Do pro sports pay off? Economists don’t find much reason to cheer

Pro sports' impact on the economy is closer to a bunt than a home run, but there may be other reasons to use public funding on teams.

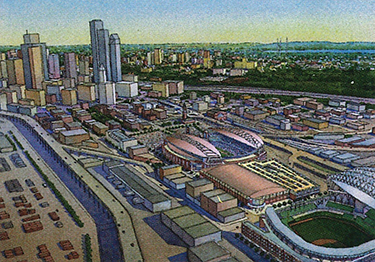

This aerial view shows a proposed open-air football stadium on the site of the Kingdome. At the bottom right is the new Mariners Ballpark, now under construction. Drawing courtesy of Football Northwest.

Hours before 74,000 people packed Husky Stadium for the UW-UCLA football game last October, UW Geography Professor Bill Beyers stood in front of 250 football fans and gave them a quiz he knew they would fail.

Beyers is an expert on economic impact studies. He’s done them on “high tech” industries, the arts, the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, and for both the Seattle Seahawks football team and the Seattle Mariners baseball team. Last fall, the UW invited him to give an insider’s view of sports economics as one of several free lectures held prior to home games.

To warm up his audience, Beyers held a “pop” quiz. “I’m going to give you three different percentages for the economic impact of sports on the local economy, and you raise your hand for what you think is the right answer,” he said.

“Ten percent.” (A good number of hands rise.) “One percent.” (A majority of hands are held high.) “One-tenth of one percent.” (Hardly a hand in the air.)

“The correct answer is 1/10th of one percent, and even that is probably overstating it,” Beyers told the crowd.

His listeners were shocked. To justify the expenditure of public money on sports stadiums, politicians across the nation have pointed to the economic benefits of professional sports.

Those arguments have been flooding the airwaves in Washington this spring, as football fans—and all of Washington’s voters—face much more than a pop quiz on professional sports. On June 17 they will be voting on a $325 million tax package to tear down the Kingdome and build an outdoor football stadium in its place. Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen has an option to buy the Seahawks, but he will drop the option if the team doesn’t get a new stadium. Allen is willing to cover $100 million of the construction cost.

The vote comes on top of a $414 million price tag for a new baseball stadium already under construction south of the Kingdome. After King County voters narrowly defeated one funding package, the 1995 State Legislature went into special session to pass a different tax package to fund construction. The ballpark is scheduled to open during the 1999 baseball season.

When asked why public funds should finance private facilities for professional sports, supporters cite economics. Football Northwest, Allen’s group advocating a new stadium, notes, “Even if you aren’t a football fan, the high level of economic activity generated by the Seahawks does affect you. Because of the revenues generated by professional football—$5.4 million are contributed to the local and state general funds—everyone benefits. The Seahawks’ total annual economic impact in Washington state is $129 million. In King County alone, the Seahawks generate $103 million per year.”

These arguments are made throughout the U.S. When Baltimore lured the Cleveland Browns with the promise of a $200 million stadium, Maryland Gov. Parris Glenening said the deal would generate 1,400 new jobs and $123 million annually to the Maryland economy.

There is a catch to economic impact numbers, cautions Professor Beyers. Often these numbers don’t reflect the true economic impact because much of the activity would stay here even if the teams moved away.

This model of the new Mariners Ballpark shows a brick facade and the stadium’s retractable roof. Some argue that sports facilities add to a community’s “public good.” Photo by Fred Housel, courtesy of NBBJ and the Washington State Major League Baseball Stadium Public Facilities District.

“If the Seahawks move to California, the local people who now spend their discretionary income to go to a Seahawks game will shift their dollars to something else,” explains Beyers. “That money stays here.”

Adds Richard Conway, ’71, co-author with Beyers of four sports studies and owner of Dick Conway and Associates, “People would likely use that money on other entertainment— bowling, the movies, whatever.”

To track the true economic impact of an enterprise—whether it is sports, the University of Washington or Boeing—Beyers and Conway look at money that comes from out of state and is spent here. Beyers calls it “new money.”

“If you yanked the business out of the region, what would be the net effect? That is what `new money’ portrays,” he explains.

Looking at new money only, the economic impact of teams such as the Seahawks and the Mariners begins to shrink. In 1995, the football team’s out-of-state revenue generated $66.7 million in local economic activity. The impact of that money amounted to 1,388 jobs in King County. The Mariners’ out-of-state funds generated only $42.9 million and 427 jobs according to a 1993 study Beyers and Conway did for the team.

“Compare this to Boeing, a corporation with 99 percent of its impact in new money,” says Beyers. “Its new money generates $25 billion in direct economic activity. The scale is totally different.” Research institutions such as the UW and Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center foster more economic growth too, since they bring in hundreds of millions in new money, Beyers adds, far more than professional sports.

Looking at the sports jobs that are created with new money, there is another hitch. Almost none of these positions are “family wage” jobs. “A major portion are day-of-game and relatively low wage jobs,” Conway says, such as parking attendants and food vendors.

“It’s not a lot of job generation,” Beyers says. There are approximately one million jobs in King County. “You don’t make public decisions about having enterprises like this in our midst on the basis of job creation.”

Neither analyst was surprised by their results, but they were jolted by the fact that the Seahawks and the Mariners are about even in attracting “new money” to Washington state, even though the Mariners play 81 homes games and the Seahawks only 10.

“I know most people are asking themselves, `What’s going on here?’ ” Conway admits. Historically Seahawks attendance per game is higher than the Mariners. Also, the average Hawks fan spends three times as much as the average M’s fan. More Seahawks fans are from out of state, boosting the new money totals for the football franchise.

The way the teams are funded also has an effect, Conway adds. Because the NFL shares national TV revenue and merchandising income to a greater extent than Major League Baseball, more new money pours into the state for the Seahawks than the Mariners. “About two-thirds of the Seahawks income is from these sources, while only half of the Mariners income comes from them,” Conway explains.

Another surprising statistic is the amount of state tax revenue that would be lost if either team left Washington. Again, the Seahawks top the Mariners, with state tax revenue from new money totaling $2.4 million annually. For the Mariners, state revenue from new money comes to $1.5 million annually. These numbers are based on general taxes, not any new taxes dedicated to building sports stadiums.

“What this means is that the state could put in up to $2.4 million per year towards a new football stadium and still come out ahead,” Conway notes. “The critical question is—`Is there justification for spending more?’ ”

“We don’t have these teams here just for the economic impact,” Beyers says. “There are other, quality of life considerations.”

Just as a community supports parks, libraries, zoos and aquariums, it should also support professional sports as a public good, say some advocates. “The Seahawks help celebrate our cultural diversity. Fans from all walks of life unite in a common effort behind our team,” notes literature from Football Northwest. “The Seahawks identify Seattle and the Northwest as a world class city and region.”

“You have to remember that the Mariners, Sonics and Seahawks are not just enjoyed by the fans in the stadium,” adds Conway. “There are hundreds of thousands of fans who watch them on TV and listen to them on the radio. Think about that enjoyment. That has a value.”

But measuring that value is close to impossible. Public Affairs Professor Richard Zerbe, an economist who does cost benefit studies, says his field defines a public good as an element the normal market system can’t value. Classic examples of public goods are pollution control and national defense, he explains.

Seattle Seahawks Quarterback John Friesz on the job. Economists say pro sports teams do not foster much job creation. Photo by Corky Trewin, (c) 1996 Seattle Seahawks.

Few “public good” studies have tried to find the value of sports, he adds. To truly measure the public good, “you’d have to track those who are not fans who would nevertheless be willing to keep the Seahawks in Seattle. How much would they be willing to pay?” Zerbe tried to interest the Kingdome Renovation Task Force into funding such a study, but the group turned him down.

“If you accept the public good argument,” Zerbe adds, “then you have to allow for some kind of public ownership. If there is a public good, why not let the public buy stock in the enterprise?”

Urban politics expert Bryan Jones, a UW political science professor recently hired away from Texas A&M, finds little in new sports facilities that contributes to the public good. “You need a common sense approach,” he maintains. “If you sat down and put together a list of priorities for this region, it is hard to believe that two sports stadiums would be at the top of the list.”

Jones says there is a “funnel” effect for public projects, especially construction of new facilities. A lot of proposals are at the top of the funnel but only a few make it all the way through to completion. “If you crowd out public projects with two sports stadiums, something else is not going to be done,” he warns.

Football Northwest disagrees. “This vote is not a trade-off. In supporting a new sports and exhibition center, voters are not saying that it is a more important expenditure for our tax dollars than education, public safety and other community services. If the governor’s plan does not go forward, the proposed sports item taxes would not be enacted for other purposes.”

Political Scientist Bryan Jones is skeptical about pro sports and the economy. For many years he has studied plant siting decisions by the automotive industry, and he says cities that outbid others for new plants never reached the economic goals they promised. “No one has ever found one economic impact statement that matches the reality once the plant is open. The estimate of tax revenue was always overblown,” he states. Jones sees many similarities in the pressures sports franchises place on communities.

Jones watched the same process go on in Houston, where the NFL Oilers threatened to move if they did not get a replacement for the Astrodome, the first domed stadium in the nation. “The mayor said the team just wasn’t worth the cost,” Jones recalls. The Oilers are moving to Nashville, Tenn., at the end of the season, but the mayor is still one of the most popular Houston has ever had, Jones says. “Houston did not fall apart as a city.”

While Jones is an outright opponent of the new football stadium, Beyers calls himself a skeptic. “It is hard to swallow doing this for a venue where a few people are making a huge amount of money,” he says.

To raise money, taxes should be paid by those who attend a game, he adds. “We do that already for the automobile with the gas tax and excise fee.

“If they can’t get construction financing based on user fees, that I don’t think there is a justification for using public funds,” the geography professor says.

Conway, who personally supports the new football stadium, does not believe economics can carry the day with the voters. “The economic benefits are not that large. If the Seahawks moved, the economy would not fall apart,” he declares.

It is not a question of economics but rather entertainment, Conway says. “The real issue boils down to this: Do we want professional sports and how much are we willing to pay for them? When we invest in stadiums, we are doing nothing more than buying enjoyment.”