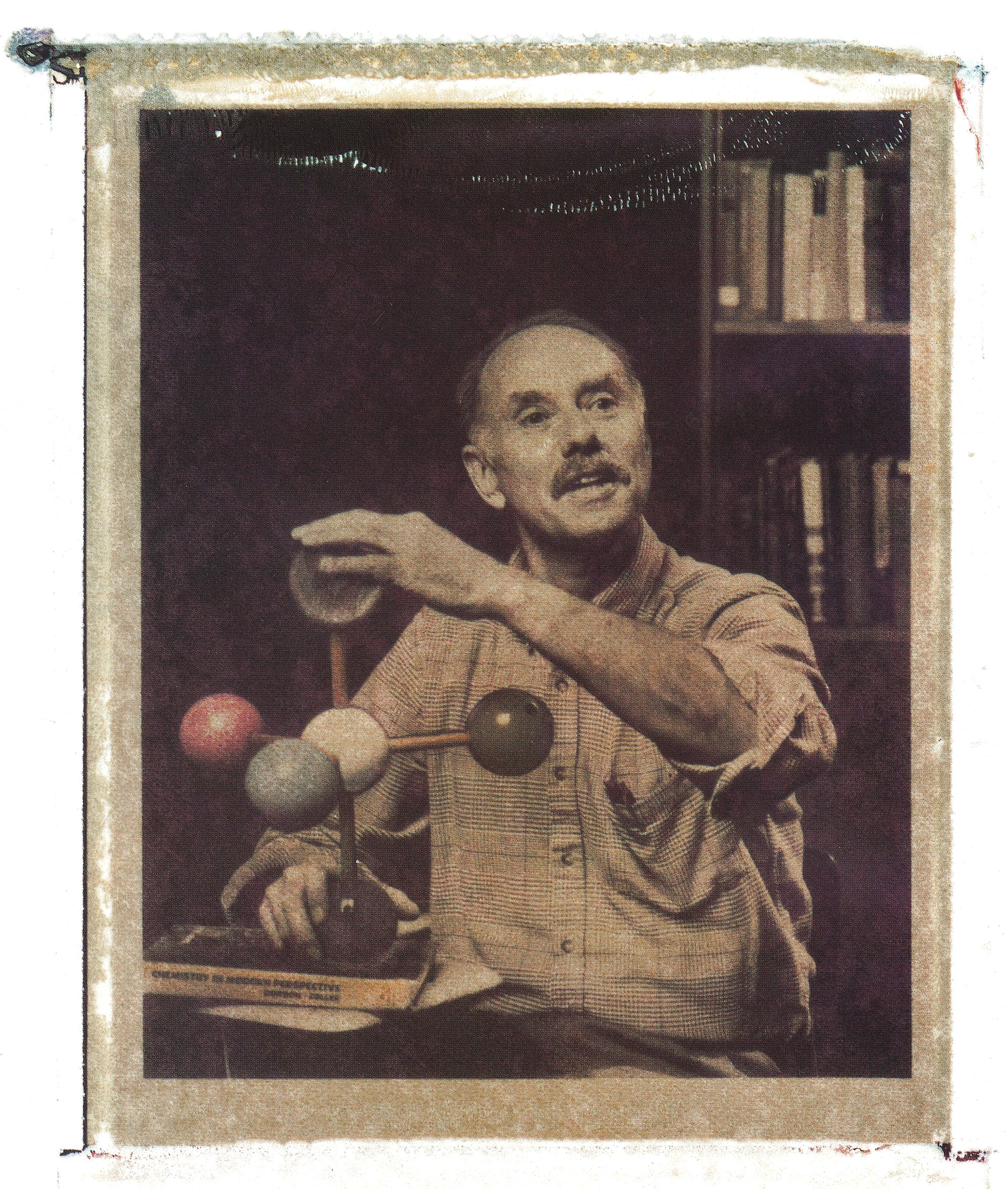

Zoller’s gift Zoller’s gift Zoller’s gift: After brain injury, professor makes new memories

It's not Hollywood fiction, but the true story of a UW professor whose brain injury forced him to start life over.

By Bill Cannon | Photo by Mary Levin | Sept. 1991 issue

Last year, Bill Zoller woke up and remembered his name. It was a small breakthrough. Until that moment, he used to look his name up each morning in a little black book he kept on the nightstand.

The book had many names to choose from. They belonged to his wife, neurologist, preacher, psychiatrist, friends and others he could consult, should he misplace an emotion—or his own identity—during his daily routine as a UW chemistry professor. Now, after three years of practice, he could finally recognize his own first and last name and slip them on like a pair of jeans, one name at a time.

It hadn’t always been like this. Through most of his career, he had worn three names: “Wild Bill Zoller.” Colleagues, amazed at Zoller’s derring-do in the name of environmental chemistry, called him “Wild Bill,” but Zoller can’t remember making that name for himself.

He can’t recall, for instance, ordering a helicopter pilot to deposit him and a portable air sampler into the boiling crater of El Chichon, an erupting Mexican volcano, to assay its contents. Birds, victims of toxic gases, splashed down all around. Zoller was cool. He wore a gas mask. Collecting ended only when acid from the hot puddle he waded through began digesting his rubber boots.

While wooing Zoller from the University of Maryland seven years ago, UW faculty, mindful of Zoller’s wild reputation, speculated on the subject of his literally “mentoring” a grad student to death. You may be unfamiliar with university search committees; they don’t usually grapple with such life-and-death questions.

But the committee made the offer anyway. After a sabbatical year at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, Zoller brought his family, prestige and research grants to Seattle. Soon students rated him among the best in the department. And he should have lived happily ever after.

But he didn’t. Like the main character in the Harrison Ford movie “Regarding Henry,” Zoller’s memory and motor skills vanished in a traumatic brain injury. In January 1987, he left his Woodinville home north of Seattle to drive a visiting scientist to the airport. On the road they came upon an odd tableau: Intersecting headlight beams sprouted like weeds from the ditches. A half-dozen cars had left Highway 520 at a nasty patch of black ice. Wild Bill leaned way over the steering wheel of his Mustang, head pressed against the windshield, to watch for ice.

“Some people would be happy to forget. For example, people tell me I was lucky to have missed eight years of Reagan.”

Bill Zoller

“Apparently, I must not have been all that smart,” Zoller says. “I didn’t know that you couldn’t see black ice.”

The Mustang joined the light show, caroming off two other cars. Zoller’s rib cage supplanted the steering wheel. He was out cold. His companion was OK, but the passenger door was jammed. A pickup truck smacked Zoller’s wreck. The companion then escaped unharmed.

The same could not be said for Zoller. When paramedics pulled him from the car, he wasn’t breathing. Both lungs were collapsed. Forty-five minutes later, doctors at nearby Overlake Hospital began to right Zoller’s insides. His intestines and lungs had swapped places, a contortion allowed by a large hole in his diaphragm. His pelvis and every single rib were broken.

There wasn’t much to be done for Zoller’s brain. He was in a coma. CAT scans revealed two ping-pong-ball-sized hollows behind the temples where blood clots had formed, then dissipated.

It was a good thing that Zoller started out with more brains than 99.9 percent of us. The week after the accident, he came to. His wife, Vivian, was summoned. Zoller looked past her.

“My precious husband was sitting up in bed, expressionless, staring at the television,” Vivian told Nate Carlson, a pre-med student and Husky band tuba player who wrote a term paper on Zoller’s condition. “Despite the shower of kisses, he remained absolutely motionless, void of any emotion. I now know why so many battered women continue to stay with their abusive husbands. At least a beating is an acknowledgment of your existence.”

Vivian’s beating took a different form. Not long after her husband came out of the coma, she brought the family dogs to the hospital. “He knew who they were. He didn’t know who I was.”

After a month in the hospital, the real recovery began. He trained to walk again and to build up his collapsed chest. He had to learn to read again, starting with a second-grade primer and, finally, his own articles. He had to overcome long swings of deep depression.

And he tried to remember.

He remembered hunting and fishing while growing up in Alaska and being the first University of Alaska student accepted into the graduate chemistry program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He remembered his Ph.D. work at MIT, in which he devised an ingenious technique for analyzing air chemistry with unprecedented precision, called neutron activation. He remembered turning down the big bucks from industry and refusing to do “spy science” for a government that waged war in Vietnam. He remembered the early years at Maryland in the late 1960s. He remembered the Beatles and “Eleanor Rigby,” wearing a face that she kept in a jar by the door.

After 1967 or so, the record turned spotty—about half Zoller’s life, and nearly his entire, brilliant scientific career were gone. He forgot about raising a family. His two teenage children were still babies in his mind. Or perhaps he had them mixed up with his two older children, who were already off on their own. To his mind, his wife had aged 20 years overnight.

“Some people would be happy to forget,” Zoller says. “For example, people tell me I was lucky to have missed eight years of Reagan. I don’t know why they say that. Current events—I’m out of it. I don’t know anything about art or politics. I don’t get jokes. I can’t watch television news. I don’t understand the newspapers. The story of Rip Van Winkle is how I explain the confusion to myself.”

“They tell me I made four trips to the South Pole. I don't remember.”

Bill Zoller

But how could he account for the work? What about the 140 scientific papers with his name on them? Or that international symposium program that dedicated its proceedings to Zoller? “Every tropospheric chemistry program in Antarctica is indebted to his initial and continuing efforts to maintain an uncontaminated observatory,” it read.

“They tell me I made four trips to the South Pole,” Zoller says. “I don’t remember.

” … I look at all that guy did,” says Zoller, referring to himself, “and I think, ‘Hey, I don’t know what kind of person he was but he was a pretty good scientist.’ I have to be careful. I’m starting to get a big ego. My wife says that’s good.”

So much in life doesn’t show up on one’s vita. What kind of person was he? Zoller doesn’t have much to go on. He was told he used to like Scotch. The new Zoller says it tastes like medicine and prefers wine. He never used to exercise. Now his days begin with 255 push-ups, 120 sit-ups, 240 knee bends and 30 stokes on a rowing machine. He wasn’t particularly religious. Now he and Vivian are fixtures at the Bothell Foursquare Church.

But there are parts of the pre- and post-accident Zoller that are the same. Zoller’s constant—besides, perhaps, a repulsion to wearing neckties and Vivian’s saint-like support—has been an unextinguishable devotion to teaching. “I figure the reason the Lord kept me alive was to work with students,” Zoller says. Nine months after the accident, he was back in the classroom. He rehearsed as if he were opening a Broadway play.

“My short-term memory is still a wreck. I get very confused sometimes. But I was able to teach just fine.”

After a few quarters, his student rating shot up from average to the high pre-crash levels, in some classes higher. He keeps the yellow forms around for reassurance when self-doubt rises. On nearly every sheet is a comment like “Dr. Zoller does an excellent job explaining the complex in simple terms” or “Dr. Zoller is always prepared, and he repeats the difficult concepts so that I can understand them” or “Dr. Zoller is the best chemistry professor I’ve had.”

Research, in Zoller’s view, is important only insofar as it helps the student. “Research shows how chemistry relates to the world. It gives you real knowledge, the insight you need to teach. You can’t just teach chemistry out of a book.”

Though Zoller’s research has lagged, his ambition to use what his past work has uncovered has culminated in a novel project being copied in several states. It’s what Zoller and his students call the “Science Outreach Program” and others call “Zoller’s gift.”

The program is predicated on a dubious distinction that the environment and public-school science education share: Each is deteriorating. Zoller’s plan was to clean up both by sending UW undergraduates into high schools to talk about greenhouse warming, ozone depletion, hazardous wastes and other problems. In time, Zoller says, high school students will lecture in the junior highs and so on into the elementary schools—a trickle-down theory of science education from the guy who forgot Reaganomics.

Since spring 1990, students have lectured at dozens of Washington high schools, including those in Seattle, Bellevue, Port Angeles, Tacoma, Olympia, Issaquah, Oroville and Snohomish. They have been such a hit that there is a huge waiting list for visits. The program has drawn dozens of students from across campus—from history majors to engineering students—but the money and time for overnight trips to far-flung high schools is tight. So far, funds from the UW and the NASA Space Grant Program have helped cover the costs.

As far as anyone knows, the program is an innovation. In fact, scientists from at least two dozen other universities—from Maryland to Iowa to California—have enlisted Zoller’s help to fashion programs in their states.

“High school students see kids only a few years older discussing these important and complex issues, and they think, ‘Hey, I can do that, too,’ ” Zoller says.

Carlson, the pre-med tuba player who chronicled Zoller, hooked Kentridge High School students when he started his lecture on the ozone hole by asking them to think of the environment as their bedroom. Would they dump waste and pollute the air in their own rooms?

Carlson, whose presentations are every bit as polished as his fingering on “Tequila,” has written a paper on the outreach effort for the Journal of Chemical Education. His biggest kudos came in May as one of a handful of Washingtonians to receive an environmental excellence award from Gov. Booth Gardner.

Carlson, like Zoller, shrugs off the accolades as if he were a top jock on a championship team. “I’d rather not have the focus on me. But as long as the outreach program gets attention . . . ”

Zoller and his students have seen to that. Last spring, he and Albert Shen, one of the three student-founders, spread the word on the program at the national meeting of the American Chemical Society in Atlanta. But their finest hour came when a student in the outreach program, Kevin Gomashchi, turned journalist and wrote an article for the Daily. Gomashchi properly identified Zoller in the story, but a copy editor—no doubt unaware of Zoller’s amnesia—had twice innocently misidentified Zoller as “Fred.” “Professor Fred Zoller is leading a group of adventurous students into the world of environmentalism this summer,” a caption read. “Fred” Zoller also showed up in a pullout quotation: “We did not expect the success we have enjoyed so far.”

For weeks after the article ran, Zoller’s students called their professor “Fred.” Many still call him “Fred.” The ribbing contributed to Zoller’s recovery in an incalculable way. At a Christmas party for participants in the science outreach program, Zoller played along. His name tag read “Hi. My name is Fred Zoller.”

Everyone took that joke as a very good sign.