Voices from the past filter into Tami Hohn’s classroom as her students listen to oral recordings in Southern Lushootseed. Punctuated by cracks and hisses, the aging audio brings to life the words of first-language speakers captured decades ago—when there were many more of them.

The sounds and stories preserved in those recordings are connecting across time with a new generation of speakers at the University. Guided by Hohn, students learn to follow a trail of linguistic clues to unlock the indigenous language of the Puget Sound.

In 2019, thanks to Hohn’s work and the Department of American Indian Studies, Southern Lushootseed officially joined the more than 60 world languages already taught at the UW. The full-year course, which is on its way to becoming a permanent part of the curriculum, gives students the ability to excavate the language from the writings, recordings, cultural practices and land where it’s been preserved.

Southern Lushootseed permeates the land around the University of Washington, from the texts and archives held at campus libraries to the names of geographical features like the Duwamish River and the Kitsap Peninsula.

“There’s a language held in this University,” says Hohn, a UW lecturer and Puyallup tribal member who has dedicated much of her life to sharing the language. “If I can teach people how to find it and use it, it will spread everywhere.”

Lushootseed, which has distinct Southern and Northern dialects, was once spoken widely by the Coast Salish peoples, from the Skagit Valley to the inlets of the southern Puget Sound. Centuries of genocide, disease and forced assimilation policies took their toll on the numbers of first-language speakers.

In the 1960s, a small group of scholars and community members started interviewing and recording first-language speakers. Many Lushootseed resources wouldn’t exist today without the work of Upper Skagit Tribe member Vi Hilbert and UW linguist Thomas Hess, who collaborated over four decades to document, preserve and standardize Lushootseed as a modern language. Hilbert taught Northern Lushootseed at the UW for many years until her retirement in 1988.

“The magnitude of work in the past has made our work today that much better and more effective,” says Hohn, adding that the documents and recordings from first-language speakers are invaluable to today’s learners.

Building on that work, the Puyallup, Muckleshoot and Tulalip tribal schools have infused Lushootseed into the daily curriculum. It was at the Puyallup tribe’s Chief Leschi School that Hohn first formally encountered Southern Lushootseed, as a culture teacher in 1993. A summer workshop with a respected elder and first-language speaker sparked Hohn’s quest to learn the language embedded in her DNA—and share what she learned with her students.

“I spent a lot of years just building my knowledge of the grammar,” says Hohn. “It took a long time for me to piece that together, and because of those struggles, that’s my priority in teaching.”

Resources in Southern Lushootseed—from oral recordings to anthropological field notes to folk tales—are spread throughout the region, requiring students of the language to become linguistic detectives. Hohn’s first-year course is designed to give students the tools to decode the language—and use those skills to follow the trail, wherever it may lead.

“My goal for these students is that they become lifelong learners,” Hohn says. “They know how to research. If they don’t know what the sentence is saying, they know how to figure it out.”

That journey progresses twice a week in a small classroom, where Hohn’s 15 beginner students eagerly set out notebooks and dictionaries on L-shaped desks. Eventually they’ll create conversations and analyze stories, but they start with the basics: the 42-character alphabet and the root words that are Southern Lushootseed’s backbone.

“If we want this to be a world language, we have to set it free. We have to allow it to be spoken and taught by everybody who’s interested.”

Tami Hohn

Every word in Southern Lushootseed, whether spoken or written, is packed with information. Root words—verbs like “to see” and nouns like “water”—are transformed with suffixes and prefixes added to show action, possession, location or intent, creating an impressive variety of vocabulary words to unpack.

There’s no conventional textbook. Instead, Hohn scours many sources—folk stories, recordings, research—for relevant grammar and vocabulary.

Toggling between Times New Roman and a special Lushootseed font on a projected screen, Hohn asks her students to dissect the words in a Lushootseed phrase that means “Who are you?” The class is hushed as students thumb through their Lushootseed dictionaries, flipping pages written decades ago, to find the right root words.

Beyond giving students a solid foundation in the grammar, this exercise prepares them to be language treasure hunters who can piece together linguistic clues with cultural context.

Asking someone in Southern Lushootseed who they are, for example, is posing a question that goes beyond the superficial into someone’s family background and lineage.

For Southern Lushootseed to thrive again in the Puget Sound it needs a diverse set of speakers. The course attracts both Native and non-Native students from a variety of disciplines; many bring experience with other languages.

“If we want this to be a world language, we have to set it free,” says Hohn. “We have to allow it to be spoken and taught by everybody who’s interested.”

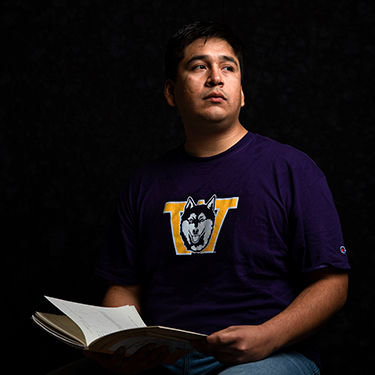

Victor Andy, one of Hohn’s students, grew up surrounded by the sounds of the Yakama language in White Swan, a small town east of the Cascades in the heart of the Yakama Indian Reservation. An English major fascinated by linguistics, Andy, ’20, discovered an affinity for Southern Lushootseed right away—a connection much deeper than what he’d felt studying Spanish and German.

Victor Andy, ’20, has been inspired to learn his family’s Yakama language after taking Southern Lushootseed.

He instantly saw relationships between words shared by Southern Lushootseed and his family’s Yakama, links that spoke to the shared experiences of the diverse Native peoples in the Northwest. Some of Southern Lushootseed’s sounds felt familiar and instinctive to his tongue, while others were new and intriguing. Hohn’s classes inspired him to delve deeper into Yakama.

“Because of this class, I come up with my own ideas of how I want to learn,” Andy says. “It provides a basic structure. It showed me aspects of language I’m not sure I would have caught.”

Hohn hopes Southern Lushootseed will become a permanent UW course so it can go on without her. With support from a $1.8 million grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, she’s already created an ongoing independent-study program for her advanced students.

For Hohn, learning and teaching Southern Lushootseed is a journey that’s both intensely personal and bigger than herself. It’s a journey reflected in a handcrafted blanket she was inspired to create, entwined with ribbons bearing the names of her ancestors, her family members and other first-language speakers of Southern Lushootseed.

“I’d love to see as many Native languages as possible at the UW, but this is the language of the land the University sits on,” says Hohn. “Like Chief Sealth said, when the Native people die, we still exist because our spirits are here, our essence is here and our livelihood is still here. We can’t be wiped away.”