For debut novelist, timing of virus is stranger than fiction

Kristen Millares Young (Photo by Jenn Furber)

As a writer, I know all about plot twists. So when the editor wrote to me with a welcome commission—“What’s it like to be a debut novelist in the midst of this crisis?”—I was bemused. She and I know each other from our days at the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, now folded. We had survived socioeconomic cataclysm before. And here we are again, in a pandemic.

The new normal. Connecting with readers is more complicated at a social distance. With a third of my book tour canceled, one third deferred and the last third in limbo, I have been feeling like a fraction of myself. I spent a year organizing 35 panels, performances, signings and teaching engagements to prepare for fraught conversations in person.

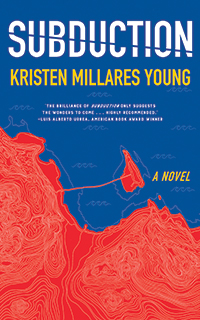

But I know how to create rising action. Know, too, how to chart the fallout of decisions made under duress and in desperate grief. I spent years doing just that while writing my debut novel, “Subduction,” which follows a Latinx anthropologist who violates ethical boundaries and begins an affair while conducting field research on the Makah Indian Reservation in Neah Bay.

Like the trajectories of celestial bodies, our orbits around what we want are recurrent. Published in April, “Subduction” was the very same book I workshopped a decade ago as a grad student at UW, where I arrived as a prize-winning journalist and nonprofit newsroom co-founder who had no idea how to write fiction. I only knew that it moved me. When in need, I reach for novels to remind myself how to live.

How do we reconcile the futures we wished to enact with the paths available to us now? Embracing our own stories is part of the answer. We must not forget what this pandemic teaches us. Our children need us to remember these lessons.

Last winter, I began teaching a class on writing and publishing personal essays through UW Continuum College. As a former Graduate Opportunities & Minority Achievement Scholar, it felt like coming full circle to teach what I had learned as a graduate of the UW Master of Fine Arts program in creative writing. Writing fiction brought me closer to my own story. In my own family’s intergenerational history of bouncing back, I find the forward momentum I need to launch my book. To pivot toward a digital strategy, I will publish short pieces of nonfiction and post “live” readings. I will make this work.

Last winter, I began teaching a class on writing and publishing personal essays through UW Continuum College. As a former Graduate Opportunities & Minority Achievement Scholar, it felt like coming full circle to teach what I had learned as a graduate of the UW Master of Fine Arts program in creative writing. Writing fiction brought me closer to my own story. In my own family’s intergenerational history of bouncing back, I find the forward momentum I need to launch my book. To pivot toward a digital strategy, I will publish short pieces of nonfiction and post “live” readings. I will make this work.

Timing is the master factor—when to begin the story, and when to consider it concluded. For examples of resilience, I have the characters of “Subduction,” who make do with lives they never would have chosen. Through the example of my fiction, which asks hard questions of characters for whom there is no easy redemption, I question the market’s demand for demonstrated transformation. We know damned well that some people don’t change.

But we can be made better in community. UW has become part of what author Ada Calhoun called my “redemption sequence,” in which negative experiences become meaningful through retellings. In my life, I have done my best to craft redemption sequences for difficult eras like the current epoch. Maybe they were already there, but writing helped me see them. Happy to share that The Paris Review selected “Subduction” as a staff pick, I could tell you a success story that rose, clean and shiny, from my UW workshops in Padelford Hall to The Paris Review. But to leave out the downbeats of doubt and the interruptions of rejection would excise the value and drama of that ascent, which made me into the writer I hoped to become by attending UW.

Though striving does not stave off mortality, we can make meaning from times that tore our lives from their arcs. The craft of writing helped me reshape my own narrative and honor my own responsibility to face this country’s uncertain future as a collective. If our ambitions curve toward the common good, we will endure.