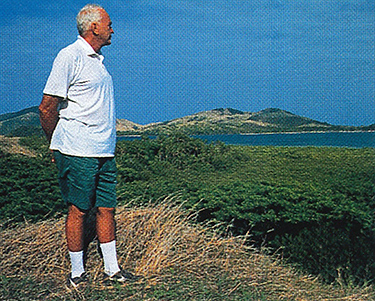

Richard Evanson, ’58, turned barren sand into luxurious Turtle Island

Photo courtesy Richard Evanson.

He had an engineering degree from the University of Washington, an M.B.A. from Harvard, and several million dollars in the bank after selling a Western Washington cable TV system to CBS. But in 1970, Richard Evanson, ’58, decided to leave Western Civilization behind.

Three decades ago, Evanson was 36 and burned out. So he headed to the Fiji Islands, armed only with a generator, refrigerator and a barge of beer. There, he used some of his cable TV fortune to purchase Vanuya Levu, a 500-acre, barren, uninhabited island in Fiji’s Yasawa archipelago and renamed it Turtle Island.

Both man and island were in bad shape. Evanson, who earned a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering from the UW in 1958 and later worked for Boeing, was a tipsy, overweight recluse. The island was a scorched desert, grazed bare by wild goats and decimated by storms and hurricanes.

Evanson dedicated himself to revitalizing the land, turning it into an ecological island paradise with the help of Fijian natives, who assisted him in planting 300,000 trees. He restored and preserved the island’s beaches and reefs, and re-introduced dozens of species of indigenous birds and wildlife.

Columbia Pictures was so impressed with Turtle Island that it convinced Evanson to let it film the 1980 movie The Blue Lagoon there. After filming ended, Evanson turned the studio’s abandoned cottages into guest suites and opened the island as a resort.

Today, Turtle Island is a renowned romantic private island retreat, featured in “Lifestyles of the Rich & Famous” and listed in Andrew Harper’s Hideaways’ Most Romantic Hideaway Resorts. Because Fiji straddles the meridian date line, it also hosted the world’s first wedding of the millennium on Jan. 1.

Evanson is also known as an ecological visionary. In the past 18 months, Turtle Island has received six prestigious international ecotourism awards for its innovative efforts over the past 20 years.

“I wanted to help preserve an island and a culture,” says Evanson. Through his approach of “sustainable tourism,” he says he has “a huge responsibility to present and future generations of indigenous people to ensure that we respect their values and heritage.”

Toward that end, he, Turtle Island guests and his Turtle Island Community Foundation have opened medical clinics, built classrooms and schools, and have worked to improve water quality, transportation and a wide variety of other services for the 2,500 residents who live at a basic subsistence level in eight villages on the six neighboring islands.

“This kind of work means so much more,” says Evanson, who puts his mechanical engineering degree to good use developing and maintaining the island’s infrastructure. “There are simply not enough people in our ranks within the tourism industry in our respective countries that are passionate about the issues of cultural integrity, environmental responsibility and ecological sustainability. We have to remind ourselves that we are living in their country, in their culture. We have to respect that.”