling on Cedars. Hollywood would have it right.

This heroic new light on a forgotten alumnus comes while the law school is marking a string of centennials, from its opening in 1899 to first commencement in 1901. For a climax, Dean Roland Hjorth has asked the current state Supreme Court to publicly correct its predecessor’s misdeed (as best it can, since Yamashita has been dead for 41 years) and admit the Class of ’02 graduate as an honorary member of the Bar. Court scholars say this would be its first-ever posthumous admission, and the yet-to-be-scheduled restoration ceremony could draw diplomats, relatives and community leaders from both sides of the Pacific.

Back in 1900, Yamashita stood out as only the second Japanese student in the UW’s four decades of existence—Jinta Yamaguchi, Class of 1899, was the first—but Yamashita soon became better known as the star of the new law school’s moot court.

“Even if others do not act like true human beings, I shall act as a human being.”

Takuji Yamashita

He’d had all of six years in America to learn the ropes. He’d been recruited by pioneering Tacoma restaurateur Kyuhachi Nishii as an 18-year-old whiz kid from Nishii’s hometown of Yawatahama. The hamlet on Japan’s smallest major island, Shikoku, was about as far off the beaten track as were the muddy cities ringing Puget Sound. A merchant’s second son, Yamashita could never inherit property, but even firstborns were bailing out of a Japan undergoing a turbulent transition from a feudal economy. Before boarding the ship to America, the star graduate of Yawatahama Secondary and Uwajima Merinken schools left his parents a note explaining the journey was not for selfish desires but to bring honor on them and “work for the public good.”

“Even if others do not act like true human beings,” Yamashita promised, “I shall act as a human being.”

America treated him like a human being, at first. The talented youth sped through Tacoma High in half the normal four years—earning mediocre grades only in spelling—while living at the Tacoma Baptist Mission and waiting tables at Nishii’s restaurant on Pacific Avenue.

The townsfolk had mixed feelings about people who looked like Yamashita. All the West Coast ports competed fiercely, just as they do now, for Japanese trade. But agitators ranted about the threat to U.S. jobs and society from railroad and sawmill workers streaming in from Asia. In the Pierce County town of Sumner, a few weeks after Yamashita started law school, a mob of whites fired shots at an unarmed group of Japanese hop pickers.

From the 1903 Tyee yearbook, founding dean of the UW School of Law John Thomas Condon, who received an undergraduate degree from UW in 1879.

The year-old UW School of Law, by contrast, seemed a bastion of opportunity. It opened its doors on the eve of the 20th century, as University President Frank Graves wrote, “simply to better the opportunities of the young people of the state.” The fledgling law school offered to train any qualified man or woman able to come up with the $25 annual tuition. Classes, until 1903, were held near the downtown courts and law offices, a convenience for the practicing lawyers whom founding Dean John Condon often called upon to teach. Though the UW archives yield no pronouncements from Condon on ethnic diversity, the Tyee yearbook approvingly noted the “very cosmopolitan character” of his student population: a black man from Barbados, three women and the Japanese Yamashita alongside “native sons, Germans, Irishmen.” What Condon did state, in a speech that foreshadows today’s inclusiveness lingo, was that “equality assumes that each can try to do his best, and since the best varies with each individual, political equality should be regarded as a means of permitting these valuable personal inequalities to make their contribution.”

Yamashita’s contribution, especially in the moot court, was described in a year-end school wrap-up as “commendable.” Just as he had in high school, Yamashita sailed through Condon’s rigorous, two-year law curriculum—a program becoming known as hopeless to anyone looking for easy “snap” courses.

For all his academic finesse, Yamashita must have had moments of desolation. Classmates would have seen in his Asian background something, at best, unfamiliar. “A mosaic strange to Occidental eyes” is how a student newspaper reporter described the neighborhood where Yamashita lived while attending the UW, known today as the International District. On these streets, the writer breathlessly found, “a fat Chinaman with his pigtail hanging down” mingled with opium addicts and gamblers. When UW law students were asked to pick a personal yearbook epigram, Yamashita chose “Amicus Alienus” (Friendly Foreigner) and “Stranger in a Strange Land.”

Yamashita poses in a traditional Japanese robe for this photo, probably taken just before he left for America. Photo courtesy of the Takuji Yamashita Photograph Collection, University of Washington Libraries.

But he was on the way to becoming an American. He had to, since Washington required its lawyers to be citizens. Four days before receiving his law degree, he picked up his naturalization papers from the Pierce County Superior Court. The following week, Yamashita rode the train to Olympia with eight classmates to take what in those days was the oral bar exam. He passed with a performance The Seattle Times described as “highly creditable.”

Except, as the student newspaper put it, for “a peculiar legal point.” The Supreme Court, gatekeeper of the Bar, declared itself in doubt whether a native of Japan was “entitled under the naturalization laws to admission to citizenship.”

This doubt dated to one of the earliest acts of Congress, which had offered a shot at citizenship to any “free white person” on American soil. Citizenship was expanded after the Civil War to embrace those of “African nativity or descent.” And while an 1882 law specifically excluded the Chinese from the privilege, Congress had never said, specifically, whether someone from Japan was in or out.

Washington State Attorney General W.B. Stratton had no doubts. Yamashita could not become a citizen, he and his two assistant attorneys general wrote, because “in no classification of the human race is a native of Japan treated as belonging to any branch of the white or whitish race.”

So the freshly minted law graduate from a small Japanese town made his own stand against the state’s top lawmen, in the marble halls of its highest court. Yamashita’s 28-page brief demonstrated writing and thinking of “solid professional quality” and legal strategies that are “quite original,” said civil-rights scholar Gabriel Chin of the University of Cincinnati Law School, who is devoting a chapter to Yamashita in an upcoming book on race and the law.

For starters, Yamashita argued that when Congress had defined citizenship in 1790, it could not have meant to exclude his countrymen because hardly any had ever been seen on the American continent. But his most memorable point was that shutting out a person on the grounds of race affronted the core values of “the most enlightened and liberty-loving nation of them all … in which all men are equal in rights and opportunities.”

This kind of talk drew the scorn of the state’s lawyers, who mocked Yamashita’s “worn out Star Spangled Banner orations.” Yamashita fired back that he owed no apologies.

Blocked from his chosen profession, Yamashita turned to a more typical 20th century immigrant path: business.

“Your applicant … knows of no tribunal to which an argument based upon the Declaration of Independence and the spirit of American institutions could be more appropriately addressed,” he wrote, “than to the Supreme Court of a free American state.”

On Oct. 22, 1902, a few days before his 28th birthday, Yamashita heard the Supreme Court’s unanimous decision: he was not eligible to be an American, and thus could not practice law.

Blocked from his chosen profession, Yamashita turned to a more typical 20th century immigrant path: business. His mentor Nishii bankrolled him in starting increasingly bigger restaurants in the bustling waterfront districts of Seattle and Bremerton.

Like millions of other immigrants, he maintained a web of contacts with his homeland, starting with a post-graduation trip to marry a grain trader’s daughter, Ito Nakagawa. Four years later, the couple returned to Yawatahama to give birth to a daughter, Haruko, who stayed behind to be raised by relatives. Yamashita made several more trips to Yawatahama throughout his life, and anyone visiting the secondary school today can find his name on the plaque of donors.

But the Puget Sound area was home. The Yamashitas had five children in Seattle, four of whom died before age 20 from tuberculosis, meningitis and “brain disease.” Beset by tragedy, Yamashita took advantage of American opportunity, opening hostelries where travelers would be seeking a meal and a shave, including the landmark Togo Hotel overlooking the bustling ferry dock in Bremerton.

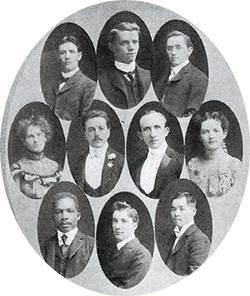

A page from the 1903 Tyee yearbook shows the remarkable diversity of the UW School of Law’s 1902 graduates. Yamashita is at lower right.

But public records never listed Yamashita as “owner.” Washington state’s 1889 constitution banned the sale of land to aliens ineligible for citizenship—in effect, Asians. This forced the immigrants to cast themselves as “managers” of businesses owned in the name of their U.S.-born children or cooperative whites. And Washington lawmakers tried to close even these loopholes in 1921 by banning Asians from renting land or renewing an old lease. Not only were the hotelkeeping Yamashitas threatened, but so were the thousands of the Japanese truck farmers supplying, by some accounts, three-quarters of Seattle’s produce and half its milk.

That’s when Yamashita, no longer a fresh school graduate but a 47-year-old businessman, committed his second major act of rebellion.

He and a fellow immigrant named Charles Kono filed articles of incorporation to create the Japanese Real Estate Holding Company. The xenophobic Seattle Star reported that the partners had gained control of “rich agricultural lands” in the White River Valley, where more than half the state’s Japanese farms were located.

When Secretary of State J. Grant Hinkle refused to register the corporation, Yamashita, this time, did not have to fight alone. He had an eminent New York attorney on his side, George Wickersham, a former U.S. attorney general who’d been hired by the Pacific Coast Japanese Association on behalf of a Hawaii resident named Takao Ozawa. Fearing that Ozawa might lose on a technicality, Wickersham needed a backup case. Thus did Yamashita help lead the Japanese-American counterattack against exclusion.

Bringing both cases to the U.S. Supreme Court, Wickersham borrowed some of Yamashita’s legal arguments from 1902—that Congress had singled out the Chinese for exclusion but was silent on other Asians, that Japanese immigrants had demonstrated their ability to fit into American society, and that the Founding Fathers’ vision of equal opportunity was “the highest ideal of Americanism.”

The outcome was the same as in Olympia two decades before. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously against Ozawa, and then cited that decision in rejecting Yamashita: Someone of the Japanese race and born in Japan was not entitled to be a naturalized citizen of the United States.

Even this setback did not seem to shake Yamashita. When the Navy took over his Togo Hotel to expand its shipyard, he bought the nearby Rainier Hotel. A couple of years later, he opened the People’s Café where he kept on feeding workers hungry from overhauling the West Coast fleet.

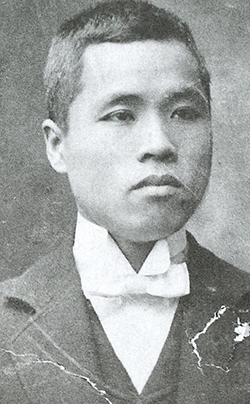

A young Yamashita poses for a formal portrait, perhaps taken at the time he attended the UW.

Yamashita had an ability to move on from even the most staggering losses, said historian Ronald Magden, ’64, who deserves much of the credit for Yamashita’s rediscovery. While researching his 1998 book on Japanese settlement of Pierce County, Magden found that interviewees who’d met Yamashita in his later years knew little of his courtroom showdowns.

“He never talked about it again, he just walked away,” Magden said. “I think that’s absolutely key to his character.”

That’s what probably enabled Yamashita to endure. In the mid-1920s, he buried a son and a daughter. What remained was the nuclear family of Takuji, Ito and Martha, a daughter born in 1910. Of fragile health like her siblings, Martha attended the UW for a year but dropped out in 1931 because of tuberculosis.

For all the heartbreak, this clan was a vibrant threesome. Fred Ohno remembers them as “a tremendously happy family” living on 20 acres of leased waterfront property in the town of Silverdale, a place where they could raise oysters and strawberries and let Martha inhale revitalizing country air.

“Takuji never complained,” said Ohno. “He was never bitter.”

Another teenage pal of Martha’s during the ’30s, Yoshiye Iwamaura, recalls the Silverdale spread as a social nexus for the region’s Japanese, who would ferry from Seattle for beach parties featuring roasted clams and sukiyaki.

But it wasn’t all play. Takuji joined the night oyster-harvesting crews after locking up the People’s Café. Ito cleaned and bottled the mollusks, and the outgoing Martha sold them to shopkeepers in Bremerton.

Except that after Japanese planes bombed Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Bremertonians wouldn’t buy from Martha anymore, according to her brother-in-law, Sam Nakao. That was the least of the problems. Like 110,000 others of Japanese ancestry, the Yamashitas were soon ordered to internment camps. On July 24, 1942, the family locked up the dream house they had just finished building in Silverdale, with a view that seemed to touch the mountains. They never saw it again.

As a distinguished Issei, or first-generation immigrant, Yamashita was elected a block leader by fellow inmates of California’s Manzanar camp, Iwamura said. But the internment was the blow that finally weakened his spirit. Unable to pay their bills during three years locked inside three camps, the family lost all its holdings. Takuji Yamashita, the brilliant scholar, returned from the camps to survive as a housekeeper for a widow in West Seattle, Nakao said. This lasted until 1957, when daughter Martha died, childless. Within a month, Takuji and Ito returned to Yawatahama for good. Two years later, Takuji, too, was dead.

These grim final events obscured from history’s spotlight a man who had directly challenged three of America’s major barriers against Asians: to becoming a citizen, joining a profession and owning land.

“They were first-hand witnesses to the disabilities such discrimination placed on their families, friends and communities.”

Quintard Taylor, UW historian

He was too far ahead of his time to be remembered when his battles were finally won. Not until 1952 could Japanese immigrants become U.S. citizens, not until 1965 did Congress put Asian immigrants on par with Europeans, not until 1966 did Washington voters (on the fourth try) repeal the Alien Land Law, and not until 1973 did the U.S. Supreme Court finally grant aliens the right to practice law.

This last hurdle—practicing law—was not trivial. Until it was overcome, Asians in many states could never field their own legal team. As UW historian Quintard Taylor points out, many of the major 20th century strides in civil-rights were made by attorneys of color—think Thurgood Marshall—who were themselves victims of discrimination.

“They were first-hand witnesses,” Taylor said, “to the disabilities such discrimination placed on their families, friends and communities.”

Concerns among Asian Americans today may run more to the government’s zeal in prosecuting Los Alamos physicist Wen Ho Lee, but securing the right of citizenship was the primal battle for their grandparents and great-grandparents. The meaning of their struggle reaches beyond one ethnic group. The only way to really understand American citizenship, writes historian Judith Shklar, is to study what it meant “to those women and men who have been denied it and who ardently wanted it.”

“This type of story needs to be told,” added Tomio Moriguchi, ’59, ’61, president of Seattle’s Uwajimaya supermarket chain and the son of another man who crossed the ocean from Yamashita’s hometown.

It wasn’t just time that hid Yamashita’s story, but also the space between continents. His Japanese daughter, Haruko, and her descendants knew little of his U.S. exploits. Little, that is, until Haruko’s grandson, Naoto Kobayashi, married an American and, in 1993, moved to Maine. The move sparked his curiosity about the ancestor who’d sailed to America so long ago.

“It was exactly 100 years since Takuji Yamashita came to America, and my wife was pregnant at the time,” Kobayashi said. “I felt some kind of destiny.”

He and his sister, Tokyo sociology professor Tazuko Kobayashi, began piecing together their great-grandfather’s story with Magden’s help and through pilgrimages to such sites as the Togo Hotel and University of Washington.

Takuji Yamashita never got to be a full American. But he has a great-great-grandson growing up in Maine, named Takuji. The boy speaks a little Japanese.

Steven Goldsmith is a writer in the UW Office of News and Information and was formerly a reporter for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

Yesterday and today: diversity and the UW Law School

When Japanese-born Takuji Yamashita rose to receive his diploma in Denny Hall on May 19, 1902, his 10-member graduating law class also included two women and a black man from Barbados.

The 169 students entering law school in fall 2000 included 21 Asian Americans but exactly the same number of blacks as Yamashita’s class: one.

African American, Hispanic and Native American enrollment at the UW law school has been in decline, in fact, since Washington voters in 1998 passed anti-affirmative action Initiative 200. The year it was on the ballot, there were eight black students in the incoming law class. The next year’s class had two, the fewest in a decade.

Declining diversity in Condon Hall is a source of deep frustration for Law Dean Roland Hjorth.

“Lawyers shape the law, and they will shape it better if the legal profession reflects the diversity of our society,” Hjorth said. “One can only get a diversity of viewpoints by getting a diversity of backgrounds.”

Officials say I-200 undermined the willingness of minorities to even apply to the state’s only public law school. The year after it passed, the number of African American UW law applicants plunged from 61 to 37.

The law school was a focus in the I-200 campaign. Katuria Smith, ’94, a white applicant from a low-income background, became a poster child for the measure when she sued the UW with the claim that she’d been rejected by the law school to make room for blacks and Hispanics with lower test scores. UW officials said she’d neglected to mention her working class roots on her application.

Lawyers for both sides are waiting for the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals to set a date for oral arguments. Michael Madden, the UW’s lawyer, said it could be a year before the case is decided. Washington state dismantled affirmative action when I-200 passed, but Smith’s lawyer, Michael Rosman of the nonprofit Center for Individual Rights, says a victory in her case could topple affirmative action in other states where it survives, such as Oregon.

Whatever the courts decide, UW law officials are redoubling their efforts to recruit students of color. Alumni Ambassadors—two dozen law graduates from diverse backgrounds—will contact minority applicants, answer their questions and try to give the law school a human face. Busloads of junior and senior high school students, meanwhile, will visit Condon Hall this year for mock trials and workshops to get a taste of law school life. And when teenagers of color aren’t visiting the law school, the law school will come to them, via an expanding program called Street Law that sends law students to selected high schools to teach basic legal principles.

Law schools, of course, traditionally recruit college seniors, but this focus on a much younger audience is no accident.

“The research bears out that if we plant the seed in seventh or eighth grade, then we have a better chance of convincing someone to consider us,” said Sandra Madrid, assistant dean. “Hopefully, the fruits of our labors will show up in the years to come.”

At top: Takuji Yamashita stands in front of a Bremerton storefront with two of his children, Joe and Martha, in a photo probably taken on the Fourth of July.