Pausing the pain Pausing the pain UW doctors explore novel ways to ease patients’ pain

UW doctors turn to drugs, hypnosis and even virtual reality to ease patients’ suffering.

By Larry Zalin | Dec. 1996 issue

It was freak injury, the young man explains. While working at a local microbrewery, excess pressure in a brewing vessel blew 240-degree water across his back and legs. As soon as they saw the severity of the burns, emergency medical techs rushed him to Harborview Medical Center, site of the University of Washington Burn Center.

Five days later, he is resting in his hospital bed, greeting his visitors pleasantly. His bedclothes conceal the severe burns that run from his shoulder blades to the backs of his calves.

Burns are the most painful injuries people can have, says UW Burn Center Director David Heimbach, and the young man knows that all too well. He spent his critical first few days in the burn intensive care unit (ICU), but it is now, as he recovers in the burn/plastics unit, that pain has started consuming his body.

“I don’t know how much pain I had when I was in the ICU, because I was fully sedated,” the man recalls. “The hardest time came when I came to this unit and had to have my dressings changed. I was taking 26 mg of Dilaudid [a high dose of a strong opiate] for the intense short-term pain I was feeling then.”

To help relieve the agony, psychologist David Patterson, UW associate professor of rehabilitation medicine, is speaking with him the day before plastic surgeons plan to graft skin to the backs of both legs.

Psychologist David Patterson looks in on a Harborview burn patient. Photo by Mary Levin.

This isn’t the first time Patterson has seen the patient. When the brewery worker came on the ward, Patterson offered him another way to reduce the pain—hypnosis. Patterson carefully explained that hypnosis is not a cure but an adjunct to the pain medication the man was already taking.

Now, Patterson says, the patient is on the Pain Relief Service’s “Cadillac plan.” Because of his extensive burns, nurses must change his dressings frequently to prevent infection and aid in healing. So the patient takes Dilaudid as well as a topical anesthetic at the site of his wounds. And, 30 minutes before each dressing change, he is hypnotized to trigger a relaxation that keeps him from thinking about the pain.

“I was having a hard time during the 15 minutes it took to remove my dressings each day,” the brewery worker says. “The hypnosis calmed me—I went from a pain level of eight or nine to four or five.”

Patterson’s voice is soft and soothing as he hypnotizes the patient, and there are pauses between each number as he counts to 10. Phones ring and staff enter the patient’s room during the session, but the patient seems not to notice.

As he counts, Patterson encourages the patient to relax deeply, feel comfortable and slow his breathing. Even though part of him can hear the phone, Patterson suggests, another part only hears the psychologist’s voice.

“When you go into surgery tomorrow, you’ll have no feelings other than comfort and relaxation,” Patterson says. “The surgery is exactly what you need to make you feel better and go home sooner. You’re going to be surprised at how easily the whole procedure goes for you. You may not remember this, but maybe sometime in the future you’ll be astounded at how comfortably the surgery went and how rested and relaxed you were during the dressing changes.”

“Of all the things patients remember about their hospital stays, pain is what they remember best and for the longest time,” Burn Center Director Heimbach explains. “Pain control has been a particular concern to all of us, since the beginning of the burn center.”

Two kinds of pain are associated with burn injuries. Background pain—the pain a patient feels every day and every night—never goes away, but it’s not terrible, Heimbach says. On a scale of zero to 10, most patients rate it a three. Procedural pain occurs when a patient’s burns are washed or the patient tries to move a hand, walk, exercise or eat. This pain, Heimbach says, is always described as a 10, “the worst pain a patient has ever had or can ever imagine having.”

Little was known about burn pain when the UW Burn Center opened in 1974 with 10 beds. Helping patients survive was the first priority, and breakthroughs in clinical burn care introduced at Harborview—including an aggressive approach to wound removal and skin grafting—have reduced mortality rates dramatically.

In 1974, only half of those with burns over 30 percent of the body survived. Now 97 percent of these patients survive. Of the 450 patients treated annually, 90 percent return home within a year of their injuries, able to resume their lives.

Much of the credit can go to Heimbach, a UW surgery professor who came to the burn center in 1977. He led a multi-disciplinary effort to improve survival rates, allow people to return home to lead normal lifestyles, and reduce patients’ suffering during their recoveries.

“When we began, little attention had been paid to pain, and pain control was rather haphazard,” Heimbach recalls. “Some people still have the silly idea that patients never remember what happened to them in the ICU, so it’s not necessary to give them pain medicine. People always care about the pain they experience—if pain medicine causes them to miss some of the events of the day, we think that’s a fair trade-off for reducing their suffering.”

“Hypnosis can play an important role—for certain patients it plays a major role. There are some patients who simply don't want to take potent pain relievers.”

W. Thomas Edwards, director of Harborview's Pain Relief Service

There is a reason burn pain is so hard to control: Normal dosages of opiates don’t work very well. Opiates such as morphine work by binding to special reception points in our nerve cells. These points control the flow of information about pain going to the spinal cord and the brain, says Anesthesiology Professor W. Thomas Edwards, director of Harborview’s Pain Relief Service. When opiates bind to those cells, they slow the volume of information about tissue injuries, so patients experience less pain.

But severe burns prompt changes in body chemistry, and those changes make it more difficult to control pain with opiates. Some of the proteins in blood plasma change as the body responses to a large burn, a phenomenon almost unique to burn injuries. Opiates want to bind to this plasma protein, rather than to the usual receptors, making it necessary to give patients larger doses of medications.

As a result of such findings, burn center researchers are finding new ways to use old drugs. Spinal catheters allow medications to go where they can interact directly with opiate receptors in the spinal cord. Another approach, patient-controlled analgesia, allows patients to determine the frequency of doses of pain medication.

But the most unorthodox pain relief is delivered not in a pill or via an IV, but by a voice.

Hypnosis had been used in pain treatment for years, Patterson says, but the UW Burn Center was to first to research its use for burn patients. Used in conjunction with medication, hypnosis can decrease pain, especially for patients experiencing high levels of pain. A majority of patients who try hypnosis show some improvement, with 10-20 percent feeling dramatic results and an equal number of patients not responding significantly.

“We begin early in the day, before the patient has been medicated for a dressing change,” Patterson explains. “We often suggest that the patient imagine walking down a staircase, with each step suggesting increased comfort. Once the pattern is established, a nurse’s touch cues a patient to experience relaxation, rather than pain, during a dressing change.”

Assessing a patient for receptivity to hypnosis includes asking if he or she is willing to follow all the psychologist’s instructions. “Under normal circumstances, few people will agree to this,” Patterson says. “In the burn center, most people will say, `Sure, if it will help me get rid of this pain.’ ”

For hypnosis to work, patients have to be willing to “check out” during the dressing change, Patterson explains. Those who have to pay attention to everything that’s happening to them aren’t good candidates. Patients often need to be assured that nothing harmful will happen to them while the procedure is in progress.

Patterson began researching hypnosis during his postdoctoral fellowship at the Oregon Health Sciences Center. His interest increased when he began at the burn center 12 years ago. Patterson consulted Wilbert Fordyce, a co-founder of the UW Pain Service and a man Patterson calls “the grand-daddy of the psychology of pain control.” Fordyce suggested that Patterson pursue his interest in hypnosis with burn patients.

Today, pain control in the burn center is a team effort, according to anesthesiologist Edwards. “Knowing that Dave Patterson was here was one of the exciting things about coming to Harborview,” he says. “His reputation in acute pain-control techniques was well established. Hypnosis can play an important role—for certain patients it plays a major role. There are some patients who simply don’t want to take potent pain relievers.”

Edwards also credits Janet Marvin, a registered nurse and one of the founders of the UW Burn Center, for developing the nation’s first systematic approach to managing burn pain.

“During the early ’80s, the only papers on burn-pain management you could find were written by Janet Marvin,” Edwards says. “She instituted burn-pain rounds, where nurses talked about specific problems they were having managing their patients’ pain. Her research laid the finest of foundations to build on.”

As more becomes known about burn pain, the burn center is expanding its systematic use of morphine-based drugs, tranquilizers, hypnosis and other techniques, even virtual reality. By studying burn patients up to two years after their return home, the researchers have learned that the more pain patients feel in the hospital, the more difficult is their adjustment afterwards.

Some burn centers still refrain from using pain medications out of a concern that their patients might become addicted. But researchers at the UW Burn Center have found that patients rarely have trouble weaning themselves from pain medication. Only one in 3,000 patients becomes addicted after hospitalization. Under-medication is a greater risk, as some patients seek drugs on their own to alleviate their pain.

“I’ve never seen a patient in 20 years become addicted to narcotics after going home who didn’t have a drug problem in the first place,” Heimbach explains. “A person who’s not already addicted to drugs wants nothing more than to get rid of them—patients don’t like feeling spaced out, and they don’t like feeling as though they don’t have control.”

Current pain research includes focusing on children, who comprise a third of the UW Burn Center’s patients. Children now receive drugs on a regular schedule, rather than waiting until they say they hurt. Young patients don’t mind receiving fentanyl, a fast-acting synthetic morphine, that can now be delivered orally rather than intravenously.

“Despite all our efforts, I think we’re still ahead in the clinical area—getting the patients covered with healthy skin and able to go back to school or work—than we are in our efforts to control their pain,” Heimbach says. “We still have a long way to go in terms of pain control.”

“If it works, we’ll use it, provided it’s safe and effective,” says Edwards. “One thing we do especially well is to combine approaches, using many kinds of specialists. Physicians, nurses, psychologists, physical therapists all pull together and work as a team. A huge amount of research goes on here, and we’re clearly ahead of the pack.”

Mind over matter—virtual reality and pain control

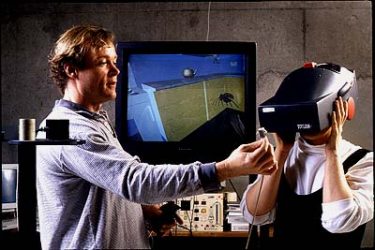

UW Researcher Hunter Hoffman demonstrates a virtual reality helmet that may someday help burn patients.

Virtual reality may also play a role in helping burn patients alleviate their pain. Some dentists already use virtual reality with their patients, and children viewing cartoons through TV “glasses” have been reported to experience less pain and fear.

Now researchers at the UW Burn Center at Harborview and the UW Human Interface Technology (HIT) Laboratory have joined forces to see if virtual reality can also temporarily distract burn patients from experiencing pain.

“Pain requires conscious attention,” says Hunter Hoffman, a research scientist at the HIT Lab. “An attention-grabbing, 3-D, interactive computer-simulated environment may help these patients by allowing them to focus on something other than their pain.”

Patients in the burn center will soon have the chance to wear virtual reality glasses to experience new worlds. They may explore a shipwreck on a shark-infested ocean bottom, create a building-sized atom, or navigate their way through a fully furnished virtual house.

The interdisciplinary research team is reasonably confident that offering patients virtual reality will reduce their subjective intensity of pain during dressing changes. If patients respond favorably to these informal virtual reality tests, empirical studies will soon follow.