Thirty-six elementary school students gave $12 to repair storm-damaged trees in the Washington Park Arboretum. Microsoft Chairman Bill Gates gave $12 million to establish a new Department of Molecular Biotechnology in the School of Medicine and to recruit Professor Leroy Hood from Caltech to head that department.

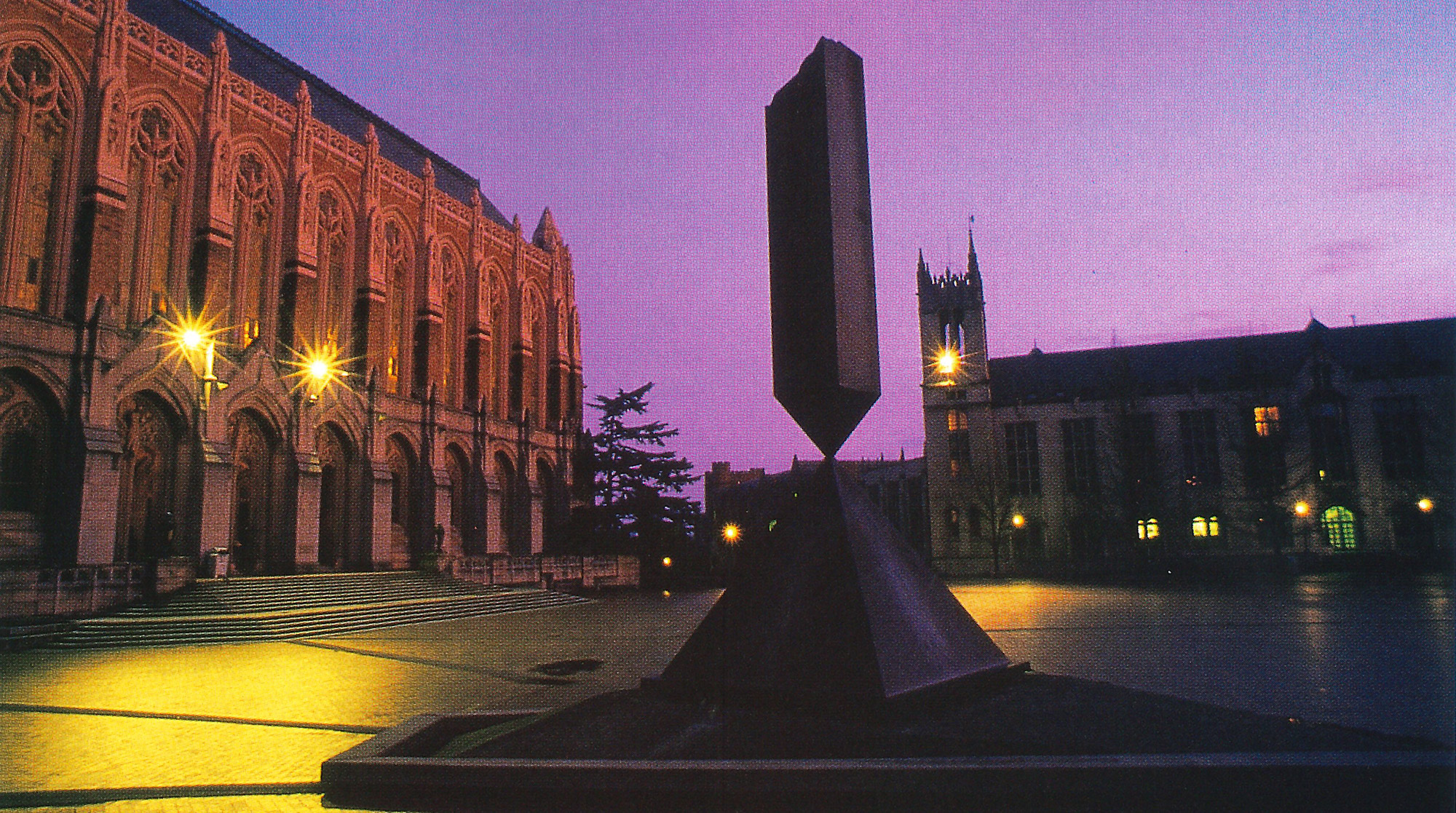

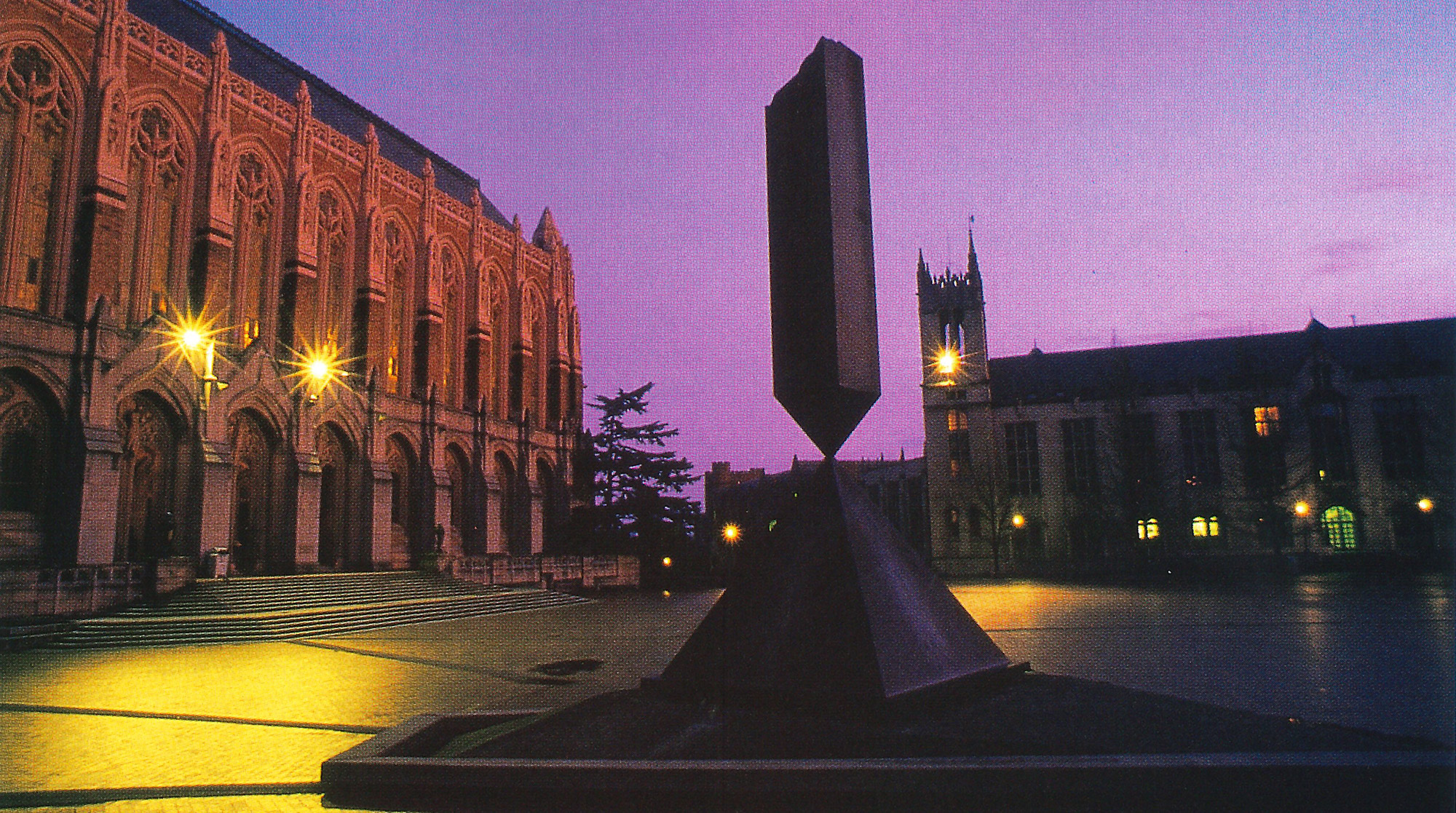

These gifts—the largest and smallest made by individuals to the UW’s first major fund drive, the Campaign for Washington—illustrate the scope of the campaign, from preserving natural resources to laying the foundations for new high-technology research.

The five-year campaign concluded on June 30 with $284 million in gifts and pledges, more than $34 million over its $250-million goal.

“The success of the campaign is a tribute to the University’s alumni and friends who care deeply about this institution,” says President William Gerberding. “It also is a wonderful endorsement of the value of the University’s teaching, research and public service programs. Campaign gifts will make a lasting difference at the University, and we are profoundly grateful to everyone who contributed.”

The University of Washington started with a gift—10 acres of land to establish the “territorial” university in 1861—but for most of its history has not actively sought private support. When Gerberding became president of the UW in 1979, gifts received the previous year totaled just under $7.5 million. In the campaign’s final year, that grew to $59,259,255.

What will happen to the dollars raised during the campaign? Nearly all of them—97 percent—were designated by the donors for a specific program or purpose, like repairing the arboretum’s trees, says Marilyn Dunn, vice president for development. “In most cases, the donors have told us how they want their gifts used—whether for scholarships or library books or laboratory equipment.” Only 3 percent of the dollars received or pledged during the campaign were unrestricted gifts.

The campaign’s highest priority was to increase the University’s endowment. Thanks to campaign gifts and investment returns, the University’s Consolidated Endowment Fund more than doubled during the five-year effort and now totals more than $200 million. Endowments are permanent funds from which income is used for the purpose specified by the donor. The $122.4 million given or pledged for endowments already are having an impact throughout the University:

Prior to the campaign, few people understood the importance of endowment to the University, says Gerberding. “We are delighted that so many people became aware of the University’s need for these permanent funds and responded so generously.”

Other lasting benefits to the UW will come from $42.3 million in campaign gifts for facilities and equipment:

The campaign greatly exceeded its $74-million goal for current program support, raising $119.3 million for a variety of purposes:

The state of Washington added almost $5 million to the University’s Consolidated Endowment Fund during the campaign through programs that match gifts for endowed professorships and graduate fellowships. “These public funds are not included in the campaign totals,” Dunn explains, “but they were enormously helpful in stimulating gifts for our highest priority needs. People occasionally ask whether private gifts replace state money. They don’t. And the fact that the state is willing to match some gifts shows that the legislature not only recognizes the value of private support for the University, but also encourages it.”

Many people and organizations already supporting the University increased their gifts during the campaign. The Boeing Company—at $12.4 million the campaign’s largest donor—is one example. Two-thirds of Boeing’s gift was designated for endowment, including two endowed chairs ($1.5 million each), 10 professorships ($500,000 each), $300,000 for fellowships and $200,000 for other endowments.

“Boeing’s gift is remarkable not only for its size,” says UW Provost Laurel Wilkening, “but also for the amount directed to endowment. The increase in the University’s endowment during the campaign has enabled us to keep many faculty members at a time we might have lost them. We are extraordinarily fortunate that Boeing chose to make such a far-sighted investment in the University’s future, and to extend its giving to new academic areas.”

In the College of Arts and Sciences, Hans Dehmelt was honored by being appointed first holder of the new Boeing Distinguished Professorship in Physics. Dehmelt was one of three physicists awarded the 1989 Nobel Prize in physics.

In the College of Education, Roger Olstad has been appointed the first Boeing Professor of Education. “My hope is to strengthen existing alliances among the University, public schools and the corporate community to improve science education,” says Olstad. “Boeing has been very active in fostering such partnerships, and we’re delighted to have this support.”

Other programs benefiting from Boeing endowments include the School of Social Work, the College of Ocean and Fishery Sciences, and the College of Engineering. Engineering received two endowed chairs and six professorships.

The campaign also inspired many gifts from people who had never given to the University. Several such gifts—including one for $20,000—were received in response to an envelope contained in the final campaign newsletter, which was mailed in May. Jack Sheedy, ’43, had to drop out of the UW after two years and never graduated, but says, “My heart’s always been with the University.” Sheedy sent $1,000 for the President’s Fund for Excellence. “I feel strongly about education and if I can contribute in some way to help create a better education, I’m all for it.”

“Every person who made a gift to the campaign had a uniquely personal reason to give,” says Marilyn Dunn, “and all who gave can feel proud of the difference their contributions are making at the University. But there is one group that deserves special credit for the campaign’s success—the hundreds of volunteers who invested their time and effort, as well as financial resources, in the campaign.”

More than 300 UW alumni and friends in Washington and across the country organized into volunteer committees that helped explain the University’s needs and asked for gifts. “Every committee reached its fundraising goal, and the campaign could not have succeeded without these volunteers,” says Dunn.

“When the Campaign for Washington began, a lot of people thought it was a mountain that couldn’t be climbed,” says John N. Nordstrom, ’59, co-chairman of Nordstrom Inc., who served as volunteer co-chair of the campaign. “I was surprised how many people, leaders in this community, thanked me for taking this on. They thought I was sticking my neck out because there really were no role models for giving to the University on this scale.”

“Many people have given far more than they ever dreamed they would,” adds Donald Petersen, ’46, campaign co-chair and retired chairman and CEO of Ford Motor Company. “Part of what has happened to almost all of them is that they found it has been personally rewarding.

“As a graduate of the University who doesn’t live in the Northwest,” says Petersen, “I have been tremendously impressed at the quality of leadership that exists in the greater Seattle community, and that so many very busy people were willing to put so much personal time into the University. As a result of the campaign, I think people’s aspirations for the University have risen, both within the institution and in the community.”

The University’s successful recruiting of biotechnology expert Leroy Hood to its faculty, with help from Bill Gates, is one example of how those aspirations have changed. Hood’s move with his research team is expected to have a far-reaching impact. Although Hood’s department is based in the School of Medicine, the work he and his research team do is interdisciplinary, bringing together biology, computer science, applied mathematics, engineering, applied physics, chemistry and other disciplines. The group’s invention of sophisticated instruments to study genes, hormones, antibodies and cells was a major contribution to the biological revolution of the 1980s and the burgeoning of biotechnology in medicine and industry.

“The recruitment of Lee Hood will stay in people’s minds as a symbol of the Campaign for Washington,” says Marilyn Dunn, “but that is only one of many good things that are happening here because of the campaign.” Although the campaign’s achievements are most readily expressed in terms of the money raised of the things those dollars accomplish, Dunn says, other important results of the campaign can’t be expressed in dollars. “The campaign brought the University closer to thousands of its alumni and friends,” says Dunn. “That was a very important part of our goal, and we are delighted with the results.”

To help achieve that closer bond, the University’s Office of Development and the UW Alumni Association co-sponsored the UW Beyond Seattle series, programs that brought faculty speakers to alumni gatherings in New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Portland and cities around the state of Washington.

“Working on the Campaign for Washington has been exciting,” says Jon Rider, executive director of the UW Alumni Association. “It’s been great to see so many terrific, talented people devote so much effort to their University. The money given during the campaign is wonderful, but people also want to give of themselves. With that kind of commitment, the University of Washington is going to continue to be the best in the Pacific Northwest and one of the finest in this country.”

The 10 largest gifts:

Total gifts and pledges: $284,001,142