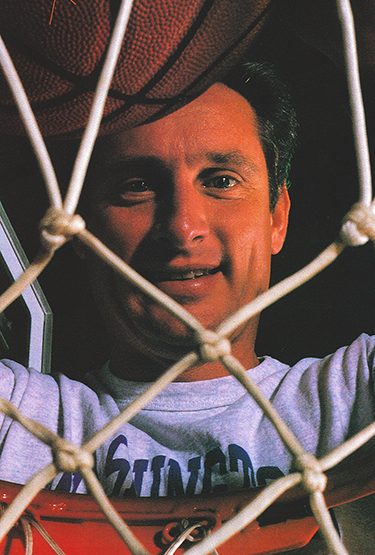

Like its coach, Husky men’s basketball team is on the rise

After six straight losing seasons, men's basketball coach Bob Bender turned a foundering UW program into an NCAA contender.

Never in a million years did Bob Bender have any intention of making a living as a coach. He was the son of a coach. When he played basketball, he was a point guard, and was considered a “coach on the floor.” Been there, done that. So when he hung up his basketball shoes for good in 1980, after a distinguished playing career, he looked for something else to do with his life—even though his genes were calling out to him and people kept telling him he would be a natural behind the bench.

Never in a million years did Bob Bender have any intention of making a living as a coach. He was the son of a coach. When he played basketball, he was a point guard, and was considered a “coach on the floor.” Been there, done that. So when he hung up his basketball shoes for good in 1980, after a distinguished playing career, he looked for something else to do with his life—even though his genes were calling out to him and people kept telling him he would be a natural behind the bench.

“I didn’t want to do that,” he says today. “I had to get away from it.”

Which sounds a little hard to believe, since he is saying this from his spacious, second-floor office in the Graves Building with the great view of Lake Washington. The sign on the door says: Bob Bender, Head Men’s Basketball Coach.

For the past 16 years—including the past five at the University of Washington—Bender has made a very nice living, not to mention quite a name for himself, as a college basketball coach. He could run from his genes, but he sure couldn’t hide.

Now he can’t hide from anyone. Though he may occasionally go unrecognized around Seattle, the college basketball world has its radar locked onto Bender. That’s only natural for someone who turned a floundering UW program with six consecutive losing seasons, into one that made the NCAA “Sweet 16” in March. During the NCAA tournament, there was just as much talk about which big-time programs would try to hire him away as there was about the upstart Husky team that unexpectedly won two tournament games and came within a rebound of upsetting No. 8 Connecticut and moving into the “Elite Eight.”

Virginia wanted him. Texas sent a private plane to bring him out for an interview. Every time a program had an opening, Bender’s name immediately shot to the top of the list—even though he kept saying he loved it here and had no intention of leaving.

Seattle suddenly found itself in March sitting on pins and needles wondering if the UW’s wunderkind hoops coach would indeed bolt for Texas, which figured to offer a bigger salary, a state with tons of homegrown talent, and a chance to hit the big time in a hurry.

But it wasn’t just the thought of losing Bender’s coaching ability that made people fret. “He’s the first coach I know that people, fans, players, administrators, even the media like,” says Marv Harshman, the retired former Husky basketball coach.

“His personality wins everyone over.”

Recalls Barbara Hedges, the UW athletic director: “I had a lot of people call and tell me to do whatever it takes to keep Bob. One of the football coaches said, ‘Whatever you do, don’t let him leave. He’s my favorite person.'”

Bender has frequently been the people’s choice. One of the nation’s top high school basketball players as a senior, he was recruited by every big-time program. He played both at Indiana and Duke, and was the first player ever to reach the Final Four as a member of two different teams. He was drafted by the NBA’s San Diego Clippers and was told that even though he wouldn’t make the team that year, he would have a chance later on. When he interviewed for coaching jobs, he usually was a top finalist.

Which is downright interesting because he wanted no part of coaching when he hung up his uniform in 1980 after a few weeks of an NBA camp and touring with an AAU team. Coaching and the game had been his whole life growing up.

“I could never get away from it,” he recalled. His dad, a former Marine, was a high school coach for 18 years in Bloomington, Ill., where Bender grew up.

(Bender, who has two younger sisters, was born in Quantico, Va., while his father was on assignment there. His dad calls his children “dollar babies” since military families only paid a dollar for deliveries.) Bender played for his father for three years–the only reason it wasn’t four, is that his dad stepped aside during Bob’s senior year to help him with the crush of recruiting.

“We were always around the game,” Bender goes on. “As a family, we were either going to my games, or my sisters’ games. And my dad always brought the game home. When I played in high school, I played for him. I couldn’t get away from the game, and I had enough.”

So when he graduated from Duke in 1980, he took his history degree like any other college graduate and looked for work. His first job: working for a financial consulting firm in Durham, N.C. He dressed up in a tie and jacket and made cold calls to companies, hoping to lure business for his firm, which went over payrolls and covered Social Security taxes for large corporations. “After six months, I decided it wasn’t for me,” he says.

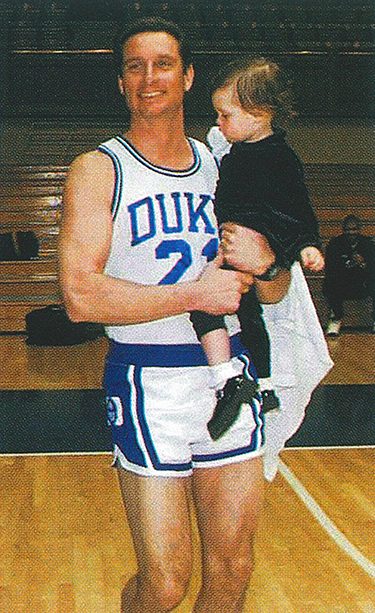

Holding his daughter Mary Elizabeth, Bender wears his old uniform at Duke’s Cameron Indoor Stadium. Bender and the Huskies visited Duke during the 1998 NCAA Tournament.

Then Tom Butters, the athletic director at Duke, needed an assistant to work in the “Iron Dukes,” the department’s fund-raising unit. Bender was his man.

He loved being back at his alma mater–where he played from 1978-1980 and helped lead the Blue Devils to the 1978 NCAA championship game. He was good at his job–both because people had fond memories of his playing days but also because of his bubbly personality. But there was one thing that bugged him. “I was involved in the atheltics but from the fringe,” he says. “And I would hear about it if the team wasn’t doing well.

“I decided then that I wanted a hands-on chance with the team.”

That chance became available when the new Duke basketball coach, Mike Krzyzewski, had an opening for an assistant. Bender applied, even though it meant going into the profession he intially shunned. Krzyzewski–who helped recruit Bender out of high school when Krzyzewski was an assistant at Indiana–loved Bender but was unsure of his motivation. “Are you sure this is something you are committed to, or are you just trying it?” he asked. Right then, Bender knew if he wasn’t committed, he wasn’t going to get the job.

In 1984, Bob Bender took his first step out on the court as an assistant. His life has never been the same. He spent six years at Duke, helping guide the team to a 164-45 record and six NCAA tournament appearances. That led him to his first head coaching job at Illinois State, a small school with a history of basketball success. When Illinois State Athletic Director Ron Wellman, who was interviewing seven candidates, met Bender, he told his staff, “We found our guy right there. He was so positive, appreciative and easy to work with. I knew he was our guy.”

For someone with no head coaching experience, Bender made an immediate impact. In his first year, Bender led Illinois State to the NCAA tournament. Two years later his team won the first of two consecutive league titles. Basketball people noticed and job offers started coming his way.

Wellman asked Bender to take a sheet of paper and list the five schools where he would like to coach someday. Georgetown, Texas, Florida and Washington were on that list.

Washington?

Well, Bender knew a lot about Washington. Not only had his Duke team played Washington twice (a 1977 regular-season game at Duke, and again in the 1984 NCAA tournament), but he also spent a lot of time in the Northwest recruiting players for Duke. The UW program, then enjoying a very successful run—including three consecutive NCAA tournament appearances—under Harshman, impressed him greatly. And he loved the area.

He couldn’t believe his stars when the UW and coach Lynn Nance parted ways after the 1993 season, opening up the head coaching job. He applied immediately.

While Bender had his sights set on coming to Montlake, Husky players had other ideas. “We decided we needed a big-name coach here to turn our program around,” recalls Scott Didrickson, who played two years under Nance. Didrickson was hoping for someone like Paul Westhead, the former Laker coach who turned Loyola Marymount into a national contender. “When we heard about Bob, I kept wondering, ‘Why are they considering that Illinois guy?'”

When “that Illinois guy” came to campus to meet the players during the interview process, “He walked up to each player and shook hands and introduced himself,” Didrickson says. “He looked us in the eye and wanted to get to know us. Then we learned of his background, too. That won us over right away.”

The players weren’t the only ones feeling that way.

“Look at his pedigree,” adds Bruno Boin, a former Husky basketball star in the 1950s and a member of the Husky Hall of Fame. “His dad is a coach, he was a great player, he played for two of the best college programs in the nation. He’s played at the highest levels and for the best coaches. He was head and shoulders above the other candidates for the job. And there were some terrific applicants.”

“He is very straightforward, no pretentions, a person of integrity,” Hedges says. “He is very friendly and charming, and he can walk into a room of totally diverse people and make every one of them feel as thought they have found a new friend in Bob. He is very intense when coaching, and he can be very emotional, especially when it comes to his players.”

Bender’s credentials were even more eye-opening. He was a member of the 1976 Indiana team that went 32-0 and won the national title. But feeling intimidated by Hoosier coach Bobby Knight—known for his tempestuous temper and explosive way of treating players and officials—he transferred the following year and landed at another A-list basketball school, Duke, where he played significantly and led the Blue Devils to the 1978 Final Four. Then, of course, came his success at Illinois State and the move to Montlake.

Good thing Bender’s senior history seminar at Duke was on Reconstruction. He was taking over a UW program that hadn’t had a winning season since 1988, saw attendance steadily decline, had internal strife, and had not been to the NCAA tournament since 1986.

First thing he did was shorten practices from 3 1/2 hours to less than two hours. He also opened practice. Anyone who wanted could drop by to watch. “If you are going to play in front of 15,000 screaming fans in a game on the line, why not in front of a few people in practice,” Bender reasons. “You have to learn to tune out distractions. And besides, we are part of the community. We want people to come watch us. Our door is always open.”

He also reinstated two players, Andy Woods and Amir Rashad, who been kicked off the team the previous season for clashes with the coaching staff. Both were named co-MVPs of the 1994 team.

But nothing could prepare Bender for that first year: the team went 5-22. “It was really tough,” says Jason Tyrus, who played that year. “And though it was so frustrating, he was so organized and positive that we knew he had a plan. Every day was something new and he kept us going when we could have given up.” Tyrus was also indebted because Bender invited him back the following year to be a graduate assistant.

Bender often had his players over to his home for dinner or a cookout, to watch a game —and get a look at the table that held his NCAA tournament watches, rings and mementoes. “I loved that the most,” says Tyrus, now an assistant at Portland State. “That left a big impression.”

The impression went further, though. Word spread about what a great motivator and teacher Bender was, how he could get in your face when you made a mistake yet have you coming away inspired and ready to try even harder.

“I know I am demanding, and I get upset,” Bender says. “But in basketball, when you make a mistake, there is nowhere to hide. Everyone sees it. I don’t want to compound a problem. You have to maintain some perspective and levity.

“When I was a player, I didn’t like it when a coach would belittle me. I learn best when someone is more positive with me.”

That made the losing more tolerable. Jason Hamilton, a Washington high school star who turned his back on the UW to play at San Diego State, transferred to the UW after two years. He wanted to come home to play—and to play for Bender, whose reputation as a coach grew despite his win-loss record.

Year two was marginally better, 9-18, but included an early season upset of Michigan, the reigning NCAA champion. Some called that victory in an otherwise meaningless non-conference game a turning point.

“That game showed us we could play with almost anyone,” says Hamilton, now an assistant to Bender. “Coach Bender didn’t let us get down despite the losing. You would think someone who has to win to keep his job would be concerned with himself but he isn’t. He wanted us to experience the same success he’s had.

“We had flashes of desperation that second year. There would be times in the locker room with tears and people feeling down, but he would come in at halftime and give us a lift and let us know he believed in us.”

One January night in 1995, Didrickson was down in the dumps. Playing for his fourth consecutive losing team, he was fed up. So 10 games into his senior season, he walked over to Bender’s Madison Park house at 10 p.m. and knocked on the door. Bender’s wife, Alice, was in bed. “He welcomed me into his home, I didn’t even call, and we sat and talked for an hour,” Didrickson recalls. “He gave me a hug and I walked out feeling so much better. But that is the kind of guy he is. That’s why his players will do anything for him.”

Bender embraced the community as well. He moved quickly to establish relationships with area high school coaches, invited them and their teams to watch Husky games, and offered to speak at high school banquets and community organization meetings. “He makes us feel important,” says Rainier Beach High School Coach Mike Bethea. “He has made such a great impression on our players.” It was one reason why the UW is now in the running for such top-drawer high school talent as Jamal Crawford, the Class AAA state player of the year at Rainier Beach, and Doug Wrenn, an honorable mention All-American from O’Dea.

Year three was the breakthrough year. “We knew we had to win,” Bender says. “It was time to produce.” With more talented players on board like Jamie Booker and Mark Sanford, the Huskies went 16-12 and earned a berth in the National Invitation Tournament. The next year was even better, a 17-11 record and another NIT berth.

Then came the magical year of 1997-98. The Huskies won 18 regular-season games and, by the hair on their chinny chin chins, were picked for the NCAA tournament (they were one the last two teams selected). The team looked like a lock for the tournament until it stumbled badly late in the season, losing six of nine conference games. But Bender rallied his team to close out the year with three consecutive victories—including a 95-94 thriller over UCLA and a 19-point victory over WSU—to make it to the Big Dance. “He focused the team so it wouldn’t lose sight of our goal,” says assistant coach Eric Hughes. “He didn’t let those losses get us down.” Finally, after five years, the team made it.

“He always was a leader,” Krzyzewski said. “He was very mature for his age, he had the ability to communicate with everyone. He loves the game, he loves the kids. I always knew he would be an outstanding head coach.

“The UW needed someone who would show the commitment and loyalty to the program there,” the Duke coach continued. “The last few years he has really made his mark.”

That mark grew during the NCAA tournament, when the lightly regarded Huskies upset No. 21 Xavier and then routed Richmond to reach the Sweet 16. The exultation, though, was bittersweet. Bender was now a white-hot commodity, considered a leading candidate at any school with an opening. After the Huskies lost a heartbreaking 75-74 decision to Connecticut, the University of Texas got very interested.

Weeks passed. Bender met with Texas officials in Dallas and in California. Tom Hicks, a University of Texas regent, even sent his private jet to bring Bender to his home in Palm Springs, Calif.

Everyone in Seattle nervously wondered if the man who had resurrected the Husky basketball program was going to leave, just like that. They knew the Texas job could provide lots of money (a salary reported to be upwards of $550,000), a huge state of homegrown talent, and a quick rise to prominence. Bender didn’t deny he was interested.

“I didn’t want to be one of those coaches who said, ‘I don’t have any interest, I don’t have any interest,” and then turns around and takes the job,” he explains.

Then came the Husky basketball banquet in April. Rumors swirled. Krzyzewzski urged him to make his announcement about his future at the very start. Bender, all 6 feet 5 of him, marched right over to Harshman, the legendary UW basketball coach from 1972-1985, and gave him a hug. That almost made the self-described “gruff” ex-coach cry on the spot. Bender announced he was staying put.

“His loyalty is what sets him apart,” Krzyzewzki adds. “Of all his traits, that is his best. His loyalty to his program, to his friends, to his players. I am his friend, and he would do anything for me. And I would for him.

“Some people become enamored of courting and lose sight of what they have right here. Not Bob Bender.”

Sure, Hedges sweetened the pot to keep Bender. But the thing Bender pushedfor hardest? Improved contracts for his staff.

“He made sure we were all taken care of,” Hughes, an assistant for the past six years, says. “That is just the type of person he is.”

Despite all the success, the media attention, the courtship by Texas, Bender remains the same energetic, positive guy, just as excited running his summer basketball camp for third graders as he is talking about the prospects for even more success next season. The Huskies will play in the Great Eight in November in Chicago against the best of the 1998 NCAA tournament field that can be assembled. And it will play in the Big Island Invitational in Hawaii in November against a tough field including Evansville, Georgia Tech and West Virginia.

“In the end, I really realized I have everything I want right here,” says Bender, who with his wife, Alice, has a 3-year-old daughter, Mary Elizabeth. They were expecting a son in early August. “Besides, I don’t want to make changes. I want to stay in one place, and enjoy the stability that it brings. The longer you are in one place, you realize how special it is.

“The people here were so patient with me, and I appreciate it. And now expectations are rising. That is what we have worked for all these years. We have credibility now. We are getting good players to come to Washington. We are a part of this community.

“And what could be better than that?”