Readers pay tribute to their favorite professors

“I can at last thank you for all you’ve done for me,” writes one alumna to her dead mentor, who transformed her from a science hater to a science teacher. “(She) taught us that hard work pays off and secures your future. What better lesson can you learn?” says another alumnus of his extremely strict math professor. “He is the person our parents hoped we would meet when they sent us off to college,” writes another.

When we ran tributes on UW professors from nine alumni/authors in our last issue, we invited you to write the next page. Send us five or six paragraphs on your favorite professor and we’ll run the best essays in an upcoming issue, we said. You were listening. This summer, a flood of letters, faxes and e-mail came to Columns, and a few are still trickling in months later.

What follows are submissions from all alumni who sent us tributes to teaching at the UW by our July 1 deadline. The names are in alphabetical order and divided into those who made the print version of the magazine and all other tributes. We urge you to browse and discover the impact of teaching at the University of Washington.

14 professors featured in the print version of Columns

Henry Buechel

Henry Buechel

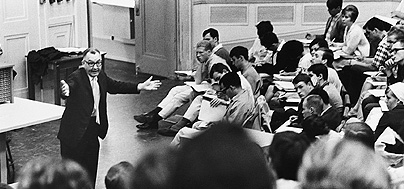

Here’s the picture. It’s the start of second quarter. You’re a sophomore in the middle of the famous “slump.” It’s 8 a.m. and very dark. Hey, it’s the middle of winter. You’ve either had too much coffee to wake up or not enough to stay awake. You make it to the huge lecture auditorium in Guggenheim Hall, get a seat as far away from the stage as possible and hope for the best.

Hope for the best because you’ve heard of this famous lecturer and his equally famous class, Economics 201.

Then he enters and begins one of his more notable lectures. It’s the one about the worker in the office of the president of the company, the one where he wants a raise or better working conditions. Anyway, the president puts his arm around this man and walks him over to the window, where he shows him a number of workers lined up for a job. “See all those men,” Dr. Buechel says, speaking as if he were the president of the story. “They all want your job. Now, do you think I should give you a raise and improve working conditions?” And off he goes on employee-management relations and the history thereof. Finally, after several weeks (which seem like 150 years), we’re ready for the next shocker…the Henry Buechel final. It’s something we’d all heard about but never experienced.

It’s a test every student on campus knew about even without taking the course. It consisted of 100 true and false questions. For every one you got right, you’d get one point. For every one you missed, you got two points deducted. Theoretically a person could get a negative score. I almost did.

I prepared. I reviewed notes, talked to other guys who had taken the test before, did some extra reading up, the whole nine yards preparing for this, the mother of all finals. I had an A going into this final. I got a C for the course. You figure it out.

Grades aside, it was a course to remember, and I did. Buechel was a great teacher, a riveting lecturer who would keep more than 200 students enthralled for 50 minutes three times a week for ten weeks. Then he’d do it all over again.

Michael Peringer, ’57, Seattle

Stan Chernicoff

Stan Chernikoff

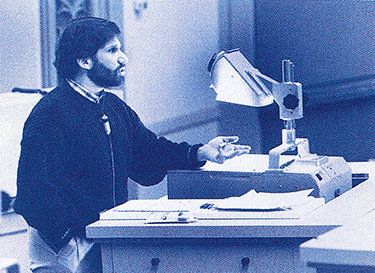

For nearly three decades Stan Chernicoff has enthusiastically educated the masses about subduction zones, pyroclastic flows and glacial moraines with an infectious passion that resonates through you with the timbre of his Bronx accent.

He was the first professor I approached for a quick question after class (astonishing, considering it was me and 700 other kids in his Geological Sciences 101 course). He called me by name before I even said anything, as he did nearly every other student in the class, and every student in the class the 10 years before me. I discovered a subject outside my major that I enjoyed immensely, finally understanding the value of a liberal arts education. He led us on field trips where I was astounded by his casual approachability, and came to genuinely like the person who was challenging me to better myself. As we tromped past hot springs on the way to Mt. Rainier or examined old sea beds on the way to Snoqualamie, we got the sense that this person really cared about us, and viewed himself as a steward to help us define our futures.

What I did not realize at the time was the breadth of Stan’s commitment to this University’s undergraduates. Over the years he has sponsored thousands of students for independent studies or internships. He has an open door that goes beyond office hours; he supports UW students in all their endeavors whether it’s attending their sporting events or honoring them at an awards ceremony. I am continually amazed at how he manages to keep himself fresh for the crush of kids that come around.

He is the person our parents hoped we would meet when they sent us off to college.

Clay Schwenn, ’93, Seattle

Erna Gunther

Erna Gunther

The Course: Anthropology 411, Indian Culture/Art of the Northwest Coast

The Year: 1951.

The Place: UW campus.

The Setting: The original Washington State Museum from the Yukon Expedition of 1909.

Enter through the pillared front doors, walk by mangy, stuffed animals, go up the creaky, worn wooden staircase, passing the bound Egyptian mummy, viewing the lower floor through a rickety rail, and finally, a small dimly lighted classroom.

Dr. Gunther, regal, arrives to share her expertise, intellect, and enthusiasm, delicately displaying chosen Northwest Coast Indian artifacts. The Kwakiutl spruce root hat with cedar bark cover is shown on her head as carefully as Queen Elizabeth placed the crown jewels of England. This classy lady was a female role model in an obscure subject on a predominately male oriented campus before, “You’ve come a long way, baby” was commonplace.

Occasionally, brief classroom experiences are remembered for a lifetime. I was lucky. Thank you, Dr. Gunther!

Nancy Meagher Hicks, ’52, Seattle

Mary Haller

Let’s go clear back to 1947-49 when the University was full of ex-GIs.

I’ll never forget the effect that Dr. Mary Haller, head of the Mathematics department, had on my college experience.

In my junior year in advanced mathematics, I registered for her class since the supposedly “easy” instructor’s class was already full. The “Doc,” as she was known, had a reputation for working students to death and I was more than apprehensive about attending her lectures.

About 20 students arrived at the first scheduled class meeting and naturally there was a lot of conversation about our immediate future. The “Doc” was not known for giving high grades. All of a sudden, here comes an imposing figure of a woman without the least bit of friendliness on her face. She wrote her name on the blackboard, turned to the class and said in firm tones, “My name is Dr. Mary Haller and I want you to be advised right now that all of you will do twice as much work as any other class, you will not miss a class unless you are near death, if you even drop a pencil during one of my lectures, you might as well transfer to another class. Now, those of you who don’t like my terms are free to go without prejudice.”

At the end of her announcement, at least 10 of the assembled group left the room without even a glance to see who was crazy enough to remain. When the door to the classroom finally closed, “Doc” turned to us and with a great big smile said, “Now that we’ve ridden ourselves of the quitters, let’s get started. I assure all of you that surviving this class will be a feather in your cap, and you will become good engineers.” True to her word, our class became as one and lifelong friendships started.

Dr. Mary Haller taught us that hard work pays off and secures your future. What better lesson can you learn?

Thomas E. House, ’42, ’49, La Puente, Calif.

A memorable teacher to me was Mary Elizabeth Haller, in the Dept. of Mathematics, circa 1948-58. She was an excellent classroom teacher, and brutal at the blackboard exercises. More was learned at the board than one could imagine. She gave me the confidence to go on to an M.S. and Ph.D., and later become a senior manager at AT&T Bell Laboratories. I have been Technical Editor for the IEEE Communications Magazine for over a decade, have four patents, and have given numerous papers and graduate colloquia.

B. Kieburtz, ’52, ’63, ’66, Portland, Ore.

Robert S. Hutton

Robert S. Hutton

When I was a scrawny sophomore in high school, I swore that I would never take another science class for as long as I lived. Only one teacher could change my mind. I met this teacher at the University of Washington five years later. His name was Robert S. Hutton Sr. of the Department of Psychology.

Bob (as students affectionately called him) was a brilliant man. His interests were as varied as the body of knowledge he possessed. Academically, he was well versed in physics, chemistry, biology, anatomy, physiology, neurology, and kinetics. During brief stints in the classroom he could be heard discussing jazz, baseball, mountain climbing, boxing, football, and Michael Jordan. He was definitely not a lonely face behind the overhead sharing information in a monotone voice typical of some professors. Rather, if you were lucky enough to pass the first test and not drop out of his course, he let you into his life, into his heart, into his very soul.

One 400-level neuropsych class began with no less than 50 students. Bob’s mental toughness and intestinal fortitude weeded that number down to 13 before the final exam. Bob invited the remnant 13 of us to his house in Issaquah for a pre-Christmas reward dinner. He had football muted on the television as a backdrop to the jazz music blaring throughout his woodsy cabin-like home. Framed Michael Jordan posters decorated at least one wall in every room. I took every single class I could that had his name attached to it in the course catalogue. I also volunteered as a human subject for one of Bob’s experiments on the M-wave and the H-wave. Later I became an undergraduate

research assistant for him. It was so exciting working with him. His work was cutting-edge. The nature of his research required expertise in many fields. He was the first and the only professor to encourage me to pursue a graduate degree. More importantly, he was the first professor to make me feel like I was much more than my student identification number.

In March, 1991, Bob suddenly passed away. He went into the hospital for a bleeding ulcer and had deadly complications. No longer would I choose another course coupled with his name or help him complete his research work. Nevertheless, Bob’s impact can still be acutely felt by my high school science students. I get that same fire of fulfillment in my eyes that Bob had in his every time a student grasped a particularly difficult concept. Every Christmas I remember the passion for learning Bob passed on to me and my desire to go back to school intensifies exponentially. Finally, beginning in the fall of 2000 I will pursue a Ph. D. in chemistry. Bob, I can at last thank you for all you’ve done for me by fulfilling your vision for my life.

Carmela Rivera Minaya, ’91, Wahiawa, Hawaii

Willis Konick

Willis Konick

When I first walked into Willis Konick’s class on Tolstoi, I hadn’t expected to stay, but by the end of the hour, nothing could make me leave.

Konick was unlike any professor I’ve encountered. Handsomely distinguished in a tweed suit, rocking on his heels with an impish grin, he began to sing something along the lines of “I only have eyes for you.” He wrote “love” on the blackboard in enormous chalk letters and started talking about romance. Here was some knowledge I could use!

A thespian at heart, Konick engaged in daily theatrics, calling classmates down front to act out scenarios that illustrated the emotional state of Anna Karenina and Prince Nikolai Bolkonsky. Other classes found him walking across our desktops or uniting the class in protest chants, enacting a nihilistic scene from Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons.

Over dinner at Haggett Hall, conversation often turned to my Russian Lit classes and “What had Willis done today?” His performances fueled our evening chats as we discussed topics from infidelity and motherhood to the nature of God as informed by Dostoyevski’s “Grand Inquisitor” argument. We almost felt like intellectuals, applying the philosophy found in classic literature to our contemporary lives.

Thanks to Konick’s unique teaching methods, my mild interest in Russian Literature, (based on Omar Sharif’s performance in Doctor Zhivago), became a full-fledged passion. I opted to take electives in Chekov, Pushkin, Gogol, Turgenev, and Dostoyevski, as well as Contemporary Soviet Literature.

This year, I complete a creative writing M.F.A. at Emerson College in Boston and begin to teach my own course in freshman writing. I can’t quite see myself marching across desktops or singing the Carpenters’ “Close to You,” but if I can make literature as relevant to my students’ lives as Konick did, I’ll have followed in a great mentor’s footsteps.

Nicole Vollrath, ’90, Allston, Mass.

“Don’t let go of me!” whispered the director in my ear. Without hesitation, I gripped a forearm and battled an awesome force pushing me to work harder and stronger. I didn’t let go.

The scene passed, class ended, my first quarter came to a close, and I recently graduated, but I vividly recall being an undeniable force in Gregor’s life in Kafka’s Metamorphosis. In retrospect, I was blessed with an opportunity to play a role created by a brilliant author and directed by a brilliant professor. There I began my higher learning.

Comparative Literature 271 was oft-prompted by an articulated narration of the “scene” in the novella we were reading. To assist in the description of the scene, the professor hand-picked a bashful student or two. Just then, Kafka’s presence was eminent. The air fell silent to a pedagogical transformation. Front and center Kane 120 rapidly became a stage. Elements of Metamorphosis took life and indeed the moment turned surreal.

PRESTO! We were all sitting in a Broadway playhouse watching the bare and raw talents of an awe-inspiring director getting the best out of aspiring actors (the students had no choice). Soon you saw flopping bodies and balancing acts…and you heard squeals, wicked calls, and laughter. The engaging physical metaphors from the scene left a visually stimulating interpretation for the student to find in the text.

The professor/director beautifully laid out the scene in a manner conducive to learning. The scene pushed the student to go beyond the literature. It was a visceral inhale of art. It acted as an entrance to a world of wonder.

This professional richly deserves my utmost admiration. Appraisal on the other hand, would not suit him well. He defines humble, in the sense that he teaches in an anonymous manner. The authors of the novellas created the path to learning, Professor Willis Konick guided us with his voice. Contrariwise, Professor Konick’s wisdom taught us to guide ourselves. Professor Konick, if you’re listening, “I thank you and I haven’t let go.”

Brett Drugge, ’99, Seattle

Vernon MacKenzie

I will never forget my first meeting with Vernon MacKenzie, by far my favorite (and most memorable) professor at the University School of Journalism, as it was known in the ’50s. An AP war correspondent in Europe during the fiercest days of World War II, Prof. MacKenzie was renown as the last man alive to have interviewed both Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini.

One can imagine the stories he had to tell, and tell them he did. My assignment was to interview MacKenzie about his interviews of The Evil Twins, and I made an appointment to meet in his Lewis Hall office. When he opened the door to his private office, I was overwhelmed by a huge Nazi flag draped over a couch that stretched from wall to wall. Turns out that this flag once flew over the SS headquarters in Berlin, and MacKenzie commandeered it for his own just before he left Germany for home.

MacKenzie taught a course in “propaganda” in the mid-50s, and, as you might imagine, it was always full, with a waiting list. He could regale his students for hours with stories about his war experiences, and his interviews and conversations with the famous and infamous.

He also taught a beginning course in news reporting, and he always told his students on the first day of class, “You will get a flunk for the day if you misspell (1) my name or (2) the word “it’s/its.” Even today, almost 50 years later, I never misspell it’s (or its). It’s amazing how often I still see the word misspelled, even in full-page ads or on neon signs or billboards!

Vernon MacKenzie was one of the greats of UW Journalism.

Rolf D. Glerum, ’55, Portland, Ore.

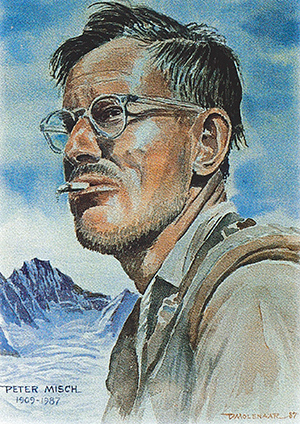

Peter Misch

Peter Misch. Art by Dee Molenaar.

The Office of the Department of Geological Sciences has framed a watercolor portrait of Professor Peter Misch, surrounded by reproductions of a selection of his alpine landscapes, which represent a childhood interest that preceded his development into a world renowned geologist and teacher.

As a mountaineer and skier, and artist, Misch was somewhat of an anachronism during his 40 years within the department; he believed strongly that understanding “the language of the rocks” required heading into the high hills with rock hammer, climbing gear, and two weeks of groceries. It was through his zestful rock-seeking scrambles through the Alps, Pyrenees and Karkoram Himalayas—along with close camaraderie with like-minded, mountain-loving students—that he attracted so many to seek him out as their theses adviser. During his tenure, Peter (as his grad students came to know him) supervised the M.S. and Ph.D. thesis projects of more than 125 students, with study areas that ranged among the mountains of the Pacific Northwest, Canada, Alaska, eastern Nevada, Great Britain, Africa, the Arctic and Antarctica.

Born in Berlin in 1909, Hans Peter Misch started doing many things early in life—painting watercolors at 5, skiing at 6, collecting fossils at an outlying farm at 10, and taking up serious mountaineering at 14. As a “wunderkind” geologist, Peter received his doctorate at age 23 from Gottingen University, with his thesis that covered the geologic structures and petrology of the central Pyrenees in northern Spain. Because of his strong combined activities in geology and mountaineering, Peter was invited to join the scientific contingent of the 1934 German Nanga Parbat Expedition to the Karakoram Himalayas.

It was through these wide travels among the world’s high mountains that Peter had become an avid supporter of the controversial theory of granitization, whereby—rather than occurring principally as an intrusive igneous rock—granite is found in the core of most ranges as the end-product of a metamorphic cycle that changes mud-to-shale-to-slate-to-phyllite-to-schist-to gneiss and finally to granite.

By 1936, Hitler’s persecution of anyone of Jewish ancestry had Peter with his wife and baby daughter Hanna leaving Germany for China, where during WW II he taught at Sun Yat Sen University in Canton before the Japanese invasion of Manchuria forced his move to Peking University in Yunnan. But his wife became ill and with Hanna returned to Germany, where she died during the Holocaust. Peter was not reunited with Hanna until at age 16 she came from Germany to Seattle.

After the war, Peter had come from China to California, where he taught briefly at Stanford and met and married the vivacious and equally talented Nicoletta (“Niki”) Rosenthal. After Peter was lured to the UW in 1947, Niki became his helpmate as they found their home among geologists, students, mountaineers and skiers of Seattle, while raising their sons Felix and Tony. And among Peter’s greatest joys in the post-war years in Seattle was to regain contact with some of his Chinese students, some of whom had survived the Cultural Revolution and attained respected positions in the scientific community of China.

Despite a rapid-fire, German-accented delivery in the classroom, Peter’s daily lessons were enhanced by his illustrative talent. By the end of each daily session his blackboard was covered from end to end with chalked sketches of geologic cross-sections of mountain ranges, showing faults, folds, and overthrusts he’s discovered during his wide travels among the world’s mountains. But of course his favorite outdoor laboratory was the North Cascades, where he spent nearly 40 summers mapping the geology under grants from the GSA (Geological Society of America), and there he encouraged many of his grad students to find their theses areas. It was my privilege to join Peter as his field assistant during the summer of 1950, and there I gained deep respect for his binocular recognition of distant geologic structures and rock types, and his rapid interpretation of the Big Picture, along with hammering and packing out heavy loads of rock samples. The field studies always included scrambling up the peaks and rest breaks for doing pencil sketches and watercolors of views across the deep, glacier-cut valleys.

On Peter’s 70th birthday, he received from Niki a thick notebook containing entries from more than 80 of his graduate students. The love and respect for the old professor came through with numerous anecdotes about his lectures, geology field trips, wine-tasting sessions at the Misch home, and skiing escapes from the classroom (which he encouraged among his grad students), along with a sprinkling of limericks featuring their favorite “earthy scientist.”

Most students who didn’t go on to grad school were unaware of Peter’s watercoloring talents. Most of his colorful and geologically detailed landscapes were stacked in the basement, and those who visited the Misch home noted only a few framed paintings on the walls—a couple Cascade peaks, a desert sunset in Nevada, and a desert, lake, pagoda and wave-splashed coast of China.

After Peter’s passing, Niki allowed me to select my favorite—a view of Mount Triumph done while we sat painting from a high meadow in the North Cascades—now a treasured memento of a good friend and inspiring teacher.

Dee Molenaar, ’50, Burley

Paul Pascal

Paul Pascal

How anyone could be fascinated by Greek and Roman mythology puzzled me. I had always found the myths too improbable, violent and difficult to follow with all the complex, consonant-filled names of characters. In the summer of 1970, I was squeezing my class load into the busy schedule of a mother of four young children and a commuter from east of Lake Washington. I worked as an elementary school librarian and was in the midst of earning my master’s degree in librarianship. I had enrolled in Paul Pascal’s class, Greek and Roman Mythology, because of the many references to the mythical characters and incidents in stories and paintings.

Dr. Pascal was the consummate storyteller: knowledgeable, articulate, funny, dramatic, and possessed of an impressive vocabulary. The large class sat silently so as to catch every nuance and every aside. He made those Greek and Roman gods come alive for us. We came to know all their conflicted personalities. We learned principles of mythology that we could see played out in our own lives. For instance, who has not noticed that Cupid shoots his arrows into the most unlikely combinations of lovers! Dr. Pascal also inspired a strong interest in etymology by weaving in Greek and Latin words with explanations of their original meanings.

The following spring I traveled to Greece and was able to apply my learning to geography, exhibits, statuary, and architecture. I have never been so prepared to visit a foreign land, and I still enjoy connecting the myths to art, literature, and psychology.

The class notes sit on my bookshelf and I refer to them now and then. My life is richer thanks to Dr. Pascal.

Jill A. B. Andrews, ’71, ’93, Vashon Island

When we read the “My Favorite Teacher” issue, I had one response: no one wrote about Paul Pascal??!! Allow me to correct that oversight.

I entered the U as an art major, but a savvy advisor suggested I “look into” Classics 210 (27 years ago and I still remember the course title). Paul Pascal had me from day one. Over the course of my undergraduate career I took every course that had his name next to it in the Time Schedule. The “Classics” were “hep” to Paul Pascal (he delighted in using the word “hep” as a sort of “in” joke). His sense of narrative and drama kept me mesmerized. Lucretius became my favorite poet and I knew the Aeschylus plays by heart. His passion became my passion. But he was no pushover. Even SPELLING counted in the grueling (you MUST remember this!) essay exams.

As recently as two years ago, I visited the Peloponnesian peninsula and, soaking up the local history I thought, so FONDLY, (and so VIVIDLY) of those early years in Pascal’s classes. Who knew at 18 what lifelong appreciations and understandings were being awakened by a passionate, articulate, FUNNY, walking Classics encyclopedia? Paul Pascal was a treasure.

Pat Rampp, ’76, ’84, Seattle

Roger Sale

Roger Sale

In the late ’60s, the University of Washington sponsored a federally funded summer program called Upward Bound. Unlike an easily mistaken program called Outward Bound, Upward Bound provided high school students from economically disadvantaged communities with the opportunity to prepare to enter the University of Washington.

Professor Roger Sale, along with Professor Jack Brenner, taught English in the Upward Bound program. Professor Sale, affectionately and sometimes not-so affectionately called, “Rog,” was the Bounder Class of 1970/71 first encounter with beings from higher education. During the course of our first summer, he became the one with whom we tested our so called “street” knowledge and wit, even though few of us really possessed such knowledge in 1970. However, since we looked the part and assumed he perceived us in this role, we attempted to challenge him by asking questions charged with controversy. I believe somewhere in our high school minds, it was important to establish our identities, to show some superior knowledge in an attempt to counter balance a sense of lacking and put us on equal footing. Professor Sale, with his establishment cigars and hippie-like hair, saw through our obvious attempts and without offense engaged us in discussion that led to an understanding of our true selves and strength of that knowledge.

When we returned the second summer, we knew the work Professor Sale expected from us. Our discussions were charged with inquiry trying now to get from him what he saw in the assigned readings. However, he didn’t want us to see simply what he thought, but instead pushed us to think beyond him, which was our real challenge. And so, each Thursday evening before papers were due, the dorm was quiet in contrast to the earlier part of the summer before. In the first summer, he challenged us to know about who we were and, now in our second summer, he was having us look outward to interpret the world around us. Although two summers were too short to impart all the critical thinking techniques we would need, he provided glimpses of what would be expected when entering the UW that coming fall. Glimpses were certainly more than would have had otherwise.

The statistics would show that the success rate of Upward Bounder participants is very low, hence the program no longer exists. However, the Bounder Class of 1970/71 did produce an editor of the Daily in 1976 and an English professor. Although many of us may not have succeeded by completing our academic studies, we have succeeded in other aspects of our lives. All of these accomplishments are attributed to the dedication of Professor Sale, Professor Brenner, Ralph Hayes (the late Seattle Public School Educator and African-American Historian) and Rick Nagle, Franklin High School educator, all of whom we owe deep appreciation for showing us what we could achieve.

Jeanette Martin, ’76, Tacoma

David Shields

Professor Shields always wore black, even on warm days. He would swoop into the classroom, raincoat billowing behind him like a cape. Taking his place at the square of desks, he’d peer at us like a hawk examining its prey. He was a real writer, very Greenwich Village, and I was duly intimidated. I don’t recall ever having called him David. We didn’t go out for coffee after class. He was there, not to be my pal, but to teach me how to write fiction. I trusted him utterly.

I took beginning short story writing with him in the fall of my sophomore year. His comments on my stories were blunt and specific. He strongly encouraged me to come up with better titles than “My Mountains” and “Chasing the Dream.” He urged me to cut my unnecessary verbosity and impossibly long sentences. But he was liberal with praise when he liked something. I knew exactly where I stood with him every week.

I jumped at the chance to take his year-long novel writing class during my senior year. There was space for only 15 students, which Shields selected based on writing samples. In the basement of Padelford, a woman looked up my name on the list of candidates. My whole future as a novelist was riding on that moment.

“He says ‘Yes,'” the woman finally said. Elated, I was one of the chosen few.

I haven’t become a novelist (at least not yet), but I have made my living as a writer for the past few years at the University of California, Davis. I’ve also published a few essays as a freelancer. What David Shields taught me about fiction has served me well as a non-fiction writer. I’ve kept all my manuscripts with his comments on them. I read them every so often and relish his praise—and cringe at his criticism.

Maura Brown Deering, ’91, Davis, Calif.

Carl Solberg

Carl Solberg

No one impacted my life more than History Professor Carl Solberg. As a lecturer, Solberg was incredibly dynamic. He rarely used notes and was always excited about whatever topic he brought to his podium He had the unusual ability to make something like the history of the Argentine tariffs very compelling.

I still have vivid memories of a graduate colloquium he taught during fall quarter, 1971. Students had to conduct detailed research into some aspect of Argentine history and then discuss it while dealing with questions and criticism from their peers. It was a tough assignment and Solberg relished every moment, directing the whole production masterfully while giving each of us an unbelievable introduction to the world of history in the making.

Solberg was also a product of his times. Casual in dress, handsome and always in superb physical condition, one always detected enthusiasm as well as confidence. He drove a battered Volkswagen for many years and lived in modest apartments. Solberg was a bicycle enthusiast who loved the outdoors and was captivated by the beauty of the Northwest. I recall occasional complaints but in general he was satisfied with his role; in l970 he told me that he “had a good life—I make $14,000 a year.” On the other hand, he was not reluctant to criticize the Vietnam War and for a time embraced the humane aspects of Marxism, particularly the regime of Chilean President Salvador Allende.

His personal life was wild and he did as much as possible to conceal it. He favored the sorts of nightclubs and taverns that had no windows. Although I was something of a bon vivant in those days, he left me in my tracks. Going into Seattle for a night on the town with him was real eye-opener.

It broke my heart when he died of AIDS in 1985. In severe pain, he was placed on several drugs, including morphine, until finally slipping away. Throughout a UW career that began in l966, he was extraordinarily enthusiastic about teaching and research and for that alone he was a respected colleague whose promotions received unanimous endorsement from the history department. Solberg’s students twice nominated him for the University’s Distinguished Teaching Award. It is a shame he never won that coveted prize because he certainly deserved it.

Professor Douglas W. Richmond, ’68, ’71, ’76, Dept. of History, University of Texas, Arlington

Peter Sugar

I entered the UW with many of my classmates from Roosevelt High School in the fall of 1961, transferred out of state to a small liberal arts college for my sophomore year, and returned in the fall of 1963—enticed back by that thick catalog of wonderful offerings. I graduated on time with the class of 1965. It was the UW history department that provided me with so many of the intellectual underpinnings that have kept me engaged in education ever since. I can’t recall having had a bad professor while at the UW, but for me, Peter Sugar represented the very best of what the University had to offer in those days.

I can still picture him on foggy January mornings, slinking across the Quad in his trenchcoat and signature beret like some mysterious apparition. He was so short that I can recall several occasions when he pontificated from a small ladder. His unique lecture style and his strong personality, combined with his thick Hungarian accent and his powerful command of his subject matter, made him a mesmerizing force in the classroom. I recollect as though it had occurred last week, the blistering critique he delivered of a report given by a fellow student who had committed the unforgivable act of consulting—in an entirely uncritical way—Nazi sources. I shall never forget the way he leveled the poor habits of scholarship while sparing at least some vestige of dignity for the frightened soul who had unwittingly fallen into that particular snare. When Dr. Sugar’s book on The Industrialization of Bosnia-Herzegovina was published, I was the first student to claim a copy at the University Book Store and certainly the first to have mine signed by Peter Sugar himself! I even memorized the inscription: “To Mr. Morgan who, if he keeps the promise he made in my class, will one day make me proud to have been among his teachers.”

There can only have been a handful of students on that huge campus who were reading Hugh Seton-Watson’s Eastern Europe, 1918-41 the semester I took Dr. Sugar’s course on that topic, but it still holds a special place in my personal library. I also know that any perspective I have on the current crisis in Kosovo or the larger issue of continuing conflict in the Balkans I owe to that diminutive man with the exotic persona, the big voice, the amazing intellect, and the occasional encouraging word. I have spent my entire professional life in independent schools, both as a teacher and as a headmaster. For the good part of that three-decade span, I’ve been in the classroom teaching history and French. Peter Sugar, and a number of other great mentors from those days in Seattle, were critical forces in inspiring my career path and in shaping my intellect.

It makes me sad to think how many outstanding teachers (including the formidable Miss Clark at Roosevelt High) never realize the impact they have had upon generations of students who grew up under their care and guidance. I salute Columns for providing this opportunity to pay homage to the great professors who have made the University of Washington’s reputation for excellence in undergraduate education so well deserved.

Gregory Morgan, ’65, Mechanicsburg, Pa.

Joan Ullman

Joan Ullman

Tonight my office is the Meson del Cid Restaurant, in Burgos, Spain—overlooking the Cathedral, which in turn overlooks the vast Castilian plains. If for Proust ruminations on a madeleine could conjure up a world of associations, for me it’s the lamb chop—the perfect dinner with a hearty Duero wine. The chop puts me in mind of the Mesta, the medieval sheepherders’ guild…which in turn recalls Professor Joan Ullman’s Spanish history lectures, which indirectly set me on the road I now follow.

Start with geography, she said—Iberia as outstretched bull’s hide with its mighty rivers uniting and dividing the country, its mountain ranges walling in distinct regions. Phoenicians, Romans, Goths, Arabs—we considered all their contributions. It was the 1960s, and the knowledge that once three dissimilar cultures lived in peace and cooperation — Jewish-Arab-Christian culture in medieval Iberia — was seductive. Professor Ullman did not allow the romance of this convivencia to blind us to the power of institutions and their intolerance, which in time undermined that great and rich society.

Enter the lamb chop. Today, as I crisscross Spain I often think of the sheepherders’ guild and their control, wealth and power, with its lasting effects on Spain, and intriguingly and indirectly on Latin America. Add the Mesta, the army and the church, and you have the institutions that have shaped so much of Iberia’s human geography.

In the 1960s, Professor Ullman’s lectures on the 20th century Spanish Civil War seemed particularly meaningful and poignant. Now in Spain, I regularly meet Spaniards too young to remember the post-Civil War dictatorship. In a noisy café, I sometimes conjure up a Joan Ullman lecture on the post-Socialist government, on the effects of youth unemployment on the social fabric. So much of the meat of her teaching has stayed with me—like a satisfying Castilian stew; I am much in her debt. And there is still so much to enjoy—from the rolling plains with their great pilgrimage history in the north, to the purple bougainvillea cascading down the ruins of a hill top castle somewhere in sunny Andalucia. Like Proust’s madeleine, my first bite of Castilian lamb released a whole history.

Sarah Banks, ’71, Seattle

Tributes to other professors

Sverre Arestad

When I embarked on an academic career in the late ’50s—at age 45, a housewife with seven children at home, it was Dr. Sverre Arestad, the head of the Scandinavian Department, who gave me the most encouragement.

Under his guidance, I was able to earn a teaching certificate as well as a master’s degree in Scandinavian Languages and Literature.

My tuition was mostly paid for by scholarships and I attended classes early in the morning and evening, riding on buses to the campus from my home near Bothell. After I started teaching Dr Arestad arranged for both my teacher-husband and me to attend seminars following our last class of the day so that we both earned master’s degrees at the same time.

It was through Dr. Arestad’s recommendations that I was able to attend UCLA one summer as part of a team of educators writing a text book for the teaching of Norwegian.

Although I became an English teacher, I also taught Norwegian classes at night school whenever there was an interest shown for the class, mostly at Shoreline Community College. Now I have retired from teaching and live in the San Juan Islands. However, occasionally I still teach Norwegian classes at Skagit Valley College.

When I consider the rewards I received through a long successful career, I would like to give credit to this wonderful educator, Dr. Sverre Arestad, who advised, encouraged and helped me and many other students achieve our goals.

Gurina McIlrath Palmer, ’63, Friday Harbor

How pleased I was to read of your offer to alumni to write about a remembered professor from earlier days at the UW. Like Ann Rule (from the early ’50s), I, too, remember Mark Harris from a later date. How well I recall the 20 or so students sitting around a large table in Parrington Hall for novel writing … only by the early ’60s he was reading aloud the students’ writing efforts. I remember his reading from my “novel” and his continual stopping to laugh. “This one reminds me of ‘The Egg and I,’ ” he chuckled. I was pleased at his response for, indeed, I didn’t mind comparison to Betty McDonald.

In addition to Mark Harris, I want to pay tribute to Dr. Sverre Arestad of the UW.’s Scandinavian Department. He taught Norwegian language and Scandinavian Literature… and what a dynamic professor he was! I well remember my first day in Norwegian 101 in September 1960. He took roll call by calling student names with a Norwegian pronunciation. My name was Mary Steen and although I had grown up around Norwegians, I had never heard the last name pronounced ‘Stay-en.”

“Mar-ri Stay-en,” I heard Dr. Arestad say. “Mar-ri Stay-en.” After the third or fourth time, I thought maybe he’s saying Mary Steen, so I finally responded. I loved that class, took every Norwegian class I could for two years, and ended with a minor in Norwegian and a major in English (writing rather than lit.) How I wish I could have had Dr. Arestad before my junior year because he really encouraged me to go into teaching (and, as he put it, perhaps I could also teach some Norwegian in whatever school I was in). Thanks to Dr. Arestad, for the first time I truly became interested in teaching as a vocation. However, I was determined to graduate in four years … so maybe, I said, I would return to obtain a teaching certificate.

Although I’ve worked for three school districts from writing and editing work in one district to theme reading for the past nine years in Kent School District, I have never gone back to school for my teaching certificate. I think often of Dr. Arestad and how I should have listened more carefully to him—in English.

Mary Steen Story, ’62, Renton

Nelson Bentley

I most vividly recall, from my student years at the University of Washington, the writing courses taught by the late Nelson Bentley. In other writing classes, when papers were presented, every effort was put forth to protect our slender egos. This approach was both helpful and appreciated, yet one could often sense an instructor’s struggle not to slap the side of his head and leap from the classroom window.

In contrast, Professor Bentley would appear to scarcely contain his glee while discussing our class assignments. He could always determine something of value in our papers, whether it was a unique subject, clever phrase or even a character’s unusual name. I vividly recall his redemption of one of my papers by finding great delight in the geographic location, which was a small city on the Washington coast.

I studied with some wonderful teachers, while a university student, though none exhibited the classroom enthusiasm of Professor Nelson Bentley.

Georgia Kravik, ’79, Seattle

Hugh Bone

Prescient Professor Hugh Bone has become—over the years—my favorite UW professor for having imparted political truths in the ’50s that proved invaluable and relevant during the fascinating impeachment of the ’90s.

Professor Bone told students a half-century ago that, while shocked Britons regularly oust politicians guilty of sexual affairs, less-prudish Americans historically have tolerated sexcapades of high office holders ranging from Thomas Jefferson to Warren Harding. He was explaining the then-current cases of British official John Profumo, forced to resign because of his dealings with call girls, and Sen. Warren Magnuson, who was attacked by opponents for frolicking with dancer Toni Seven. Magnuson was re-elected easily “because most Americans consider it normal for bachelors to have girlfriends,” Professor Bone concluded.

Though pro-impeachment forces last year incorrectly cited Gary Hart as an example of a presidential candidate ruined by sexual infidelity, Hart actually suffered a total loss of credibility after he publicly challenged the media to follow him and certify his purity.

House Republicans in 1999 could have foreseen the futility of using a sex scandal to try to oust Clinton—if only they had taken Political Science 101 from Hugh Bone.

Don Tewkesbury, ’54, ’56, Seattle

My favorite professor was Dr. Hugh Bone of the political science department.

Dr. Bone made his courses interesting by stressing real politics as opposed to theoretical politics. He arranged for his classes to meet and hear from the political leaders of the state and to visit the Legislature.

Dr. Bone was always objective—never showing a political party preference. I will never forget him saying, “politicians differ, not because there are two sides to every issue, but because there are two sides to every office—the inside and the outside.”

Harve Harrison, ’49, Edmonds

Jon Bridgman

I attended UW during the Vietnam War (’68-’72) and discovered Dr. Bridgman’s classes during my freshman year. Although I though I wanted to major in biology at the time, I never missed a class in world history. Even when I changed my mind and though I would major in French as a sophomore, I kept enrolling in Dr. Bridgman’s classes. One quarter I even skipped a third level French offering because a Bridgman class conflicted with it in the schedule. When I was a junior, my father asked what I planned to do with all of my science and French background, and I said, “Well, I think I’ll major in history!” Being a businessman, he wondered how in the world I would make a living with a history degree, and shook his head in disbelief.

Since then I have taught history in an alternative high school for 10 years to kids who had to have failed at least one history class just to get into mine. I used my old notes and blue books (do they still use those?) from Dr. Bridgman’s class to plan an interactive, theatrical course for them every year, and kids loved it! I’ve gone on to receive a master’s degree in guidance and counseling, where many of my history “skills” were quite useful: cause and effect; seeing both sides of an issue; and taking furious notes!

I’ve also sailed around the world on Semester at Sea and was able to see what I’d only heard about in the texts and lectures. It was an opportunity of a lifetime and I frequently thought about what I had learned in history classes as I experienced cultures and histories very different than mine. My enthusiasm and excitement for the world grew even more due to the contagious love of history I caught from my favorite professor, Dr. Jon Bridgman!

I was always amazed when Dr. Bridgman would say hello to me by name when we saw each other on campus. Once I remember that he called out my name in a 300 level class when I was a lowly sophomore and I almost died of embarrassment! But I kept coming back because I knew he loved his subject and personally knew me!

A special treat for me was obtaining a set of tape recordings of his spring lecture series on World War II. I saw them advertised in Columns and couldn’t wait for each month’s tape to arrive in the mail. It was like re-living classes with Dr. Bridgman every month. Will he ever do another series?

I’ll never forget those years and my experiences through an exciting time to be at UW. Thanks for the memories and GO HUSKIES!

Karen Connell, ’72, Erie, Colo.

Jack Cady

Jack Cady was always a little rough around the edges. His hair was askew, his clothes rumpled, and shoes needed a shine. But he had this beguiling smile that caught our attention. He always seemed to know something that we didn’t, and that smirk drew us in.

This particular English Lit class was during the spring quarter of about 1971 or ’72, and I didn’t have a clue about why I was there. I did enjoy reading, but writing anything other than a check to the UW for tuition was treading into the unknown. Jack not only made us all feel comfortable, but encouraged us to have some fun expressing ourselves. He said we were all to begin a journal, and simply record anything about the reading and class discussions that popped into our heads.

Now this was during a time of my life when school was a bit of a blur. I couldn’t wait to graduate, and get on with the rest of my life. I’ll never forget how that journaling exercise changed my entire college experience. With Jack’s daily encouragement, I slowed down, and actually took a closer look at literature. His anecdotes and musing were solid doses of inspiration. Not only did I garner an ‘A’ from Mr. Cady, but his energy carried over into my other classes as well.

Jack Cady lifted all of us up that quarter. His humor was infectious, his life experiences were entertaining, and he truly brought out the best in my marginal talents. Thank you, Jack, for your literary and inspirational legacy!

Richard Glazier, ’73, Lynnwood

Giovanni Costigan

With the arrogance of youth, I concluded that Giovanni Costigan was not on the cutting edge of historical scholarship. I became certain when his English history survey reached a period I had studied closely on my own. He was hopelessly old-fashioned, with his emphasis on the literature of the times and his requirement that we memorize the map of England in detail. His very appearance was a cliche, a wonderfully winning cliche, but a cliche nonetheless: the dark, formal suit; the curly white hair; the courtly gestures; the ancient bicycle; the theatrical, twinkling eyes. And, of course, everyone loved him, especially the non-history majors who had heard that this was a pleasant walk through a required social science. All of this should have prevented him from holding a place in my Pantheon.

But, during the spring of 1970, I was privileged to hear his lectures covering the period of the French Revolution. Our country and campus were awash with ferment in the streets and he delivered a lecture on Louis de Saint-Juste, the youngest member of the Committee of Public Safety. He emphasized that Saint-Juste had been our age and that revolutions properly belong to youth. With the slightest of lilts, Professor Costigan brought the fire of the Jacobins to Smith Hall. He won me over. Currency in French Revolutionary historiography mattered less than such a splendid lecture.

Then, the United States invaded Cambodia. Anti-war marches grew larger. Two buildings were bombed. Classes were a waste of time; some professors cancelled them; the administration authorized universal pass-fail. But we knew that Professor Costigan would continue to teach. There was so much to learn and his classroom remained packed. Then the National Guard shot and killed students at Kent State and Jackson State. At his next class, the bell rang to signal its start and we grew silent. Professor Costigan just looked at us sadly. His glasses with their colorless frames drooped in his hand and he shook his head. He did not approve of cancelling classes, “But,” he said slowly, “blood has been shed.” We left quietly.

Susan Vercheak, ’73, ’76, Maplewood, N.J.

I was delighted to read the My Favorite Teacher story in the June issue of Columns because my favorite professor, Giovanni Costigan, was featured. Timothy Egan’s story was excellent, but my view of Costigan was many years earlier when he first taught at the UW in 1935-36.

His classes were a joy. He even had open house some evenings for any of us students who cared to come to his home. I remember during this time when Kemal Ataturk was coming to power in Turkey, the class I was in was studying in world history. We were all anxious to hear Costigan’s views on the situation.

I took three classes at 9, 10, and 11 a.m. during a quarter from Costigan. It evidently so impressed him that years later when he lectured in Auburn I spoke to him, telling him how much I had enjoyed his classes and was surprised that he remembered me.

Marie Meyer Crew, ’37, Kent

Laura Crowell

There were so many outstanding professors that prepared me for a 35-year career in international affairs, especially the last 25 years at the Department of State, that it was difficult to choose just one. For 15 years I have told high school and college students from all over the United States about the importance of history in understanding foreign policy. I learned that from the greats like George Taylor and Solomon Katz. John Reshetar was responsible for my professional interest in the Soviet Union. Linden Mander inspired a lifelong interest in the United Nations. Hugh Bone prepared me for 30 years of political life in Washington, D.C.

One professor, however, honed the skills for group participation and speaking that I have used almost everyday of my career. Whenever I heard the words “I think we should do it this way” or “I believe we should … ,” Dr. Laura Crowell’s voice would remind me to phrase my input toward the goal of reaching a group solution. Most of the time I was representing the foreign policy position of the United States at an interagency or international meeting, usually in a controversial atmosphere where it was tempting to break Dr. Crowell’s rules. Negotiation and compromise, however, were the only way to conclude treaties, arms control agreements, or gain a consensus at NATO.

Dr. Crowell’s classes were intense clinics where your group participation and speeches were critiqued by her and the other students. At the time I was taking one of her classes, I also was running for student body president. Her personal attention concerning my goals and my ego, both inside and outside the classroom, rattled the very foundation of my college life and made me examine who I was and where I was going. Although I lost the election, I learned some valuable lessons about relating to other people and considering the views of others.

Thank you, Laura Crowell, wherever you are. Now that I have retired, I hope I can spend even more time passing on your valuable lessons to the students I talk to all over the United States about international affairs and how we need to respect the views of people from other countries as we try to solve conflicts and reach peaceful solutions to difficult group problems.

Gary B. Crocker, ’62, Arlington, Va.

Moya Duplica

Unquestionably the professor who made the greatest impression on me during my days at the UW (’79-’81) was Moya Duplica. At that time I was an undergraduate in the School of Social Work. After a year of classes in Kane Hall, I was more than ready for some higher learner on a more “personal” note.

I took at least three or four classes from Moya over a two-year span. What impressed me most was the genuine interest she had in her students, not to mention her obvious love for teaching. She was the perfect role model for any young, aspiring social worker — caring, professional, poised and quietly confident.

The last course I took under Moya’s tutelage was an independent learning class. I chose to do my report on the history of one of the most well-known social service organizations — the Salvation Army. In fact, my first job upon graduating was working as a counselor at a shelter for abused women and children, funded by the Salvation Army. Nearly 10 years passed and when I once corresponded by mail with Moya Duplica, I was more than flattered to find out she still uses my report in teaching one of her History of Social Welfare classes. If I hadn’t already been sold on her, the fact she could remember this undergrad some 10 years later blew me away! It’s an honor to “tip my hat” and give my personal tribute to this fine professor.

Jill Wright, ’81, Lynnwood

Donald Emery

I always believed that I had some of the great teachers in the history of the University of Washington. In truth I was privileged to have been taught by five of the 11 favorite teachers in the June Columns. These were Costigan, Johnson, Bone, Pressly, and Bridgman. (You can tell I was a social studies major.)

I would add an English teacher to the list. His name was Donald Emery. He taught an unlikely favorite course called English grammar. It was a three-credit course that I took to satisfy my requirement in English.

On the first day, I knew that I had encountered an unparalled wit. Every sentence we were required to parse was truly funny. (While his wit is stilled, I will always remember how much fun he imparted to our class.) He was not only a genuinely funny man, but a great teacher.

I will never walk across the Quad but that I can hear Dr. Emery waving and saying, “Hi Vinje.”

Jack Vinje, ’55, Bellevue

Arther Farrell and Douglas North

I have two favorite professors: one that taught me to love history for no greater reason than he loved teaching it, and the other for encouraging me to question, to step outside of the answer and look in.

Dr. Arther Farrell taught ancient history, and I sat in the very back of the auditorium drinking in his lectures. If I remember nothing else from his tutelage, the hoplite phalanx is indelibly inscribed in my mind … he even drew us an example of the formation for the overhead. My knowledge of ancient warriors scored me several points on a final “Jeopardy” question (watching at home mind you). Why did Dr. Farrell mean so much to me? Because he loved what he did, and his devotion spoke to me.

Now to Professor Douglas North, the distinguished head of the economics department (circa 1978). I chose a class that he taught in tandem with the head of the sociology department, not because I knew who he was; rather I needed a five-credit class to complete my credits for graduation. I hunted through “Soc” selections in the catalogue and came across a Soc 499 selection entitled “Economic Theory of Social Change.” I liked the title and the fact that it was sociology, therefore it couldn’t be too difficult. I later learned that this course was also listed under Economics as a seminar, and it was not going to be easy. I had made a major assumptive error.

I stuck with the course even though I was in over my head (a reluctant English major just trying to graduate). We walked through the Neolithic Revolution, into the Industrial Revolution in just three months, seeking catalysts for social change, sifting through economic and social conditions. The subject itself would fascinate anyone, but on a personal level, this was a growth class. For the first time in my academic career a professor of high esteem, a published author, told me one day that I had asked a very good question. Hallelujah, it was all right to ask, it was all right not to know. If he were a five-star general, I would have handed him a super nova right there on the spot.

As it happens, I took that course credit/no credit, and never wrote the final paper, though I had grand plans. I was hired by Pan American World Airways during finals week that year. Professor North gave me an extension to finish the paper over the summer, but I was based in Honolulu, and not about to set foot in a library, so I never wrote the paper. I did take the time to jot off a note to Professor North telling him how much I enjoyed the course; I even felt a glimmer of hope that he would pass me without the final, but he did not. When I received the “no credit” news, I signed up for a correspondence American Lit course that took two long, tedious years to complete.

It will be a cold day in San Diego before I forget what these fine professors and the University of Washington have done for me.

Mary L. Sherry, ’78, San Diego

George Farwell

One of the greatest adventures of my life began in one of those huge, impersonal, freshman lecture classes: “Physics Wave Mechanics.” Late in the quarter, the professor asked, “Does anyone have a question?” His response, to my question, was shocking and set off a series of events which are indelibly recorded in my memory. “That is the most stupid question I’ve ever heard. If you had done any of the required homework, you would realize how stupid your question is! In fact, if you had been listening at all to today’s lecture, you would realized just how stupid you are!”

Naive, yes; stupid, no! I headed directly to the Administration Building to see the University’s vice president of research: Dr. George W. Farwell, a nationally respected physics research scientist. He would know who was doing research in my field of interest and who could discuss my question in a reasonable manner. As we walked across campus, Professor Farwell’s two-sentence response was even more shocking, “David, there is no one on campus qualified to answer that question. Find a good institution and do the research!”

A few months later, I found myself proposing an experiment to the chairman of the Physics Department, Cal-Berkeley. Dr. Sumner Davis exchanged facial gestures with his assistant and stated, “That is such a subtle question. We will have to research the answer before even considering (assigning department resources to you).” Dr. Davis gave me his personal lab for the summer; he agreed to be the project’s theoretical adviser, and solicited Dr. Amer to assist with the equipment and experiment. Of course the question came up, “Why Berkeley and not the UW?” Professor Farwell’s statement was the accepted answer, “Find a good institution and do the research.”

My research involved the properties of laser light, and my lab was surrounded by people doing cutting edge laser research. I toured research labs at the Berkeley Livermore Labs and saw the insides of the cyclotron itself. Berkeley’s chancellor of student affairs came over for a dorm meal and to talk about my Berkeley experience. I was allowed to join a round-table discussion with my physics super hero, Dr. Crawford, and his protégés. “Dave you weren’t around when it was made, but today’s assignment is to present a simple wave experiment which can be done anywhere. What can you show us?” The trick I showed was at least 100 times more “ridiculous” than my original UW question. A funny thing was happening. No one was laughing at my latest proposal. Each scientist recreated the trick and reported what they saw. Those who disagreed with my hypothesis had to present their own explanations of the phenomena. I seldom had to defend my position, because someone else would interrupt to shoot down impractical explanations. The group continued discussing and playing with my trick while we walked to Dr. Crawford’s postgraduate lecture: “Making Wave Physics Interesting for Students.”

Early one morning as the first faint hues of sunrise silhouetted the hills behind the campus, I assembled a mathematical formula modeling light’s behavior. The formula verified that my original UW question was correct. Additionally, given any specific laser, the formula would predict when the phenomena could be observed. During the time, which it would take the rumble of distant thunder to follow lightning’s blinding flash, there was an all consuming feeling of success and genius. Then more calculations, a couple of hours’ sleep, back to class, back to the lab and more studying … a pattern which was being repeated throughout the surrounding labs.

Before leaving Berkeley, the physics department made it clear that until graduating from the University of Washington, I had a standing invitation to return each summer, “to carry your research to progressively higher levels.” Back home, I told only two friends—a grad student and a professor—about the Berkeley experience. That was more than enough; everyone found out. A frequently asked question was, “How did you end up at Berkeley?” The answer was simple: George Farwell.

Professor Farwell’s two-sentence response to my question remains shocking to me. But at the time, his statements seemed disorientingly bizarre. Here was a man with immense pride in his field of science and in the University of Washington. And he was saying, David don’t waste your time (and self-esteem) asking questions of people who are not qualified to answer. Take action, make decisions and take responsibility for your own discoveries. Through their words and actions, Dr. Farwell and the Berkeley professors empowered me to take full responsibility for finding an answer to my own question. No one ever told me the answer. They never hinted in what direction I should expend effort. There were lots of good institutions, besides Berkeley and the UW, where I could have done the research. (Today, the whole thing could be handled with two laser pointer-pens and the Internet.) Berkeley was the reward … one of the greatest adventures of my life, which resulted from George Farwell inspiring me to think creatively and to take responsibility for my own discoveries.

David W. Erickson, ’88, Seattle

Agnes Haaga and Geraldine Siks

As a recreation leadership major, with a goal of working in a youth serving agency, I was fortunate in taking a broad spectrum of liberal arts courses. But the best of what I learned about working with children was from two remarkable and innovative teachers in children’s drama, Agnes Haaga and Geraldine Siks.

They were equally able in their ability to instruct and inspire. Whether lecture, demonstration, participation or observing them playmaking with children, there always seemed to be a touch of magic in their classes. From them, I learned theory, philosophy, psychology, drama, and life.

Professor Siks was a poised and elegant woman who presented children’s drama with vision and clarity. Agnes Haaga bounced into class in a cloud of joy, fun and adventure. Individual conferences with her were punctuated by laughter and I always left feeling my abilities had been stretched.

These two gifted and charming women encouraged my creativity and a sense of accomplishment and pride. Not only skills to find the career I wanted, but to last a lifetime.

Mary Carroll, ’66, Redmond

Amy Violet Hall

You asked for a vote. Mine is for Professor Amy Violet Hall, of the HSS dept. in the College of Engineering, 1949 to approximately 1959. She ran against the grain of engineering students and tradition by advocating the worth of a liberal education for engineers, and introduced me to literature, famous thinkers of the last three thousand years, and the fact that there are several great world religions that have a lot to say. She was an idiosyncratic and inspiring teacher in the classroom and in the office.

- B. Kieburtz, ’52, ’63, ’66, Portland, Ore.

Mark Harris and Sverre Arestad

How pleased I was to read of your offer to alumni to write about a remembered professor from earlier days at the UW. Like Ann Rule (from the early ’50s), I, too, remember Mark Harris from a later date. How well I recall the 20 or so students sitting around a large table in Parrington Hall for novel writing … only by the early ’60s he was reading aloud the students’ writing efforts. I remember his reading from my “novel” and his continual stopping to laugh. “This one reminds me of ‘The Egg and I,’ ” he chuckled. I was pleased at his response for, indeed, I didn’t mind comparison to Betty McDonald.

In addition to Mark Harris, I want to pay tribute to Dr. Sverre Arestad of the UW.’s Scandinavian Department. He taught Norwegian language and Scandinavian Literature… and what a dynamic professor he was! I well remember my first day in Norwegian 101 in September 1960. He took roll call by calling student names with a Norwegian pronunciation. My name was Mary Steen and although I had grown up around Norwegians, I had never heard the last name pronounced ‘Stay-en.”

“Mar-ri Stay-en,” I heard Dr. Arestad say. “Mar-ri Stay-en.” After the third or fourth time, I thought maybe he’s saying Mary Steen, so I finally responded. I loved that class, took every Norwegian class I could for two years, and ended with a minor in Norwegian and a major in English (writing rather than lit.) How I wish I could have had Dr. Arestad before my junior year because he really encouraged me to go into teaching (and, as he put it, perhaps I could also teach some Norwegian in whatever school I was in). Thanks to Dr. Arestad, for the first time I truly became interested in teaching as a vocation. However, I was determined to graduate in four years … so maybe, I said, I would return to obtain a teaching certificate.

Although I’ve worked for three school districts from writing and editing work in one district to theme reading for the past nine years in Kent School District, I have never gone back to school for my teaching certificate. I think often of Dr. Arestad and how I should have listened more carefully to him—in English.

Mary Steen Story, ’62, Renton

Ryland Hill

I transferred to the University of Washington as a junior. My first two years were spent at Idaho State University in Pocatello. After one semester at Washington, I was called into military duty as an Army aviation cadet, returning two years later to get my degree in electrical engineering.

Two professors in the engineering school were most helpful for me—Professor Lindbloom took me under his wing and helped me greatly to get oriented into the electrical engineering courses. I later taught a laboratory course under his direction.

But it was Professor Ryland Hill who I have to pick as my favorite, since he not only helped me through my senior courses but became my mentor in understanding the real needs of an electrical engineer in industry. The obvious career path at that time for an E.E. was with one of the big electrical firms like General Electric or Westinghouse, but I was not happy with their indoctrination programs before I could start doing “real” engineering work. Professor Hill sat me down one day and told me about his short stay with Standard Oil of California in San Francisco. Now, there was a real engineering job for an E.E. I was very surprised with what he told me—”You mean that an oil company has all that varied work for an electrical engineer!”

I applied with Standard Oil and was pleased with their immediate response to come to San Francisco for an interview. I did and was hired on the spot. I spent 30 years with Standard before I retired, including several foreign consulting assignments. But the most interesting assignment was as a recruiter for engineering and science students at several universities, including the University of Washington. This provided me with the opportunity to visit with Professor Hill again—now dean of engineering. I spent a couple of evenings at his house over the years talking over old times and discussing what I thought would be the best educational direction for engineering students in the future. I also was administrator of several scholarships for engineering students.

John A. Ziebarth, ’47, Santa Rosa, Calif.

C. Leo Hitchcock

If you studied botany within the past 25 years, chances are one of your texts was C. Leo Hitchcock’s “Flora of the Pacific Northwest.”

It was spring of 1948, and, needing graduation credits, I signed up for Hitchcock’s summer botany field trip. The purpose of this particular one was to study and collect plants in eastern Washington, Idaho and western Montana, circling north through the Canadian Rockies and back to Washington. Sounded like an adventure for an English major who needed University credits.

“Hitchy,” as we called him, was an extremely energetic, rather gruff individual, who seemed determined to get one sample of every plant in the Northwest. These were placed on blotters, which were strapped together—the bulky plant presses.

Our group of about a dozen traveled over back roads in a big army truck, accompanied by a smaller panel truck. The army truck could be turned into a camp kitchen, with an awning that could also be used for protection at night. We enjoyed Hitchy’s morning biscuits and ate trout caught in the river before breakfast.

Plant collecting was strenuous. One four-night pack trip took us 80 miles along the Continental Divide. The scenery was spectacular, the weather less so, with heavy rain and snow. On occasion Hitchy would suggest a game of bridge; a communal washtub filled with warm water soothed the aching feet of the players.

One memorable test was given while we all ran along a path high in the Canadian Rockies. Hitchy would pause, pick a plant and pass it along for our identification. I had to struggle to keep up, and by the time the plant reached my end of the line, it was more or less unidentifiable! And the final question? Hitchy pointed to a ridge several miles away. We were to name the trees on the skyline! (Larch grows at that elevation).

Among our adventures—losing our way on a cross-country pack trip east of Flathead Lake and a 24-hour bout of dysentery suffered by us all the day we crossed back into the U.S.

I returned home with an abiding interest in exploring western lands, 12 hours of “C,” and respect for a truly great, if idiosyncratic educator! After 50 years I can still rattle off botanical names of Alpine plants.

- M. Mahon, Mercer Island

Edgar Horwood

The late Edgar Horwood was an entertaining and informative instructor. But more importantly he was an effective mentor of students. He pointed me to my first job as an entry level engineer. Then he encouraged me to return to graduate school for my masters in civil engineering and to stay on for my Ph.D. We continued to relate via professional associations, but it was not until his retirement party did I realize how many students he impacted in a similar way. And we all had humorous Edgar stories to tell.

Kenneth J. Dueker, ’60, Professor of Urban Studies and Planning, Portland State University

Francis Hunkins

Of the six universities at which I’ve studied or taught in various parts of the world, there is one that stands out above all others. It’s the University of Washington. And it’s not difficult for me to tell you why. I first arrived at the UW 21 years ago as a 44-year-old, nervously approaching doctoral studies within the College of Education. I had been granted only a very limited amount of leave by my own university—just enough, in fact, to be able to complete my residency requirements and my course work. My research and dissertation, I knew, would have to be completed back home in Australia. It was a very daunting prospect indeed!

I had been corresponding with my supervisor-to-be long before I left home and family, and it was quite clear that he was “testing me out” with his preliminary reading lists and descriptions of the various course I would take, including several of his own. This feeling — of being tested — was reinforced when I first met him. It wasn’t a negative impression, however, since it was obvious that here was a self-motivated individual, keen to learn, keen to assist others to learn and explore, keen to motivate, determined to get the best out of his students. I can remember the very relieved phone call I made to my wife that evening.

And so it went — a demanding man, yet encouraging; a professional who expected his students to achieve high standards, yet did this with warmth, good humor and reassurance. A top-class educator.

Our professional relationship soon developed into a true friendship. In the intervening years, our families have vacationed together (in both the U.S. and Australia), celebrated and commiserated together, and corresponded always. The relationship that started my ongoing regard and respect for the University of Washington and that has made me proud to be a life member of the alumni association, was sparked by this man.

Until my recent retirement, I taught at Monash University. Its motto is “Ancora Imparo” — I am still learning. Said to have first been proclaimed by Leonardo da Vinci, it applies just as accurately to my friend, Professor Francis Hunkins.

Philip Perry, ’81, Mt. Eliza, Australia

Daniel S. Lev

On the first day of Professor Daniel Lev’s Introduction to Comparative Politics class, he would hand out a syllabus in which each week of class was meticulously assigned to the study of a particular country’s political system. By the second week of the course, we were already hopelessly off schedule and would remain so for the rest of the quarter.

But that didn’t really matter. What made Professor Lev stand out from his colleagues was his willingness to spend class time discussing current events regardless of how much it diverted from his set agenda. He provided us with copies of the Manchester Guardian and compelled us to think and to analyze contemporary political developments throughout the world.

Perhaps it kept us from covering the course material in a more detailed or organized way. But Professor Lev’s students nevertheless were instilled with two, very valuable concepts: the responsibility of the electorate in a democracy to be informed, and the dangers which an ignorant populace faces when it fails to scrutinize its leaders. By learning about comparative politics, we discovered the stark contrasts between a political system in which a conscious public serves as a watchdog against the potential excesses of those in power, and one where an indifferent public is controlled by the corrupt few.

With his emphasis on current affairs, Professor Lev did his utmost to prevent the latter from happening. Since attending his class 16 years ago, I have read two newspapers every day, all because he compelled me to heed my responsibility as a citizen of a political system which allows me the luxury of partaking in it. It is a valuable legacy which will remain with me for the rest of my life.

Gregory Dziekonski, ’85, ’89, Seattle

Glen Lutey

I had some great teachers in my undergraduate years at the UW. Among them were Herschel Roman for genetics, Thomas Pressly and Solomon Katz for history, and Franz Michael for Asian studies (then it was called Far Eastern). However, the professor who stands out most clearly in my mind is Glen Lutey, who taught the last few courses in the catalog to bear the title, “Liberal Arts.”

At the suggestion of my advisor, for winter quarter 1953 I signed up for “Liberal Arts 101 – Introduction to Modern Thought.” I had no idea what to expect when I walked into the old worn down semi-circular lecture theater on the southwest end of Denny Hall — a very uninspiring setting.

When Dr. Lutey entered the room, I thought he looked like the stereotype of a college professor — gray hair, tweed suit with chalk dust, pleasant face, mild manner. I feared I was in for a boring class in a dull room. I couldn’t have been more mistaken.

For the next 10 weeks he took our class on a dizzying intellectual ride through the history of cosmology, the scientific method, astronomy, physics, the origins of life and of man, biology, anthropology, genetics, ending finally with the philosophical ramifications of it all. In short, he showed us how we had come to think as we had in the middle of the 20th century.