Pulitzer winner Timothy Egan, ’80, writes of KKK’s rise and fall in the North

Timothy Egan

Timothy Egan didn’t set out to write about one of the darkest episodes in American history. The former New York Times Northwest correspondent—a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter—is one of the country’s leading voices of the West. And he wasn’t planning on finding his next gripping tale in America’s heartland.

But his exploration of the history of the Ku Klux Klan in Oregon, which had a Klan-backed governor a century ago, led him there. As Egan, ’80, started digging into Klan history, he found his way to Indiana of the 1920s. “Holy cow,” he says. “Here is a state where one in three white males swore allegiance to white supremacy.” The pervasive influence reached to Ku Klux Kiddies and women’s brigades, and “at the root of it all was a con man, a classic American con man,” Egan says.

Egan’s latest book, “A Fever in the Heartland: The Ku Klux Klan’s Plot to Take Over America, and the Woman Who Stopped Them,” was released in April. It centers on the rise and undoing of D.C. Stephenson, a grand dragon of the KKK, and the rape and murder of an adventurous young woman named Madge Oberholtzer, who, as she was dying, described the kidnapping and rape that would lead to Stephenson’s arrest and trial. “It’s a fabulous story. A monster takes over the state,” says Egan. “It turns out he’s a psychopath.”

Stephenson, who had tried to rise to power through local politics and discovered he could wield more influence through the KKK, united as many as 250,000 Indianans around issues of morality and racial superiority. Working with Protestants, policemen and politicians—all the way up to the Indiana governor—he grew his influence—and KKK membership—in Indiana and beyond, setting his sights on becoming the president of the United States. Oberholtzer’s deathbed testimony exposed his depravity and led to his trial and conviction. While the story played out on the front pages of the nation’s newspapers, it has largely faded into history. The artifacts of the massive movement—the hoods, robes and membership cards—had been tucked away into attics and basements or destroyed.

Egan’s journey to finding and telling compelling stories started at home in Spokane when he was growing up. One of seven children in an Irish household steeped in storytelling tradition, “you tried to hold attention at the table for a few minutes,” he says.

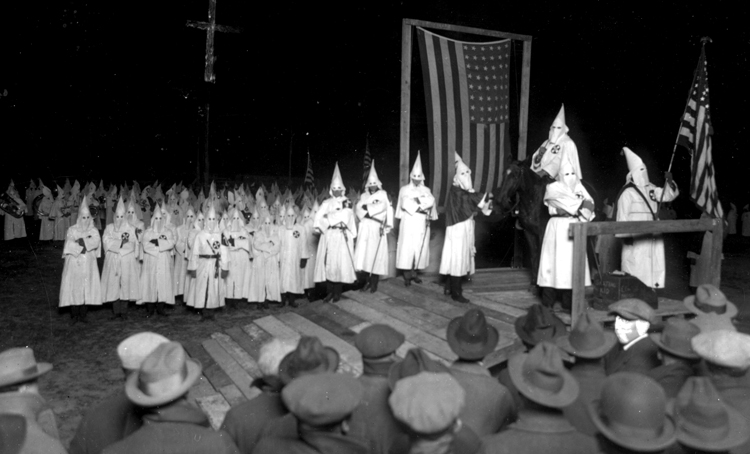

In 1922, more than 2,000 people attended a Klan initiation in Marion, Indiana.

His mother’s love of history and literature primed him for his college explorations. “The real break for me was the UW,” Egan says. He credits his love of rich stories to Professor Willis Konick, who taught wildly popular comparative literature classes with a particular focus on Russian literature. Books, like Fyodor Dostoevsky’s “The Idiot,” were originally published serially in newspapers and magazines, offering Egan a framework for crafting detailed, feelings-driven prose, and doing it at newspaper length.

He also wrote for The Daily, where he was surrounded by talented classmates. Three other Pulitzer Prize winners came out of Egan’s group: writer Peter Rinearson, writer Evelyn Iritani and editorial cartoonist David Horsey. “We learned so much from each other,” Egan says. “We got to do anything and everything. We encouraged each other and competed with each other.”

In 1989, he was hired by The New York Times to report stories from the Northwest. The job caused Egan, a third-generation Northwesterner, to look at the region through different eyes since he was now describing the West for the rest of the country. “My editors really didn’t know anything about the Northwest or Alaska. It was a tabula rasa, and I could paint on that anything I wanted,” he says. “That was a huge responsibility.”

He wrote about river dams, cattle grazing, Alaska oil spills, Indian sovereignty, spotted owls, Montana trout, wolves, salmon, school shootings and politics. In 2001, he was among a team of reporters to win the Pulitzer Prize for a series in The New York Times: “How Race is Lived in America.” His contribution featured Gov. Gary Locke and Ron Sims, King County executive.

He wrote about river dams, cattle grazing, Alaska oil spills, Indian sovereignty, spotted owls, Montana trout, wolves, salmon, school shootings and politics. In 2001, he was among a team of reporters to win the Pulitzer Prize for a series in The New York Times: “How Race is Lived in America.” His contribution featured Gov. Gary Locke and Ron Sims, King County executive.

Around the time he started reporting for a national audience, Egan published his first book, “The Good Rain,” an exploration of the terrain of the Northwest, of its history, politics and landscape. He followed that with the true crime mystery “Breaking Blue,” which took him back to his hometown of Spokane to tell the tale of a 1930s murder and police conspiracy that lay hidden until 1989. “‘Breaking Blue’ was just a really good story,” Egan says. “And it was a chance to recreate the 1930s.”

He visited the ’30s again in “The Worst Hard Time,” an accounting of the survivors of the Dust Bowl. “I interviewed so many people who had so many of these great stories, but I had to leave a lot of it on the cutting-room floor,” he says. The book won the Washington State Book Award in History and the 2006 National Book Award for Nonfiction.

Egan particularly enjoys delving into history and traveling back in time to bring readers along on a journey. The latest book let him do just that: “During the pandemic, I traveled to a place 100 years ago,” he says. He visited Indiana in person to explore the communities in the book. “I go to places to know what the air is like, what the weather is like, what the food is like,” he says. “I go to see the flora and the fauna, the things that give flesh to the story.”

“A Fever in the Heartland” is Egan’s ninth book, and in the weeks around its release, reviewers were drawing parallels between that episode and recent events. In his blurb for the book jacket, author Erik Larson called it “Compelling and chillingly resonant with our own time.”

For his part, Egan didn’t go into the project seeking parallels. He wanted to rattle the notion that the Klan was solely in the Deep South. “It was never more ascendant and powerful than when it took hold in the North,” he says. “I think we’re stronger as a nation for knowing this history and seeing how we overcame it.”