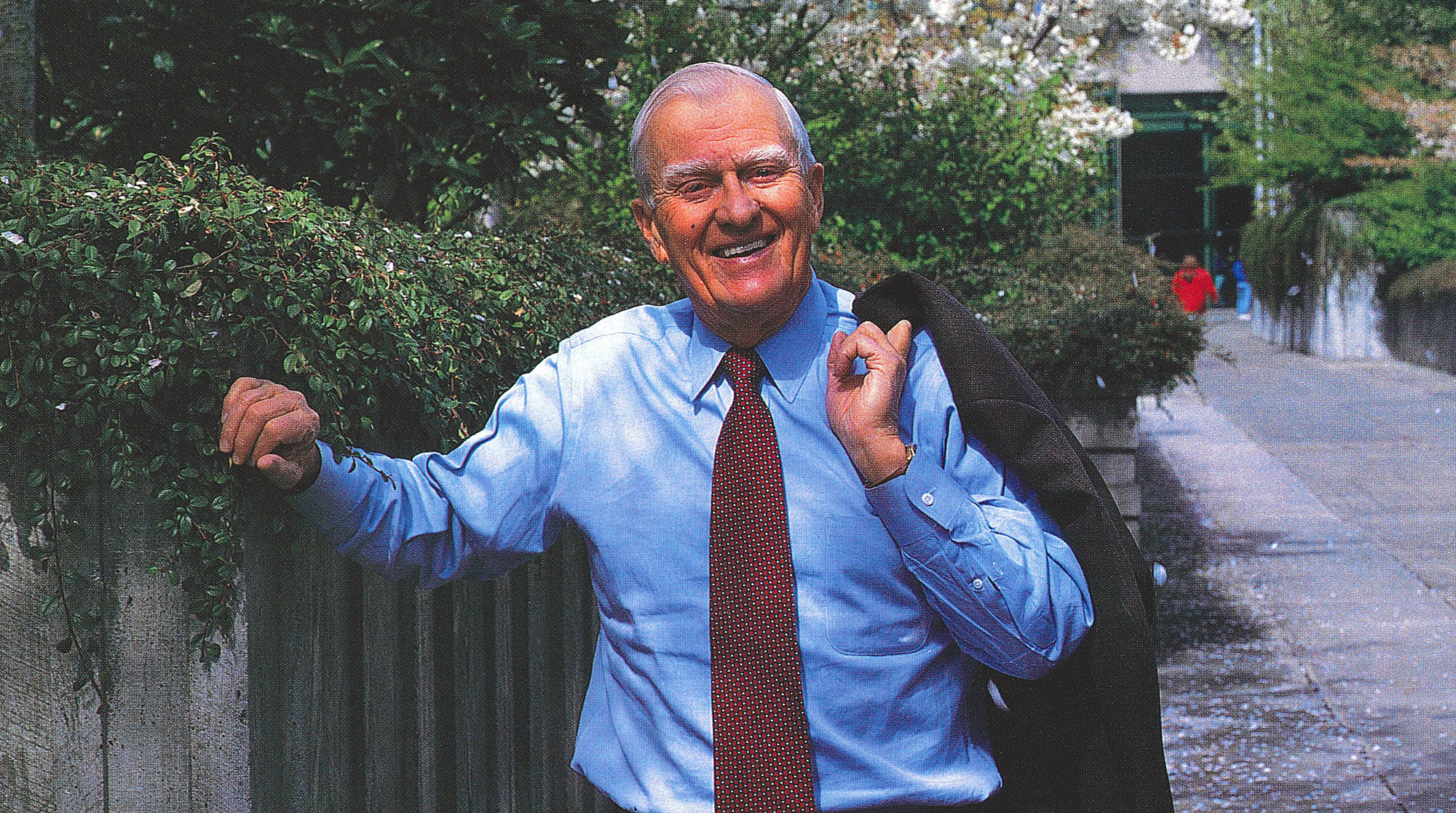

An artillery shell that exploded on a World War II battlefield near Trier, Germany, in February 1945 changed the course of the Puget Sound area forever.

On that winter day, a young American soldier by the name of Robert Ellis was killed in action during the Battle of the Bulge. His older brother, James, himself a young Air Force officer stationed back in Idaho, was utterly devastated by the news. He and his younger brother had been inseparable. As teen-agers, they built a log cabin east of Lake Washington with their bare hands. Jim always looked after his younger sibling, who was ill much of his childhood. Jim wanted revenge, and demanded to be sent to the front lines.

But his wife of three months, Mary Lou, interceded. Don’t go the front lines, she said. You could die. That isn’t what Bob would want. Why not do something to honor him?

Ellis stormed out of their hut and spent the next few hours tromping around in the snow. His wife’s last comment replayed over and over in his head. What did she mean by that?

Robert Ellis

When he returned home, he asked her to explain. “We could take part of our life and give something to others, for Bob,” she said. “How about conservation? Bob always liked that.”

With that, James R. Ellis not only achieved a measure of closure on his brother’s death, but got the inspiration for a lifetime of civic activism that would lead him to undertake some of the most far-reaching public service projects the Puget Sound area has ever seen.

In the 1950s, against overwhelming odds, Ellis spearheaded repeated efforts to clean up pollution-choked Lake Washington and start a county-wide transit system by creating Metro, a regional governmental agency. He was the chair of Forward Thrust, a grassroots community effort which secured authorization for the Kingdome, many parks and other public improvements. He engineered public acquisition of thousands of acres of endangered farmland, and fought for a “lid” on top of Interstate 5 in downtown Seattle to serve as the home for the Washington State Trade and Convention Center and Freeway Park. And today, among other things, he is heading up the Mountains to Sound Greenway Trust, an effort to preserve the green belt along the I-90 corridor from Cle Elum to the Puget Sound.

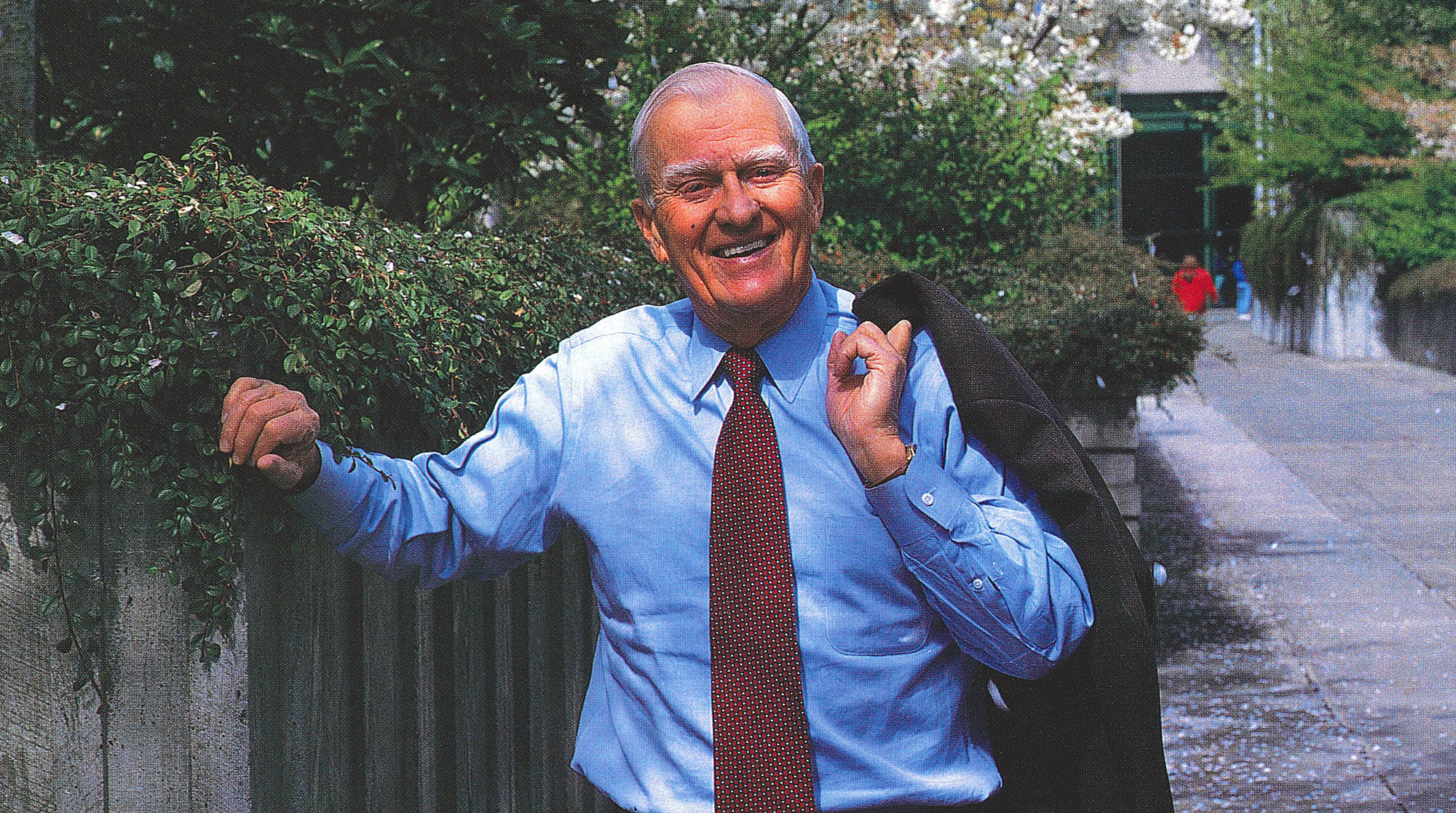

“When you think of the legacy of the Northwest,” says former Seattle Mayor Norm Rice, ’72, ’74, “and all we have — a cleaned-up Lake Washington, the green open space, even the viability of downtown Seattle, Jim Ellis’ name is at the top of the list. He truly is a visionary who has dedicated himself to bettering his community.”

For his lifetime of public service, the University of Washington and the UW Alumni Association have bestowed upon him their highest honor: the 1999 Alumnus Summa Laude Dignatus award. He joins a distinguished list of alumni who, since 1938, have been honored as the alumnus of the year. Other winners include science educator Shirley Malcom, ’67; artist Chuck Close, ’62; Nobel Prize winning biochemist Martin Rodbell, ’54; former Speaker of the House Tom Foley, ’51, ’57; and photographer Imogen Cunningham, ’08. Since the University does not award honorary degrees, it is the highest honor the UW bestows upon its graduates.

Ellis’ devotion to his community also touched his alma mater. A municipal bond lawyer with one of Seattle’s most prestigious firms, Ellis, who received his law degree from the UW in 1948, spent 12 years on the UW Board of Regents, serving as a strong, calming influence during the tumultuous years from 1965 to 1977. He played a crucial role in keeping lines of communication open with students during a time when anti-war and anti-establishment demonstrations threatened to turn the UW campus violent.

The Ellis family in 1943. From left, younger brother John, mother Hazel, younger brother Bob, dad Floyd, and Jim, then in his early 20s. Photo courtesy of Jim Ellis.

“His record of civic activism is extraordinary,” says Dan Evans, ’48, ’49, a current UW regent who has served as governor and U.S. senator. Evans appointed Ellis to the board not only because of his accomplishments, but because “I saw how he operated with people. We needed someone who could calmly listen, yet get things done.”

Ellis’ résumé is even more impressive when you consider most of his projects were controversial.

He was slammed by conservatives who considered him a communist for backing Metro, calling it a “super government,” and railing about the cost. Siting the convention center and a park on the I-5 lid drew opposition from locals who said it was too expensive and those east of the mountains who wanted the center outside of Seattle. Yet, the convention center has brought in millions to city coffers and Freeway Park, which opened in 1976, was hailed as a “first-of-its-kind” urban park by Sunset Magazine.

“Jim was always able to present arguments in such a sensible way that people believed him and joined him in the effort,” says C. Carey Donworth, a Seattle labor management consultant who worked with Ellis in the Municipal League in the 1950s. “Most of his ideas turned out to be right. And Jim was never selfish, never seeking credit or the spotlight. He got people to work together. And he made it so they would receive the credit.”

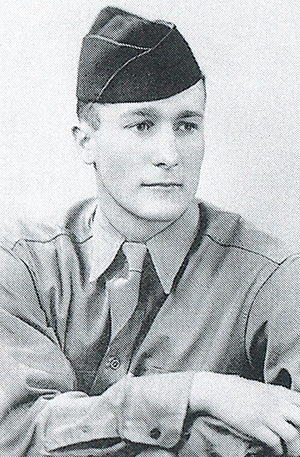

This poster encouraged citizens to vote for the creation of Metro to clean up Lake Washington.

Creating Metro, for instance, was a work of genius. Setting up a regional governing agency depended on the cooperation of all the cities in the Puget Sound area-and it couldn’t come off looking like “big-boy” Seattle was bullying them. Acting on a suggestion from his wife, Ellis convinced Seattle’s mayor, Gordon Clinton, ’42, ’47, that the smaller cities should take the lead to promote the Metro plan. After two defeats at the polls, Metro won voter approval with stunning success directly because the smaller cities publicly backed it. The citizen effort that created Metro won an All-American City Award-and Lake Washington was on its way to being cleaned up.

Ellis characteristically dismisses the idea that he’s the one who deserves the credit for Metro or anything else on the long list of accomplishments attributed to him. “It was because of friends; they are the ones who get things done,” says the now-retired Ellis, 78, from his office on the 51st floor of the Seattle’s Columbia Seafirst Center. “I only reached out to them.” His list of friends reads like a Who’s Who of Puget Sound: everyone from U.S. senators and Congressional representatives to state, county and city officials, and power brokers at major local companies like Boeing and Weyerhaeuser.

Born Aug. 5, 1921 in Oakland, Calif., Ellis, the son of an import-export businessman, grew up in California and Washington. He moved to Seattle in the 1920s, went to Franklin High School, and had the landmark experience of his early life when he was just 15 years old.

His father decided then that his two older sons (a third son John, ’52, ’53, now one of the owners of the Seattle Mariners, is seven years younger than Jim) had had it too easy. He decided they needed a wilderness experience to learn how to cut it on their own. Ellis and his brother were deposited-with a ton of groceries and two dogs-on a few acres on the Raging River (near Preston) their dad bought for $500. Their mission: build a log cabin. Oh yeah, it rained nonstop the first four days.

Jim and his wife, Mary Lou. Photo courtesy of Jim Ellis.

In three summers, the log cabin was done. Ellis still uses it to this day.

“That was a wonderful experience because I learned to do things by myself,” he says. “But it was very hard work. We had to do everything by hand, and it took much longer than we expected. We had to figure everything out by ourselves.”

The lessons learned during those summers are still paying off today. Ask anyone about Jim Ellis, and one thing everyone will tell you is that Jim Ellis always comes thoroughly prepared.

“His proposals are always so well prepared, and cover so many bases, you can’t help but agree with him,” Evans says. “He puts in so much work ahead of time, he has answers before you have questions.”

But that hasn’t kept him immune from critics who thought the lawyer at Preston, Gates & Ellis (previously known as Preston, Thorgrimson & Horowitz) was involved in public projects so be could reap financial rewards for the municipal bonds required to fund them.

“People used to think I would be sitting in my office counting money from those projects,” he says. “In reality many of the bond issues I was working on were things like sidewalks in Soap Lake, or a road in Ephrata. I was involved in public projects because it was the right thing to do.”

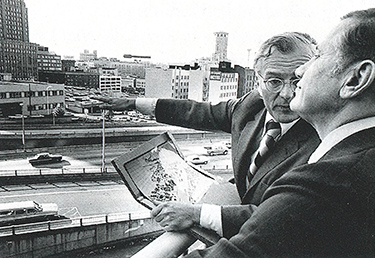

Jim Ellis lobbies U.S. Transportation Secretary John Volpe for a lid over I-5 through Seattle in 1972.

Roland Hjorth, the dean of the UW School of Law, says that trait is what really distinguishes Ellis. “He was a role model for all the lawyers he worked with not only because of his integrity, but because he was a citizen of the community,” says Hjorth, who in the 1970s spent a year with Ellis’ firm and later worked with him on municipal projects as an assistant state attorney general. “He is the exemplar of a private lawyer in public service.

“He always said for us to use our specialties for the public good. When I once remarked on the technical character of municipal bond work, Jim said his work as a municipal lawyer enabled him to participate in some of the most exciting projects of his life-projects that have improved the lives of residents of this area and that will affect the lives of residents for generations to come.”

After high school, Ellis went to Yale on scholarship but was homesick for the Pacific Northwest. He received a certificate in meteorology from the University of Chicago before enlisting in the Air Force, but when the war was over, he went to law school at the UW.

“I loved my time at the UW,” says Ellis, who with his dad watched Husky football games as a kid. “While I struggled at Yale, life was now different in law school. I was married, and we had a baby. I didn’t loaf one inch.” Indeed, he mowed lawns and worked in the law library to earn money. “But I was scared in school at first,” he recalls. “I was in a real property class, and it was like Greek to me.”

Serving as a UW regent during the 1960s, Ellis (right) raps with UW students during a student retreat off-campus. Photo courtesy of Jim Ellis.

Ellis had another unfathomable UW experience years later when he was a regent. Ellis, a veteran, personally supported the Vietnam war, and couldn’t understand why a son of his was a war protester. A serious rift developed in his family. But Ellis’ wife of 40 years-who passed away in 1983 from complications of diabetes-forced the two to work out a compromise. They did. The son decided to go into the Peace Corps, and dad and son were in good graces with each other again. That experience shaped Ellis’ term as a UW regent.

“I learned to listen to students and their concerns,” he says. “A lot of what they said had a lot of merit. We had to be open to them.” When angry students demanded to meet with some regents, Ellis and Robert Flennaugh, ’64, a Seattle dentist then serving on the board, went to a room in the HUB where the meeting was to be held. Two chairs for them had been perched on a table overlooking the entire room. “It was like we were going to be kings presiding over everyone,” Ellis recalls. He immediately got rid of the chairs, and sat on the floor, along with hundreds of students.

“If I had a list of most-admired men, Jim Ellis would be at the very top,” Flennaugh says. “He is a man of conviction, but he can get things done without running over people. He was an excellent regent because he was very active, and spent a lot of time talking with students. He was a terrific representative of the University and helped it survive a difficult period.” His calm nature serves him even at the highest levels. At a meeting in Olympia with state legislators some years back, Flennaugh became upset when a legislator who was particularly hostile toward Ellis made an offhand comment about the “dog and pony show” Ellis always put on when trying to get state support. Flennaugh, who accompanied Ellis on that trip, told him about the remark. “Later, I mentioned the comment to Jim, and he said, ‘It’s just politics. Don’t take it to heart.’ ”

He goes on. “If something is defeated, it need not be the end of the vision,” he says. “There will be another day and another chance.”

Ellis, who retired from law practice in 1991, remains as busy as ever. The man who was the visionary behind Waterfront Park, Luther Burbank Park, Marymoor Park, the Seattle Aquarium among many, many other civic projects, shows no signs of slowing down. Working nearly full time on preserving a 20-mile stretch of the I-90 corridor from Snoqualmie Pass to Puget Sound, and the expansion of the convention center, he does not see a day when he still stop using his ability to bring together disparate and conflicting interests.

“What we are working on means so much to this area,” he says. “And I think Bob would have been proud.”