Wired for divorce Wired for divorce Wired for divorce

A UW researcher's study may help predict which couples face divorce, even before they are married.

By Alansa Bates | Illustration by Ken Shafer | Sept. 1992 issue

It's Sunday morning in Seattle. As these newlyweds finish their Starbucks coffee, they settle down on the couch to read the Sunday Times-PI while Bach's Brandenburg Concerto No. 4 plays on a state-of-the-art CD player. It is surprisingly sunny, and they find it hard to concentrate on the news when they can watch boats glide by their windows that overlook the Montlake Cut.

But something’s not quite right in this idyllic scene. Beneath the couple’s casual clothes there are monitors taped to their skin, recording their heart rates.

A different gadget measures their perspiration. That Starbucks they’re sipping will later be collected in a special “potty” in the bathroom, to be analyzed for stress-related hormones. Like an Orwellian nightmare, their every movement, facial expression and conversation is being videotaped by three wall-mounted cameras and watched by observers hidden behind one-way glass. Tomorrow they’ll have to give blood samples for additional analysis.

This is much more than a pleasant waterside apartment. In reality it is a psychology lab, and these newlyweds are subjects in a UW study that may help psychologists such as John Gattman predict a marriage’s chance of survival.

The UW professor, culminating 20 years of research, has married high-tech equipment that measures stress to the latest theories of spousal relationships. His previous physiological research on happy and unhappy marriages has enabled him to predict—with an astounding 95 percent accuracy rate—which marriages will improve and which will deteriorate over the next three years.

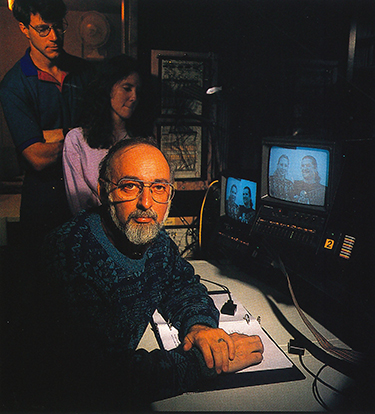

Professor John Gattman sits in his apartment/laboratory as two assistants stand in the background.

“Without the ability to predict divorce, we’ll never understand why marriages fail or work well,” says Gattman, a national expert on marriage and divorce who is frequently interviewed by the New York Times and other news organizations.

Currently, about 50 percent of all U.S. marriages end in divorce, a rate that’s shown dramatic increases in this century. But, Gattman notes, “Past research has been quite unsuccessful at predicting who will separate or divorce.” Out of 1,200 published studies, Gattman found only four that were long-term surveys taken before and after divorce. Most were interested only in the effects of divorce or separation, not in predicting it.

“And none had observed the interaction of couples. So prior research hasn’t even tried to specify which marital interaction processes lead to divorce.”

Gottman’s use of gizmos and Peeping Tom cameras separates him from the norm in couples research. He became interested in biological monitoring because of his 10-year collaboration with Robert Levenson, a Cal-Berkeley psychophysiologist.

Asked why he studies couples in an apartment instead of a lab, he compares his work to a scientist studying bees. “You don’t want to take the bee out of the hive and into the laboratory. You want to look at the bee in the hive.”

It is a large undertaking. Gattman plans to study 50 newlywed couples in his apartment setting, plus test 90 more in his office. His staff includes 20 researchers and 50 undergraduate helpers. Funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, the project is called “Becoming a Family.” Researchers will follow the progress of the couples, most of whom plan to have children, for the first five years after they give birth. “We want to look at the pre-child marriage and see how it changes when a child comes,” he says.

The live-ins typically enter the apartment at 9 a.m. Sunday and stay overnight (No, they’re not monitored after 10 p.m.). The apartment, which has a beautiful view of pleasure-boat traffic on the Montlake Cut, is equipped with a stove, microwave, sink, dining table, home entertainment center (“nicer than mine at home,” Gattman says), two couches—one of which opens to become a double bed—and a bathroom.

The couples bring in whatever food they like and receive no instructions other than to make their interactions as natural as possible. They can make telephone calls, for instance, or work at home if that’s what they usually do.

Among their activities, couples typically read the Sunday paper. Reading habits are more telling than you might imagine. “There are many ways a couple can read the paper,” Gattman says. “For instance, their feet may be touching. Or maybe one will remark about an interesting story—or they’ll discuss something in the paper at length. Or, perhaps, they’ll have absolutely no contact at all over the paper.”

This last scenario may suggest that their lives are already running on parallel but separate tracks, which, the researchers have found, is an early precursor of divorce.

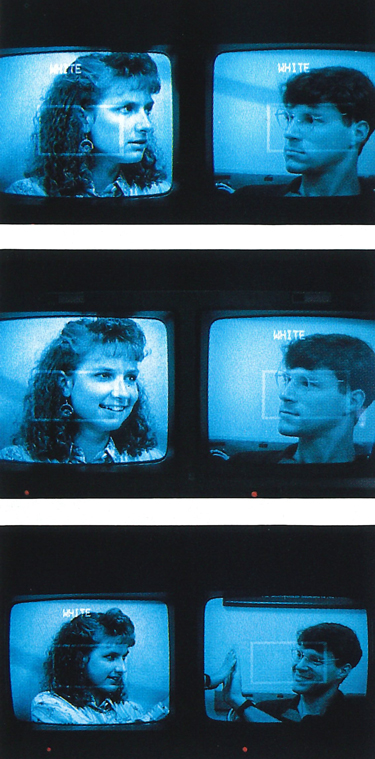

Gattman’s video cameras catch every facial nuance while two research assistants pose as wife and husband.

“The ones who will separate or divorce have already separated or divorced emotionally,” Gattman says. They may have separate interests, friends, likes and dislikes—all areas that Gattman and his colleagues ask about at the end of the weekend, when they have the couples discuss the history of their relationship and status of their marriage.

These discussions can be extremely revealing. One couple in an earlier study had a child and later divorced. In one interview, the wife recalled that her husband, “sort of proposed to me.” She noted also that she “just went off the pill” before she became pregnant, and told her husband about her decision later. And both husband and wife agreed that she often “dragged” him to do things he didn’t want to do.

What is surprising is that emotional separation sometimes occurs in new marriages, although the couples are unaware of it, says Gattman. His current study has already seen one newlywed couple divorce. “Many people are not in love when they get married. Those who do finally separate are already far down the path when we see them in the lab.”

The main sources of couples’ conflicts are: 1. Communication; 2. Money; 3. Sex; and 4. In-laws. The magic recipe for a lasting marriage is, simply, love and respect leading to mutual validation, Gattman says.

The trained observers can spot and track a couple’s marital breakdown by observing their facial expressions and defensive words. Let’s imagine Fred and Linda are reading the Sunday paper. First, there’s typically a complaint, which, of course, occurs in all couples. Linda might say, “It makes me angry when you grab the front page.” By itself, a complaint isn’t necessarily bad, Gattman says, but then can come step two, which is criticism. Linda might add: “You’re the kind of person who would steal my favorite section from me.”

It’s not far from there to step three, an insult. Linda might say: “You’re greedy and self-centered and always thinking about yourself.” This is followed by step four: defensiveness or denial of responsibility by Fred. Finally, step five is withdrawal, also on Fred’s part. Or, of course, the roles could be reversed.

Although most couples evidence some or all of these behaviors at times, many couples are chronically at one stage or another, Gattman notes. If Fred and Linda’s interactions regularly deteriorate to step five, their next stop might be divorce court.

In his research, Gattman has found that facial expressions can predict divorce as a conversation passes along the five steps. He watches for disgust on the wife’s face or fear on the husband’s. Also significant is what the researchers call “miserable smiles,” ones that are “pasted on” and “unreal,” where the corners of the mouth turn up but the eyes remain expressionless.

Another bad omen is “stonewalling” on the part of the husband. This usually follows “hot” marital conflict, which may involve a lot of anger, sadness, whining and complaining by the wife. The husband can become overwhelmed by such emotions and start withdrawing by presenting a “stone wall” to his wife. He tries to keep his face immobile, avoids eye contact, holds his neck rigid, and avoids nodding his head or making the small sounds that would indicate he’s listening.

It may be, Gattman theorizes, that it takes men longer than women to recover from physiological arousal (caused by “hot” marital conflict). Such arousal is more likely to be avoided by men than by women. If the wife tries to reengage her stonewalling husband and fails, she may then withdraw into herself amid expressions of criticism and disgust. As both become defensive, the marriage is often headed toward the rocks.

A sidelight to the husband’s stonewalling, Gattman adds, is that “it predicts his loneliness, which, in turn, predicts the deterioration of his physical health over the next four years. So the stonewaller pays a high price.” On the other hand, “we also discovered that men who did housework were far healthier four years later than those who didn’t,” Gattman says.

Why would couples participate in a study that is so invasive? “They enjoy it,” Gattman says of couples in the newlywed study. In addition, couples are paid $700 to $800 for their participation.

Sometime in the 21st century, when a couple gets pre-marriage counseling, they may face a computer test designed by Gattman. He envisions a program that would allow engaged couples to discover whether they’re destined for successful wedlock. It could warn unlikely prospects, for instance, that their interactions are 75 percent similar to those who later divorce. Then, if the couple still wants to marry, a counselor could refer them to a therapy program “to hopefully move them back into a better stage with better chances,” he says. Those 50 newlywed couples and their Sunday morning idylls could eventually lead to a decline in America’s monstrous divorce rates.