UW looks to tuition hikes to avoid deep cuts

Bob Thompson and Bob Edie could be described as typical parents of University of Washington students. They are proud of their children, brag about their accomplishments, and worry about paying for their education.

Thompson boasts of his Husky family, which includes his daughters—Barbara, ’85, and Karen, ’88, who was a Husky cheerleader for two years—and his son, Dean, a senior who is currently president of the Associated Students of the University of Washington (ASUW).

Edie has three reasons to be proud. His two daughters, Emily and Margaret, are planning to be math majors at the UW. Emily is a sophomore, and Margaret is a freshman enrolled under the early entrance program for exceptional students. At the same time his wife, Sue, is working on a master’s degree in drama.

But bring up the subject of the tuition raise currently being debated in the state capitol, and the two parents give an atypical response.

“As a father, I think the UW is a good investment. If it takes a tuition increase for the UW to continue to be an excellent university, I support it,” says Edie.

“I’m divided on this inside,” says Thompson. “After all, I have to pay his bill. But I put a big value on getting a college education. And I really feel this institution is underfunded. The state has an incredible bargain.”

These two fathers know the UW is a bargain, because they work here. In fact, they testify often in Olympia on the merits of tuition reform. Edie is the director of government relations and the UW’s chief lobbyist at the state capitol. Thompson is vice provost for planning and budgeting, basically the UW’s “numbers man,” who has his fingertips on all the financial data.

Thompson’s numbers had looked good until last fall. Over the last six years, the state contributed an additional $50 million to improvements in undergraduate education, minority recruitment, libraries and computing. The state’s investment put faculty salaries closer to their peer average, shrank class sizes, and helped launch construction of new buildings in physics, chemistry and health sciences.

Then the wave of the national recession finally washed over the state. About $900 million in state revenue suddenly went down the drain. Last fall, Gov. Booth Gardner ordered a 2.5 percent, across-the-board cut for all state agencies, which meant the UW had to trim $17 million.

New spaces for 240 full-time students had to go. About $7 million was cut in equipment funds. Approximately 75 employee positions, including non-tenured faculty and staff, were eliminated. And this was after each UW department had to trim 1 percent off their budget at the beginning of the biennium.

More cuts loom on the horizon as lawmakers currently rewrite the state budget. Already the governor has proposed cancelling a 3.9 percent pay raise and trimming almost $150 million from other state agencies, eliminating about 1,100 fulltime jobs. Some legislators are talking about slashing the work force even further.

In this environment, the University could have faced as much as $34 million in extra cuts. Gardner and most legislative leaders do not want to squander the investment they have made in higher education. Rather than impose more cuts, they have turned to tuition reform as the best way to ensure the quality of our community colleges and state universities.

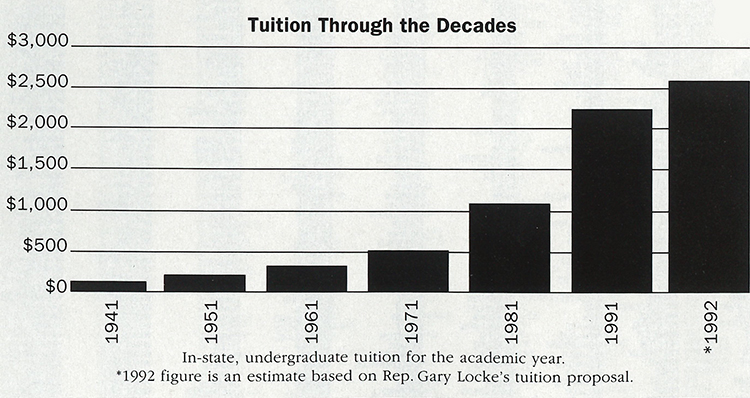

Gardner announced his plan Dec. 16, which would raise tuition to the average of the peer institutions. Tuition would jump at all state institutions. At the UW, resident undergraduate tuition would rise about 24 percent, from the current $2,274 to $2,707 in the fall.

A different tuition plan came Jan. 15 from Rep. Gary Locke (D-Seattle). Also based on peer averages, Locke’s formula gives a break to UW undergrads by holding their increase to $2,620, a 19.2 percent jump. Non-resident undergrads under both plans would face a 28.5 percent hike, paying $8,153 per year.

Students are wary of increases based on peer universities, none more than Thompson’s son, ASUW President Dean Thompson. “Should we raise tuition just because of other universities? That’s an arbitrary and improper way to do it. It breaks the precedent, which is to charge students one-third of the cost of their education.”

The student leader also notes that Washington’s financial aid package is much lower than at many peer institutions. “Michigan has two or three times as much financial aid revenue as Washington,” he says. Instead of raising tuition, he advocates more cuts in other state agencies or some type of tax increase. However, in an election year any tax proposal appears to be dead on arrival.

The debate over increases has caused lawmakers to rethink the entire tuition system. Locke’s bill gives the regents authority to raise rates for non-resident undergrads and all graduate-level students, within a range set by the legislature. Boards could also lower rates for in-state undergraduates. The proposal also puts tuition in a separate account under the ”local control” of each state university.

This is in contrast to the current setup, where the state sets tuition, the UW collects it and then sends it to Olympia’s general fund. There is no clear link between the money sent to Olympia and the funds the state sets aside to run the UW. It would be like taking ticket revenue from Husky football games or Meany Hall performing arts events, and dropping it into the UW’s general operating budget, says Vice Provost Bob Thompson.

“Only five cents of every tuition dollar paid stays on campus. I think most alumni would be stunned by this fact,” says Edie. Washington is one of only four states where tuition is set by legislative statute or regulations. In contrast, 42 states let college governing boards set tuition rates and administer the money.

While Locke’s proposal earmarks the money for each institution, to keep tuition rates under control, he sets a lid based on the cost of education. Currently in-state undergrads pay about 33 percent of the total cost of their education. Locke would raise that amount to cover 39 percent of the cost.

While Locke’s bill does not allow the regents the freedom to set instate undergraduate tuition, any prospect of “local control” terrifies most student leaders, including Dean Thompson. He argues that regents are far less accountable to students than are legislators. He fears that lawmakers might look at the amount of tuition raised locally and automatically subtract that amount from state revenue they had planned to send to campus.

The ASUW leader adds that the regents are “too isolated” from the student body. If, by some chance, the regents gain tuition-setting power, then he would like to see a student appointed to the board. “It would be a recognition of the fact that students are the consumers here,” he says.

These consumers are currently paying lower tuition compared to many other state institutions. The University of Oregon raised tuition 32 percent and Cal-Berkeley raised it 40 percent last fall. “Compared with schools such as the University of Michigan ($4,044) and the University of Virginia ($3,354), the UW is an absolute bargain,” notes the Seattle Weekly.

But what is a bargain to some is a hardship to others. As part of any tuition increase, Edie says, “You’ve got to make sure there is ample financial aid and maybe an increase in the way the state determines financial aid.” A boost to financial aid is one of the few areas where students and administrators are somewhat in agreement. Locke’s proposal includes a companion bill from Rep. Ken Jacobsen (D-Seattle) that would pump an extra $17.4 million into state financial aid coffers. Plus there is the promise to meet all financial aid demand from qualified students in future years.

Unless the tuition system is reformed, the future looks cloudy for the University. UW officials Thompson and Edie see tremendous pressures on the state budget from human services and K-12 education. “What’s going to happen to higher education?” Vice Provost Thompson asks. “There’s going to be pressure to cut down. How are we going to finance this University in the ’90s? We don’t even have the ability to help ourselves.”

Currently, legislators are considering several alternatives. The outcome is uncertain. But Edie is confident some type of tuition reform package will come through with the final state budget. “Tuition is going to go up. It’s not a question of whether, but how much restructuring will be done,” he says. “To pay at least the average of other research universities—I don’t think that is unreasonable.”

Answers to common budget questions

UW officials Bob Edie and Bob Thompson are constantly trying to clear up confusion in the minds of lawmakers, alumni, students and parents regarding the UW budget. Here are answers to three frequently asked questions:

You’re building all those new campus structures. Why can’t you use the money to cover budget cuts instead?

First, says Thompson, it would be illegal. State law prohibits using capital funds for operating budgets. Secondly, money for those buildings comes from bond revenue, and for sound fiscal reasons the state does not finance its operations with bond revenue. (That’s how the federal government built its trillion-dollar deficit.) Thirdly, those buildings are sorely needed. “We can’t attract the best faculty and support modern science and engineering on campus with our current facilities,” warns Thompson. “If you want students to be prepared for the modern world, we have to have modern facilities.”

Your Campaign for Washington has already gone over its $250 million goal with six months to spare. If you have a shortfall, why can’t you take the money from private funds?

“Most gifts the University receives—about 98 percent—are given for a specific purpose or to a specific department,” says Thompson. “Private gifts enhance what the University can do with basic state funding. But gift dollars do not substitute for state dollars, and neither the donors nor the University would ever want them to.”

Can’t you just trim the fat?

This question irritates Thompson the most. “We went through this in 1981-83. The state cut 12 percent out of this place. Since then, hardly a penny of new state money has been added for administrative purposes. The extra revenue has gone to faculty salaries or academic program enhancements. I don’t see that any fat’s been added since 81-83.”