Good sports Good sports UW psychologists show sportsmanship is a winning strategy

Two UW psychologists are teaching players and coaches how to play the game, no matter who wins or loses.

Two UW psychologists are teaching players and coaches how to play the game, no matter who wins or loses.

Ron Smith and Frank Smoll are the ultimate good sports. For more than 20 years, the two UW psychology professors have been laboring to banish tyranny, anxiety and stress from America's playing fields. Their goal is to replace those negatives with an athletic atmosphere that fosters fun and learning in a positive and fear-free environment.

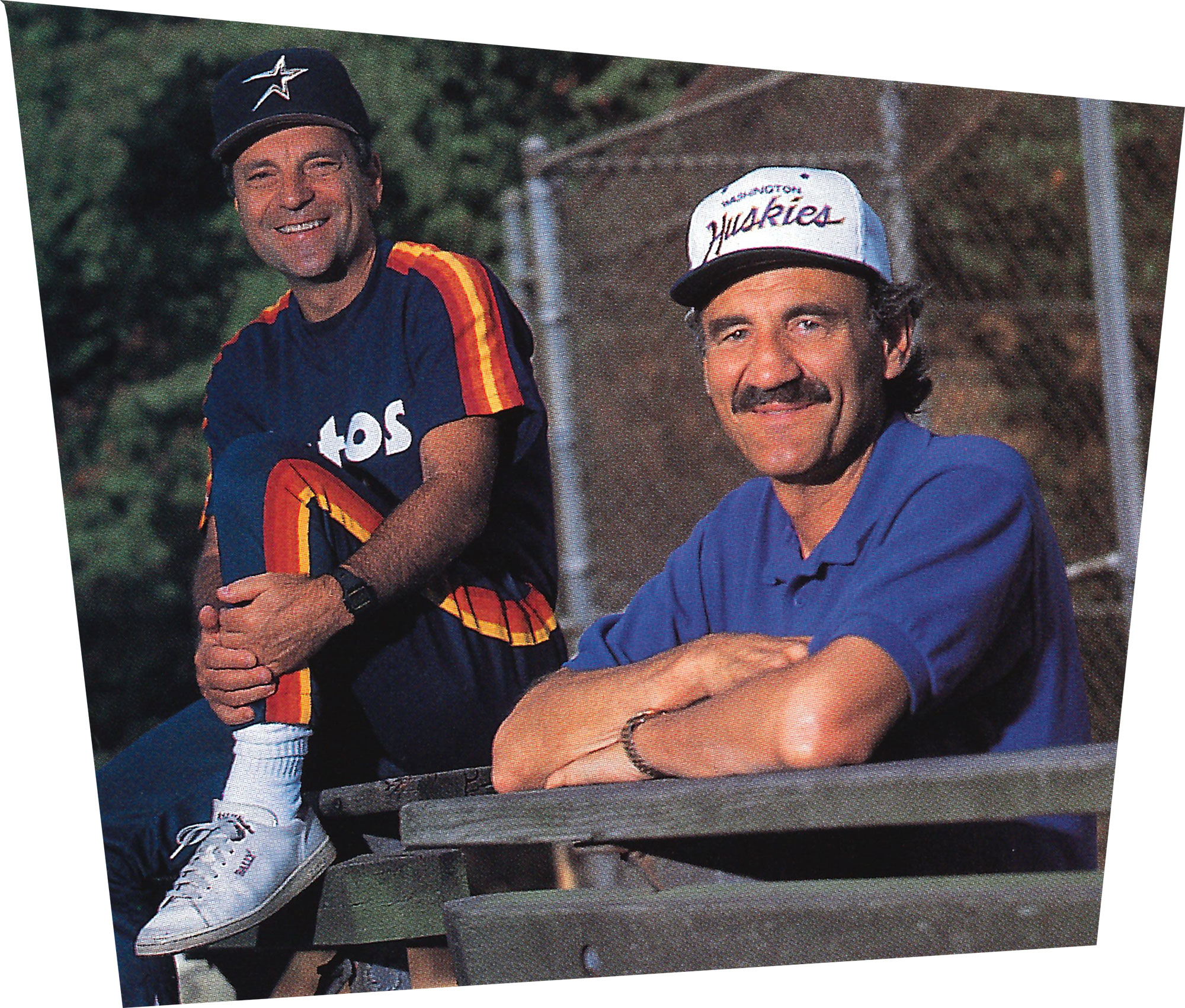

That may sound Pollyannish in today’s world of multimillion-dollar contracts and choleric coaches like Billy Martin, Woody Hayes and Bobby Knight, but when Smith (pictured at left) and Smoll (right) talk, people listen. From Little League to major league, from athletic fields of the Catholic Youth Organization to Husky Stadium, the pair is changing the way people play many of America’s pastimes.

Their target is not always the players themselves, but also the coaches. Through a Coaching Effectiveness Training (CET) program, Smoll has influenced the style of more than 10,000 youth coaches at more than 200 workshops. The secret of CET is simple. It teaches coaches to emphasize praise and encouragement for effort as well as for performance.

“Winning is more important to adults than it is to children.”

Frank Smoll

“Having a good time is more important to kids than winning,” says Smoll. “Winning is more important to adults than it is to children.”

The same coaching techniques can apply to the pros. Smith is a traveling instructor with baseball’s Houston Astros. The professor wrote a psychological skills manual used by the club and its minor league farm teams. When the Astros and their minor league prospects go to spring training, or when the team holds a camp for its summer instructional league, Smith sets up his office in left-center field. With the help of the Astros, he’s also trying to find the psychological, emotional and physical skills that can predict which players eventually will make it to the majors.

The Astros have more than a casual interest in this work. Averaging the cost of its minor league system, the ballclub estimates it spends $2 million for each minor league player who makes it to the majors. Throughout baseball, the number of players who wind up in the major leagues after signing a pro contract is small, only between 3 and 5 percent. The Astros, with a more psychologically sophisticated approach to developing young players that Smith helped create, have raised their number to 9 percent.

Smith and Smoll also are familiar figures around the Husky athletics department. They’ve been working with individuals and teams since 1974 when they helped a “Wednesday All-American” overcome his game-day fears on the football field. In addition, Smith and Smoll co-authored The Parent’s Complete Guide to Youth Sports with Nathan Smith, UW professor emeritus of sports medicine and pediatrics.

The core of Smith and Smoll’s work with the pros stems from their research into youth sports. “I use the same CET principles with the Astros coaching staff as I do with little league coaches. They can be used at the major league level in teaching players,” says Smith. “With the Astros, some of the things we are teaching are life skills, such as how to manage stress, develop action plans and learn attention skills.

“What we are really dealing with is human performance enhancement. There are all kinds of applications for it.”

Ron Smith

“Sports is a wonderful environment in which to teach these skills, which extend beyond sports to all aspects of life. What we are really dealing with is human performance enhancement. There are all kinds of applications for it.”

The UW psychologists have found that youth coaches can play a significant role in the lives of young players, one that extends beyond the playing field.

“Coaching is a leadership position that has a tremendous impact on all young athletes,” explains Smoll. “Today, with so many single-parent families, a coach may occupy the role of a parent. This even may be true in a two-parent family because kids very often turn to coaches for help.

“Coaches are of paramount importance. Their relationship with a child will set up the framework of relationships with future coaches. It is a foundation for building or destroying future trust, not only with coaches but with all authority figures. Usually coaches are overly concerned with teaching the skills of the sport and not with understanding and developing a relationship with the child. They are focused on the sport, not the child. Adults often don’t realize what a potent role they occupy and what they do can have a long-term impact that goes way beyond sports.”

For instance, Smith and Smoll have found that coaches can damage or improve a youngster’s self-esteem, decrease or raise a child’s level of performance anxiety, and most important, are a crucial factor in whether a player will continue to participate in sports.

All of this work stems from a modest start back in the early 1970s. Smith, whose major areas of research are stress and coping with stress, became interested in coaching youth sports along with another UW psychology professor. When his original collaborator decided to pursue other academic interests, Smith teamed up with Smoll, who then had an appointment in kinesiology.

It was the beginning of a fruitful association that’s now in its third decade. Both have had experience coaching. Smith worked his way through Marquette University as a coach for the Milwaukee County Parks Department. Small coached his son’s baseball team and also was an assistant high school and college baseball coach.

Smith and Smoll organized the largest behavior assessment ever done in sports psychology, recording and categorizing 57,000 separate coaching behaviors.

When they began their collaboration, there was little empirical data on coaching youth sports. Although it was suspected, no one had proven that a pat on the back was more effective than a kick in the butt. So Smith and Smoll organized the largest behavior assessment ever done in sports psychology, recording and categorizing 57,000 separate coaching behaviors. To gather this data, they and their students tracked the behavior of 51 baseball, basketball and soccer coaches at 202 games over a three-year span. They defined a coaching behavior as some type of interaction such as a coach crying out, “Way to go!” when a youngster gets a base hit or a coach throwing his hands up in the air and frowning when a player misses two free throws.

The researchers interviewed 542 players to gather the youngsters’ reactions to the experience and their coaches. Smith and Smoll wanted to see how specific coaching behaviors influenced the youngsters’ attitudes toward their coach, their self-esteem and their sport.

After analyzing mountains of data, Smith and Smoll designed the prototype for CET, a training program for coaches that stresses a positive approach to sports. This supportive style of coaching asks adults to praise good effort and performance and to respond to youngsters’ mistakes with encouragement and technical instruction rather than with criticism and punishment.

Then they went back to the playing fields to see if it worked. Thirty-one coaches and 325 players were divided into two groups. One was taught how to use the new program while the other had no special help. The UW team monitored practices and games and again questioned young participants about their experiences at the end of the season.

On the scorecard, CET made no difference. The average won-loss records for both groups were similar. Yet the CET coaches were hands-down winners compared to the untrained coaches. They were better liked and rated better teachers by their players. These players also reported greater enjoyment from the sport than did the youngsters under untrained coaches. Players coached by CET-trained adults also said they experienced less stress and performance anxiety.

In 1989, a follow-up study of 152 Seattle-area Little Leaguers showed similar positive reactions. Most significantly, the dropout rate for players under CET coaches was only 6 percent the following season. The control group had a 26-percent dropout rate the following season. Nationally, youth sports dropout rates from one season to the next can be as high as 40 percent.

Over the years, the UW professors have spread the word about CET at workshops and clinics for youth coaches throughout Washington, Oregon, California, Colorado, Wisconsin, Michigan, Illinois and Canada. Smoll also has taught workshops for junior and senior high school coaches in Washington, Alaska and Illinois.

Organizations which have used or sponsored their workshops swear by it. “CET workshops are required for all of our first-year coaches,” says Frank Cammarano, athletic director for the Catholic Youth Organization, which runs programs for 12,000 boys and girls in the Puget Sound area. “Frank and Ron have worked with literally thousands of coaches for us and they are basic to our program. They take our training to another level.”

* * *

A new booster of the program is the Washington Council for the Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect, which cosponsored a CET workshop with the Little League organization in Vancouver, Wash., last spring. The workshop was so well received that the council is planning five more in Walla Walla, Wenatchee, Yakima, Port Angeles and Seattle in time for the football and soccer seasons.

Joe Superfisky, who was the administrator of the greater Seattle Little League district when CET was tested in 1989, is another vocal backer.

“The feedback from our coaches was fantastic. The training is entertaining and very informative. There is much more to coaching Little League than hitting and running. Young minds can be easily damaged. Just changing a few words or the tone of your voice can make a big difference. I’d like to see this training used in football, soccer and with PE teachers. Anyone working in youth sports would benefit from it.”

Others, particularly the Huskies and the Astros, certainly are better off. The pair’s ties to Husky athletics are more than 20 years old, dating to when Jim Owens was coaching football. Back in 1974, Smith was researching stress management and was looking at students with high levels of test anxiety. One of his research subjects was a football player who was leaving his best performances on the practice field. That ended when he began applying what he learned about taking tests to his performance on game day.

After the player told Owens about Smith, the coach contacted the psychologist, initiating a relationship that has continued through the regimes of Don James and Jim Lambright.

The ties between the athletics and psychology departments have become stronger since Barbara Hedges became athletics director. A raft of programs under the umbrella of Husky Sport Psychology Services has been created with guidance from Smith and Small. These include funding for two psychology graduate students who conduct a variety of workshops and a series of three-day programs covering aspects of mental toughness.

Funding from the program also supports teaching assistants for a new course, Psych 201, “Human Performance Enhancement,” which may be the first campuswide class offered with the financial help of the athletic department.

“There is a constellation of psychological skills that tends to be characteristic of successful people and maximize achievement in business, science, sports or any field,” says Smith. “You are not born with these skills, but you can learn them and our goal is to help students acquire them early in their academic careers.”

“A lot of why people fail in baseball is mental. There is something that separates people from others.”

Fred Nelson, Houston Astros director of minor league operations

Smith also is teaching these skills to players in the Astros farm system, which employs three psychological experts. “We really believe the psychological program is important,” says Fred Nelson, director of minor league operations for the Astros. “A lot of why people fail in baseball is mental. There is something that separates people from others. The separation comes from those who are mentally tougher, can relax, and have taken on such skills as visualization, goal setting and the ability to focus their attention.

” … Even if the program only works on 5 percent of the players, we are still ahead down the road. At our camps, Ron will broadly introduce our psychology manual to our new players and explain why it’s important. We don’t make a big deal out of it because we throw a lot of material at the players. For many players this may be their first time away from home or their first exposure to the idea of psychological skills. As they begin to mature, they become more open to the program and they realize that it is not witchcraft,” Nelson explains.

Working with young athletes is how Smith and Smoll got started in sport psychology. They still have work in that field they’d like to accomplish. The pair would like to see youth sports programs expand in America’s inner cities and are interested in training coaches for major league baseball’s new RBI (Return Baseball to the Inner city) program. RBI tries to attract black youngsters, who now favor basketball and football, back to baseball. Smith and Smoll also are interested in girls’ athletics. They want to design research that is specific to girls’ sports to see if the same principles that they’ve developed for coaching boys apply.

“Ron and I both have admiration and respect for the good job most youth coaches are doing,” says Smoll. “We don’t have rose-colored glasses on and realize there are problems. But most youth coaches really want to teach children and their job is tougher than that of a high school or college coach. It’s because of the range in the maturity of the kids they are dealing with, and because teaching the foundation of a sport takes so much time.

“Our CET workshops are the most satisfying thing I do as an educator. I have the dual roles of both a scientist and a teacher. The workshops allow me to take our science to the public and teach it.”