Calling the shots Calling the shots William Foege, ’61, honored for his role in eradicating smallpox

The 1961 graduate who helped banish smallpox from the planet is the 1994 alumnus of the year.

The 1961 graduate who helped banish smallpox from the planet is the 1994 alumnus of the year.

In 1979, smallpox vanished from Planet Earth due, in part, to a shortage of vaccine and a persuasive American doctor.

That year, the World Health Organization verified that, for the first time in history, humanity was able to stomp out forever an infectious disease. A turning point in that campaign was a 1966 incident in eastern Nigeria.

A medical missionary, Dr. William Foege, was part of an effort to inoculate the people of West and Central Africa with smallpox vaccine. A shipment for mass vaccinations was due in a few months, but smallpox didn’t wait.

Foege got a radio message that an isolated village had a smallpox case. Could he come and verify the outbreak? “The village was seven or eight miles from a road. It was smallpox all right, but we did not have sufficient supplies and we were not going to get supplies to vaccinate everybody.

“That night we sat around and asked ourselves, ‘What would we do if we were a smallpox virus bent on immortality?’ ” Foege recalls.

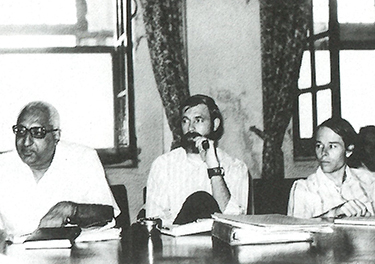

Left: Foege (center) confers with health officials in 1974 over the smallpox epidemic in India. In one week, 10,000 cases were reported, but in less than a year the disease was wiped out. Below: A smallpox victim from Zaire. Photos courtesy of the Centers for Disease

The medical missionary resorted to military tactics. He spread out maps of the district. He asked a ham radio network of missionaries to seek out any cases.

“In 24 hours we had reports of every village with smallpox,” he says. “Our first priority was to use vaccine in those villages—there were only three or four at first. Then we asked ourselves where would smallpox go, and followed the family and market patterns.”

Smallpox has an incubation period of up to 14 days. Foege called the shots, inoculating market villages and places where relatives of the first victims were living.

When the disease broke out in those secondary locations, the rest of the population was already protected. “Four weeks later, there was no more smallpox.”

Health authorities thought they needed to inoculate 80 to 100 percent of the population to stop smallpox. Foege was able to stop the disease with less than 50 percent. Through “surveillance” of the outbreaks and “containment” of the disease, the epidemic was stopped in its tracks, months before the shipment for mass vaccinations finally arrived.

Foege became an apostle of this good news, but the new technique, (eventually named “surveillance/containment”) was a hard sell. Sent by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to stamp out smallpox in parts of Africa, many field workers considered Foege’s idea a “typical, cracked-brain headquarters scheme, completely out of touch with reality.”

But Foege, back at the CDC headquarters in Atlanta after civil war engulfed Nigeria, pressed his case. “Bill has a great talent for coming up with creative ideas and presenting them in a way that doesn’t threaten people,” says William Watson Jr., who was then deputy director of the CDC.

A skeptical CDC doctor in Sierra Leone, Donald Hopkins, decided to give surveillance/containment a try. The West African country was one of the most heavily infected nations in the world. Within nine months, with less than 70 percent of the population vaccinated, smallpox had vanished.

As the architect of a radical vaccination scheme, and an unrelenting advocate of the idea, he helped banish the scourge from the Earth.

Surveillance/containment soon became part of the worldwide vaccination campaign. On any list of that effort’s “heroes,” you’ll find the name of Bill Foege. As the architect of a radical vaccination scheme, and an unrelenting advocate of the idea, he helped banish the scourge from the Earth.

Playing a pivotal role in smallpox eradication is one reason why Foege, a 1961 graduate of the UW School of Medicine, has been named the 1994 UW Alumnus Summa Laude Dignatus. The award is the highest honor the UW can bestow upon its graduates.

The U.S.—and the world—is a healthier place thanks to his efforts. As head of the CDC from 1977-83, Foege (pronounced FAY-gy) reorganized his agency, putting more resources into preventative medicine. During his tenure, the CDC was able to pin down quickly the cause of two major health crises: toxic shock syndrome and Reye’s syndrome in children.

In his post-CDC career Foege has set his sights on destroying three more diseases: polio and two parasitic scourges, river blindness and Guinea worm.

Two presidents have asked Foege for his help. In 1986 former President Jimmy Carter invited Foege to become the executive director of the Carter Center in Atlanta, a position he held until last year. “He provided leadership for a broad array of international programs addressing issues of human rights and conflict resolution throughout the world,” Carter said.

President Bill Clinton recently nominated Foege to be executive director of UNICEF. Foege is one of five nominees; a decision by U.N. Secretary General Boutros Boutros-Ghali is expected in October.

The globetrotting Foege is the son of a Lutheran minister. He grew up in Chewelah and Colville in the far northeast corner of Washington.

With four sisters and a brother, it was a close-knit family, Foege recalls. His older sister, Grace, had a particular influence on him, blazing a trail to Pacific Lutheran University in Tacoma and then the UW medical school, a trail which her brother followed. Always interested in Africa, Foege applied to medical school in the hope of using those skills on that continent.

UW Physiology Chair Wayne Crill was a housemate during Foege’s first two years in medical school. Foege is 6 foot 7 inches and Crill had the same response everyone else does on first meeting. “My reaction was ‘Gee that guy is tall,’” Crill recalls.

* * *

Foege quickly earned the reputation as a practical joker, one he carries to this day. But as his classmates got to know him, one quality stood out, adds Crill. "He was clearly interested in those aspects of medicine that were not the money-making, flashy aspects. Always, always."

Planning to become a medical missionary, Foege concentrated in public health, which led him into contact with Dr. Reimert Ravenholt, then the King County public health officer. “He was an intriguing professor,” Foege recalls, “who made public health much more interesting than it would be otherwise.”

Fresh out of medical school, Foege joined the CDC’s Epidemic Intelligence Service. In 1965 he earned his master’s in public health from Harvard and then headed for Yahe, Nigeria, to start a medical mission for the Lutheran church.

“We lived in a village in Africa with no electricity, no running water, in a mud hut with a 3-year-old boy. That’s not easy,” he says. Foege was fighting smallpox across eastern Nigeria when one of that nation’s states—Biafra—declared its independence. Civil war broke out in 1967 and his family was evacuated.

Foege stayed, though times were dangerous. Once he rescued a fellow health worker who had been held at gunpoint by a 13-year-old rebel. Foege himself was placed in detention twice, once for several days. To attend a conference in Ghana, he had to canoe across the Niger River. He never went back.

President Jimmy Carter (left) and William

Foege confer at the Carter Center. Foege was

executive director of the center for seven years. Photo courtesy of the Carter Center.

“There were things that made you wonder what you were doing there. I remember thinking, ‘Medical school wasn’t ever this hard.’ ”

With his mission in ruins, he returned to the CDC, working his way up to become head of the Smallpox Eradication Program. One U.N. official asked that the CDC “loan” Foege to tackle the problem in India. But some of his colleagues urged him not to go. “You don’t need a failure like that on your record,” one warned. Then-CDC Deputy Director Bill Watson recalls a “very senior World Health Organization official” telling him and Foege, “If you eradicate smallpox from India, I’ll eat the tire off your jeep.”

After Foege arrived in India in 1974, the epidemic actually started to worsen. In one week in the state of Bihar, more than 11,000 cases were reported, resulting in up to 4,000 deaths. “The number of cases reported went up,” recalls Watson. “It really dismayed people. There was a lot of second guessing. The pressure was on to do it the old way; this new system isn’t working.”

Foege says he couldn’t convince the minister of health to stay with surveillance/containment. At a meeting the minister was prepared to order mass vaccinations when an Indian physician stood up. The physician recalled growing up in a poor village. When there was a fire, the villagers poured water on the burning hut, not on all the houses, he said.

“The minister was stunned. ‘I’ll give you one more month,’ he told us,” Foege says. In that month rates finally started to go down.

Foege says that unknown physician is the hero of the Indian eradication campaign. Watson says there’s more to it than Foege is willing to admit. “I think Bill’s major contribution was in the operational side,” Watson says. “He convinced them to stick to it and see it through.”

Of the international effort to curb smallpox, Foege says, “It was one of the greatest professional experiences of my life. The heady time was in the ’60s, when we could visualize eradication and see the prophecy come true.”

Twisting around the old proverb, he adds, “Some things have to be believed to be seen.”

By May 1975, the disease was in retreat. Foege returned to Atlanta as assistant to CDC Director David Sencer.

The CDC’s reputation—spotless compared to most government agencies—suddenly slipped into the barnyard over the swine flu vaccine fiasco. Sencer recommended mass vaccinations against an influenza strain (swine flu) thought to be the mass killer of the 1918-19 pandemic.

More than 50 million Americans received flu shots, but cases of a rare, polio-like disease called Guillain-Barre syndrome suddenly cropped up. The vaccine was pulled and public health officials—especially Sencer—were blamed for overreacting.

Months later, when President Jimmy Carter appointed Joseph Califano to head the Department of Health and Human Services, Sencer’s days were numbered. “It is accurate to say that Califano fired Sencer. I am convinced in my mind that swine flu was part of that,” recalls Watson.

“When you talk to Bill Foege, you find he is very approachable, solid, a deep thinker.”

Physiology Chair Crill

CDC staff feared that politics would take precedence over public health. At first, Watson says, Foege didn’t have much of a chance with the new health secretary. “I don’t think he intended to appoint someone from within the CDC to follow Sencer. We played for at least getting Foege interviewed, and then Califano was taken with him like everyone else.”

“He is not a shrinking violet,” adds Physiology Chair Crill. “When you talk to Bill Foege, you find he is very approachable, solid, a deep thinker.”

In his six years at the head of CDC, Foege completely reorganized the agency. “We did it so that when you have a problem to solve, you are organized to meet that particular problem,” he says. “We’re going to keep finding new diseases forever, that is, new organisms, new expressions of old organisms, or a combination of sociological factors and new organisms, such as with AIDS. We must be prepared to face new infections.”

As director he faced three major health crises. In 1980 women started experiencing a high fever, low blood pressure, rashes, vomiting and diarrhea. With the help of state health departments, the agency was quickly able to trace the cause—toxic shock syndrome, stemming from a new brand of tampon. Procter and Gamble immediately pulled it off the market.

A different industry was not as cooperative when the CDC began to link aspirin with Reye’s syndrome in children suffering from flu or chicken pox. Reye’s syndrome is a rare disease that kills about 40 percent of its victims and leaves others brain-damaged.

In 1981 CDC workers picked up the link in four or five studies, but each individual study was too small to show statistical validity. “We couldn’t prove it statistically yet, but there was no question that this was valid,” Foege recalls.

The aspirin industry launched a full-scale attack on the studies. Foege wanted a warning printed on all aspirin bottles. He was backed up by the secretary of health, but the Reagan White House insisted on another study first. That study confirmed the link and warning labels finally appeared on bottles in 1986.

“Politics still got involved in public health. I did not stay much longer,” Foege says of that time.

But before he left, the man who helped stamp out one disease, smallpox, witnessed the birth of another—AIDS.

In the summer of 1981 reports of young men with rare pneumonia or a rare form of skin cancer—Kaposi’s sarcoma—trickled into the CDC. “We didn’t know what it meant. But it didn’t take long to realize that this was bigger than we expected,” recalls Foege.

“It was a steam roller that just got bigger and bigger and you couldn’t imagine it could get worse and worse. There was nothing like it on this scale. You have to remember that there not many things that are 100 percent fatal beyond rabies. AIDS just did not follow the rules in any way,” Foege says.

When the CDC sounded the alarm, others remained skeptical. “We couldn’t get anyone else to listen: politicians, blood banks, media. It was just so bad that people didn’t want to believe it,” Watson says.

“I’ve found that there is an incubation period for ideas as well as for viruses,” Foege adds.

“We used existing resources, mostly from the VD program itself. There was no extra money, no relevant articles in peer publications, very little press for a year and a half,” Watson recalls. “It was a frustrating time.”

Though critics often complain about the lack of money devoted to AIDS, Foege points out that line items on budgets often don’t reflect the reality of those times. “A lot of research dollars got directed early on,” he says. “But even that wasn’t enough.”

Foege is particularly proud of publishing some of the first prevention information about AIDS, before it was conclusively proved that a virus caused the disease. The CDC “printed what we knew, and what we knew about prevention, back in 1983. And it is still valid today.”

Asked if someday AIDS will be stamped out the way smallpox has been, Foege responds, “I cannot imagine that we will not ultimately find a preventive vaccine. That’s the direction we’re going.”

A believer of things not yet seen, Foege has concentrated on destroying three diseases since he left the CDC in 1983.

He is the head of the Task Force for Child Survival and Development, which has raised the general immunization level of the world’s children from 20 percent to 80 percent in six years. Among its goals is the eradication of polio by the year 2000.

The task force has also targeted river blindness (onchocerciasis), a leading cause of blindness in Latin America and Africa. Thanks to a free supply of a drug furnished by Merck & Co., about 9.5 million people will be protected by the end of the year.

In 1986 President Jimmy Carter asked Foege to take over as head of the Carter Center. “President Carter was very interested in international public health and he convinced me that it would be a good place to be,” Foege says.

As part of the center’s Global 2000 program, Foege hopes to knock out yet another disease by the end of 1995—Guinea worm. A parasite found in stagnant water, the worm can grow two to three feet long within the body, causing secondary infections, scarring and crippling similar to polio.

To combat the disease, Global 2000 uses surveillance/ containment. In four years cases decreased 90 percent in Ghana and Nigeria. Pakistan is expected to be completely free of Guinea worm by the end of the year.

Foege recently stepped down as Carter Center director. Still a fellow at the center, he wants to spend more time on health programs. He may get his wish in spades if the U.N. secretary general taps him to head UNICEF.

“This is the only job in the world he would leave what he is doing now to take,” says his long-time colleague Watson. “He’d be able to make an impact on the welfare of the children of the world.”