Was George Santayana correct when he warned, "Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it"?

“History rarely tells us what to do in the future,” says Richard White. “Mostly, what it teaches us is a powerful dose of humility.”

Richard White

White, who earned a master’s and doctorate from the UW, returned last fall to the history department as the first McClelland Professor of History. He joins a growing number of young historians here and elsewhere who challenge the orthodox approach of history—analyzing events of public life.

“History is about telling what events mean. What is meaningful for one generation is not necessarily meaningful for another. Academic history at its worst gives the reader no sense of meaning. The characteristic response to bad history is ‘Who cares?’ Good history answers questions about why this particular set of experiences is important.”

At first glance, his view of history seems to minimize the importance of what historians do. The past, White says, is not a single story with all the facts and influences leading inevitably in one direction; there is no one authoritative account of an historical period. There are subtle nuances, a cacophony of voices, a set of intentions and plans that are partially fulfilled—in effect, a multitude of stories. All contain a portion of the “truth,” but none has a corner on it.

“Historians usually don’t argue over facts; they argue over the selection of facts and their interpretations,” says White. “The most devastating critique of an historian’s work is that it ignores crucial facts that change the story or discredit the interpretation.”

The stories that White tells often are from the 19th century, when American pioneers developed the West. That saga has been told many times, but usually from the point of view of the white male. In those stories the Old West is frequently described as a virgin wilderness, inhabited by uncivilized, disorganized and impoverished bands of Indians.

“The tragedy of American Indian policy is that most of what happened to the Indians that led to dependency was done to them by their friends.”

Richard White

More recently, historians have focused on the exploitation of the Indians at the hands of unscrupulous settlers and politicians, emphasizing the Indians’ growing economic dependence and oppression. Intentionally or unintentionally, the portrait of Indian life arising from these descriptions is scarcely more flattering than that which preceded it. Both interpretations give the Indians little credit for shaping their own fate.

White’s view, however, is more subtle and complex. The Indian communities before the advent of European settlers were dynamic, functional social systems. Tribes had developed different ways of adapting to their environment and altering it as well.

For instance, the Pawnees, who lived primarily in what are now Kansas and Nebraska, built their villages in river valleys, where they lived about half the year and cultivated crops. They introduced new species of corn, beans and squash to the prairie. They also cultivated and preserved wild plants, which they used for medicinal and religious purposes. They set fires in order to maintain the growth of grasses on the Great Plains, providing food for their horses.

Although they did not accumulate a wealth of material possessions in the European tradition, they met the needs of food, clothing and shelter for the members of their group, and they developed strategies for coping with bad weather, failed crops or periodic shortages in game. They had elaborate systems of kinship and authority, as well as systematic religious beliefs that helped guide their actions.

All this may seem obvious. But when White began his research about 20 years ago, the dominant voice through which history spoke was the white man’s.

“The Protest,” a 1904 bronze by Cyrus Dallin.

The break with traditional history came when scholars who went to college in the 1960s entered the professoriate. These individuals lived through an era of social and political ferment and continue to cast a jaundiced eye on the “godlike view” of history, as White puts it, in which historians judge events with Solomon-like wisdom and detachment.

“It’s no accident,” he says, “that no environmental history was written until the last 20 years. The same goes for history written from the point of view of women or minority groups. Historians write about the concerns of their own, contemporary society. History seeks to explain the time in which it is written.”

White says the 1960s influence his research by “giving me a sense of the world as full of great diversity and immense possibility. Even people who perceive themselves as powerless, or who indeed are powerless, can shape their own lives and societies to an astonishing degree.”

During the Sixties, White was a student at the University of California, Santa Cruz. His decision to major in history was almost by chance. “I added up my credits as a senior and realized that the only major for which I’d qualify, given the random nature of my undergraduate career, was history.”

White says few students come to universities with a love of history because so much of what is taught in elementary and secondary schools is of the “Who cares?” variety. One culprit in poor history instruction is textbooks. “The textbook business is very political and the books tend to appeal to the lowest common denominator. A lot of events and facts are covered with little search for meanings, relations and connections,” he declares.

When he finished his B.A., White came to the UW as a part-time student, not yet committed to a graduate degree. He credits UW Professor Vernon Carstensen with being instrumental in his choice of career. “He set exacting standards. Without him, I might’ve never gotten interested in history or finished my degree.” White earned a master’s in 1972, and his Ph.D. in 1975, writing his thesis on the environmental history of Whidbey Island.

Traditional historians warn that one legacy of the ’60s is a “faddish” approach to history. But the possibility of trendiness or changing fashions doesn’t faze White. “We aren’t writing propaganda,” he says. “And the historian’s approach is different from writing fiction. We’re selecting from a larger body of facts. We don’t pretend that we’re saying, ‘This is the way it happened, and only this way.’ More and more, we admit that we’re telling a story that is persuasive and gives meaning to the events. I’m supplying the connection between events, and I’ll match my story against other stories.

“Look at the cowboys. Their heyday was about 30 years. They were in a limited geographic area. They had a fairly minor economic impact. Yet they loom large in the myth of the West and in accounts of the history of the West.”

Richard White

“In this way, history becomes a conversation. It’s never a definitive account of the past. But over time, we have a fuller history. The more you know, the more subtle, interesting history you write.”

White sees no intrinsic reason why other voices and other stories shouldn’t acquire a prominent place in Western history. “Look at the cowboys. Their heyday was about 30 years. They were in a limited geographic area. They had a fairly minor economic impact. Yet they loom large in the myth of the West and in accounts of the history of the West. But the West was full of a variety of people.”

White’s account of the West focuses on the changes that took place in various Indian nations over time, with particular emphasis on the role of the environment.

White tells the story of tribes that had been self-sufficient for centuries. He writes about how they manipulated their environment—through farming, harvesting, hunting and burning—to meet their needs for food, clothing and shelter. He is skeptical about claims that the West was “pristine ” or “natural ” before European settlers came. What he finds in the West, as far back as there were inhabitants, is a series of “human-influenced landscapes.”

As the environment changed, the Indians’ economic, social and political culture changed. As the buffalo was hunted to the point of extinction, as competing tribes grew bolder, as populations were devastated by European diseases, a way of life was lost. The facts of Indian history are reasonably clear: Indian nations that for centuries had been self-sufficient were, by the early 20th century, more dependent upon the federal government than any other group in the country.

The “why ” of this history is more complex than some people would choose to make it, White says.

“The real tragedy of American Indian policy is that most of what happened to the Indians that led to dependency was done to them by their friends. The policies … usually were adopted in the name of preserving the Indians. To save them, the government sought to change their way of life. The situation is complicated—there certainly was plenty of hate among some pioneers—but overall, the policies were not driven by malice.”

White’s work is filled with lessons about the unintended consequences of man’s actions. Europeans, for example, sought to make peace between the Choctaws, who lived in what is now Mississippi, and neighboring tribes. One consequence of peace, however, was the elimination of a “buffer ” zone between the tribes. That uninhabited zone had been a natural breeding ground for replenishment of game.

With peace came increased hunting in the zone, greater absorption of Indians into the market economy, and a gradual loss of game that, along with other factors, caused a major change in the tribe’s food and diet. This, in tum, had additional consequences for the environment and for the Choctaws’ traditional way of life.

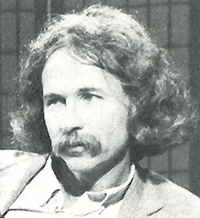

“The Cowboy” by Frederic Remington is reproduced courtesy of the Amon Carter Museum. The 1902 painting was on view during “The Myth of the West” exhibit recently mounted at the UW Henry Art Gallery.

A careful study of Western history makes White suspicious of any conspiracy regarding the fate of the Indians. “At best, people achieve only a portion of their ends. At a certain point, events themselves seem to take over. It’s what makes history so complicated and fascinating. It’s hard to draw lessons. All the facts aren’t under control. No plans are perfect. History is shaped by people’s intentions but is not made predictable by man’s choices or by technology.”

White finds that most of the responses he receives from Indians regarding his research are positive.

“It’s actually more enthusiastic than I’d have expected. My work portrays Indians as more than just victims. But because their stance as victim can be politically useful, some object to finding their position undercut.”

If history is any guide to how relations with Indians should proceed now, it tells us that greater empowerment of Indians could lead to a more self-sustaining Indian economy, says White. “One of their great assets in the West is control of water. If they maintain control, if their rights aren’t compromised when they become inconvenient for whites, they could begin to rebuild. … The worst thing that whites could do is to redesign the world, to eliminate the rights granted by treaties.”

The UW alumnus presents his ideas in a provocative course on the subject, “Inventing Indians,” which deals with both environmental and Indian history. In addition he teaches American and Pacific Northwest history and leads seminars on environmental and Indian history.

In the classroom, White’s approach to history can be jarring. “For many students, it’s disconcerting to learn that you can’t write an authoritative account. For graduate students, it may the first time in their education as historians that they are asked to be self-reflective, to examine what they do and how they do it.

“One of my assignments for undergraduates is to ask them to write about their family, to attempt to interpret events that have occurred in an historical context. Many of them learn for the first time about the difficulties in writing history. They become suspicious of what family members tell them. They become better judges of the reliability of different sources of information. What they end up doing is telling a new story, different from what their parents told them.

“They also become better readers of history—they’re more suspicious, critical, more willing to argue and analyze—which should be the goal of a good education.”

White’s reputation as an excellent teacher follows him from previous institutions. He won teaching awards at both Michigan State University and at the University of Utah. Winner of Guggenheim and Rockefeller fellowships, in 1990 he was named the first holder of the John and Burdette McClelland Professorship in Pacific Northwest History, a professorship established with funds from the McClelland family.

John McClelland Jr. is founding editor of the Washington State Historical Society Journal, Columbia, and was president of the society from 1982 to 1988. His lifelong interest in this region’s history includes the publication of several books, most recently Wobbly War: The Centralia Story. Beyond the creation of the professorship, the gift from the McClelland family also helped to create a Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest within the Department of History.

Part of the McClelland Fellowship will help White with his research and writing. His most recent books are History of the American West: It’s Your Misfortune and None of My Own, and Middle Ground: Indians, Empires and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650-1912.

Perhaps because he’s writing about the West, White ascribes an absolutely essential role to myth. According to White, myth is not the opposite of truth. “It is an alternative way of understanding the past. At many points, it overlaps history; it contains actual events. There is no fixed place where ‘real’ history stops and myth begins. Figure after figure is acting out a life in both a real and mythical world.”

When he talks about myth, White is fond of telling a story about Kit Carson. The legendary frontiersman, while attempting to rescue a woman from Indians, chances upon a dime novel in which he, Carson, is the hero. The rescue attempt is unsuccessful, but Carson becomes fascinated by the fictional Carson, the vaunted rescuer of thousands of helpless citizens and the slayer of hundreds of Indians. He laments his failure to live up to the standards of his fictional self. Carson eventually writes a book of his own exploits, based on the dime novels as well as on what he actually did.

“Since the beginning,” White says, “fact and fiction about the West have been intertwined. The process is ongoing. The West has always been a place to conduct a mundane life on an epic scale. It is the most strongly imagined section of the United States.”

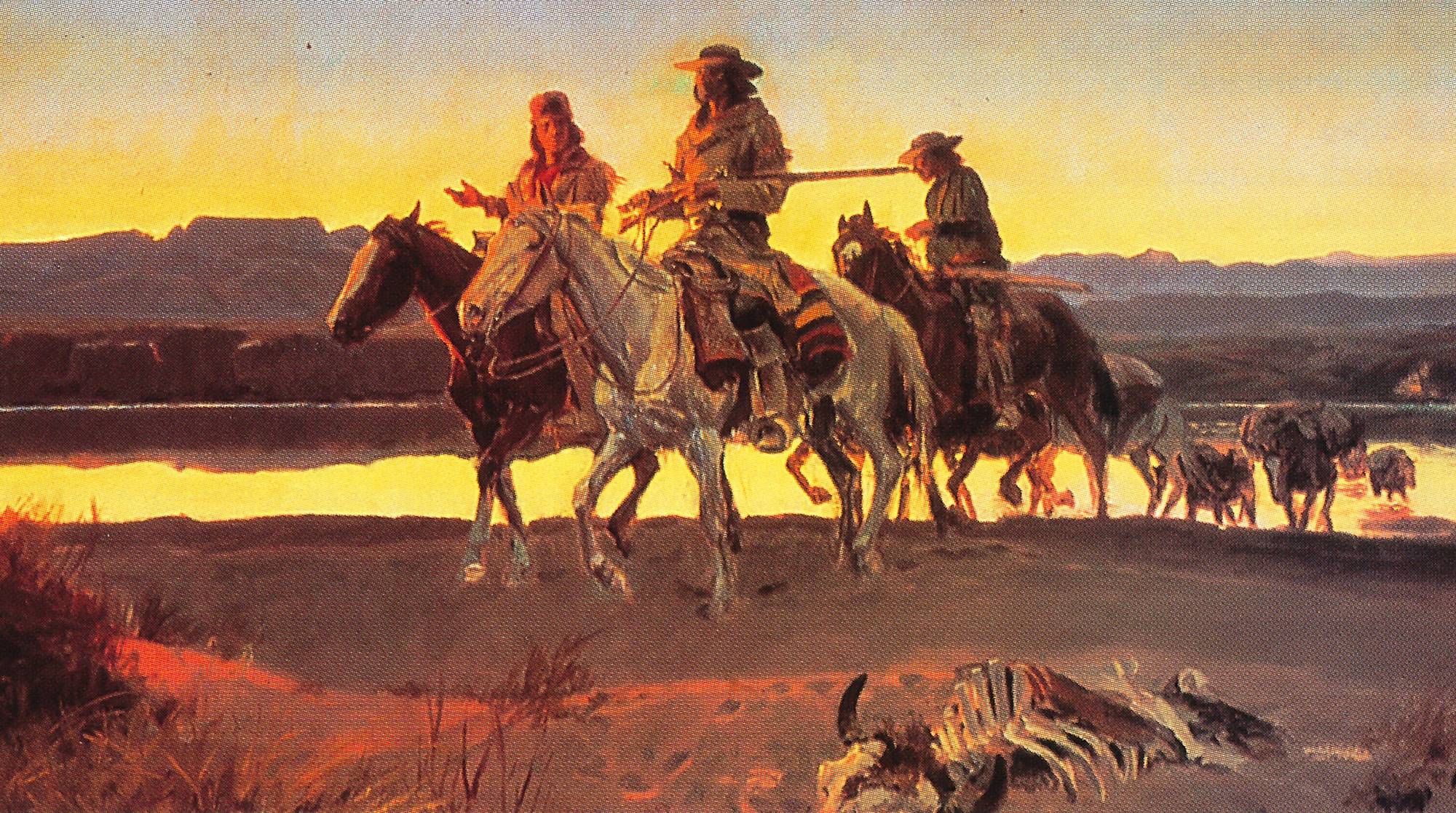

Pictured at top: “Carson’s Men” by Charles M Russell is reproduced courtesy of the Gilcrease Institute of Amfrican History and Art. The 1913 painting was on view during “The Myth of the West” exhibit recently mounted at the UW Henry Art Gallery.