Bill Gates Sr.: An advocate for us all Bill Gates Sr.: An advocate for us all Bill Gates Sr.: An advocate for us all

As a leader in public service and champion of the UW, Bill Gates Sr. leaves a legacy far beyond his legal contributions.

By Hannelore Sudermann | Photos courtesy of the Gates family | December 2020

On the occasion of his 80th birthday 15 years ago, Bill Gates Sr. didn’t receive any traditional gifts. But to his utter delight, alongside an enormous cake, his family served up a better idea that recognized his distinguished career as an attorney: five public-service law scholarships in his name.

The donation to support UW law students every year for the next 80 years might have been the perfect present. It honored Gates’ professional pursuits, his appetite for community service and his belief in the UW as a leader for positive change. The William H. Gates Public Service Law Program—funded with $33.3 million by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation—has been a cornerstone in revolutionizing a new field of law.

Gates threw his considerable energy into helping the students become successful. “He was hands-on in the best way possible,” says Michele Storms, the executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union in Washington. For 10 years, she directed the Gates Public Service Law Program. “He didn’t try to run the program, but he was totally there to be present and engaged.”

When the students delivered formal presentations or had weeknight get-togethers, Gates, whose 6-foot-7 height was hard to miss, showed up at the law school and joined in. “One night we were wrapping up a long week with takeout in a small conference room,” says Colleen Melody, ’04, ’09, one of the first Gates scholars. “He dropped in, folded himself into a chair and took a paper plate of food, just making time to visit with us.” He was interested in how the students were managing law school. Did they have any needs? Could they use any advice?

Gates offered students two key pieces of advice: First, they were there to learn the law. “He said, ‘Don’t be so busy trying to change the world that you don’t get all the foundational material you need to know,’” says Storms. “He wanted them to learn to use the law to [in the words of John Lewis] ‘make good trouble.’” He also told the students to not just think about the work they want to do, but to think about the profession and how to be a leader to make all lawyers better. “That was so important,” adds Storms. “All lawyers should be concerned about how we practice and the connection between ethics and access to justice.”

Even at a young age, it was clear that Bill Gates Sr. was going places.

William Henry Gates II was born into what he once called “a distinctly middle-class family.” He grew up in Bremerton, where his dad owned a furniture store. The UW was his sole choice for college, and just as he was starting classes in 1943, he joined the Army Reserve, knowing he would be called up to serve in World War II his sophomore year. He returned home in 1946 in time to start fall quarter on the GI Bill.

He met his future wife, Mary Maxwell, ’50, at the UW, and they married in 1951. In 1964, Gates co-founded a Seattle law firm that later became Preston, Gates & Ellis (now K&L Gates). Known for his integrity and intellect, he was a force in Seattle’s legal community.

When Gates became president of the Seattle-King County Bar Association in 1970, he had a mission. At the time, Washington had only white judges and hardly any lawyers who were people of color. Gates knew those deficiencies affected the trust clients from minority communities placed in the legal system, as well as the quality of representation they received. He turned to the UW for help, first seeking to increase minority enrollment in the law school. Then he persuaded the bar association’s board to create law-school scholarships for underrepresented students. The bar association now provides $150,000 a year to support underrepresented minority law students at the UW and Seattle University.

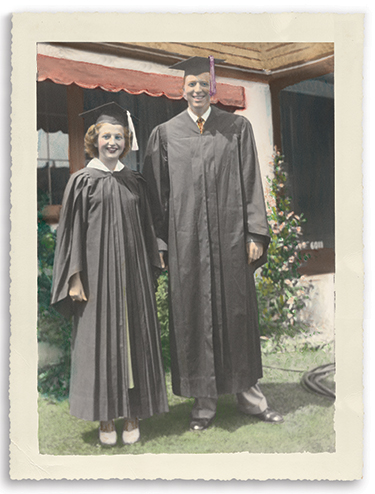

Mary Maxwell Gates and William H. Gates Sr. proudly pose for the camera on their UW graduation day in 1950.

Gates’ volunteer work included serving as president of the Washington State Bar Association as well as the United Way, Planned Parenthood and the Greater Seattle Chamber of Commerce among many other organizations. In the 1990s, he became a co-founder and co-chair of the William H. Gates Foundation, which merged with the Gates Learning Foundation in 2000 to become the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the world’s largest private philanthropic organization.

He also gave thousands of hours to his alma mater, chairing a capital campaign and serving three terms as a UW Regent. For good reason, his family has been described as “The First Family” of the University. Starting in 1975, Mary served three terms on the Board of Regents. Later, their daughter Kristianne Blake, ’75, a Spokane-based business owner and civic activist, served 12 years on the board. Now their youngest, daughter Libby Gates MacPhee, who completed a master’s in social work in 2018, is serving a six-year term. And the entire Gates family, including Bill and Melinda Gates, has given time and tremendous support to the UW. This includes scholarships, endowments and funding to complete capital projects such as Gates Hall, which houses the law school, the Bill and Melinda Gates Center for Computer Science & Engineering and the Hans Rosling Center for Population Health.

Gates and his second wife, Mimi Gardner Gates, visit the Mulendema village in Kafue, Zambia in 2007 on a Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation trip.

When Storms wanted to expand the Gates Scholars program to provide resources to all law students, Gates was a champion. With his support, she increased the number of speakers, mentors and advisers. “I said we need a stronger, broader program. And Bill believed in the vision and seeded $500,000 [in 2010] to get it going,” she says. “It allowed us to bring the public interest programing to a greater swath of students.” The initial grant was followed with another $1 million in 2013.

Today, the Gates program has created a network of talented lawyers in the Northwest and throughout the country. Out of the very first class, Melody has become the founding director of the civil rights division in the state Attorney General’s office. She investigates discrimination and enforces state and federal anti-discrimination laws. She knew she wanted to pursue public service law. Her scholarship convinced her to stay at the UW.

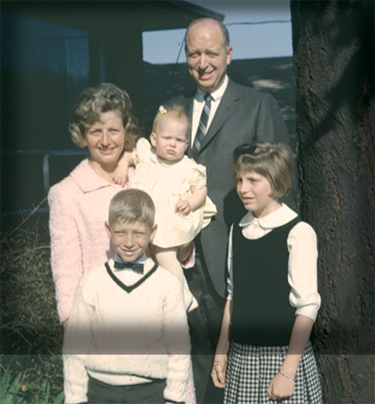

Gates and his first wife, Mary Maxwell Gates, with their three children, Bill, Libby (center) and Kristi (right).

Last year, a fellow scholar, Vanessa Hernandez, ’09, became the director of advocacy for the Northwest Justice Project, the state’s largest publicly funded legal aid program. The Gates scholarship was the very reason Hernandez pursued law. “I knew I wanted to transition from teaching, but I wasn’t interested in going to law school for law school’s sake,” she says. “I wanted to go as part of a community really moving toward social justice and public interest.”

Another from their group, Emily Alvarado, ’09, followed her interest in public service law without having to worry about landing a high-salary job to pay back student loans. Working in housing justice since law school, Alvarado is now the director of the Office of Housing for the City of Seattle. She was also the first law alum to serve on the Gates scholarship board, where she worked alongside Gates in selecting future scholars. “I remember fondly his deep commitment to public service and how gracious he was,” she says. “He really cared about leadership development and about having more young lawyers come up who could be part of the solution.”

Their classmate, Mike Peters, ’09, a two-time Paralympian in soccer, came to law school from a UW faculty position. After completing his law degree, he was awarded an Equal Justice Works fellowship, serving as an immigration attorney for juveniles with the Northwest Immigrant Rights Project. In 2012, he became director of international programs for the City of Seattle’s Office of Intergovernmental Relations. He moved to Germany in 2015 to work for the International Paralympic Committee, where he is now CEO.

During a 2002 visit to Africa, Gates (left), former South African president Nelson Mandela and former President Jimmy Carter hold infants born with HIV.

None of the students had expected the level of personal investment that Gates Sr. supplied. “He was so well-known in the legal community and at the University,” says Melody. “He cared a lot about the program and that we would succeed in public interest law. It was a connection that I don’t think you’d get with anyone else who was as busy and important as he was.”

Alvarado cherished Gates’ vision of building a robust community of lawyers working in public service. “His vision is now a reality,” she says. “Now more than 10 years after finishing law school, I am inspired and challenged by my Gates peers. They are incredible.

“We see Mr. Gates as part of a generation of public service heroes. He worked tirelessly,” she adds. “I feel really honored to be part of a new generation of advocates for social justice that he helped to create. I hope to honor that legacy.”

Pictured at top: Bill Gates Sr. stands with the inaugural recipients of the Gates Public Interest Law Scholarship at their 2009 graduation. From left, their current roles, are Vanessa Hernandez (director of advocacy for the Northwest Justice Project), Michael Peters (CEO of Paralympics International), Emily Alvarado (director of the Office of Housing for the city of Seattle) and Colleen Melody (head of the state Attorney General’s Wing Luke Civil Rights Unit).