Investigating a medical mystery Investigating a medical mystery Investigating a medical mystery

Driven by experiences, a UW doctor leads a research center investigating the link between transplants and cancer.

By David Volk | Photos by Rick Dahms | December 2023

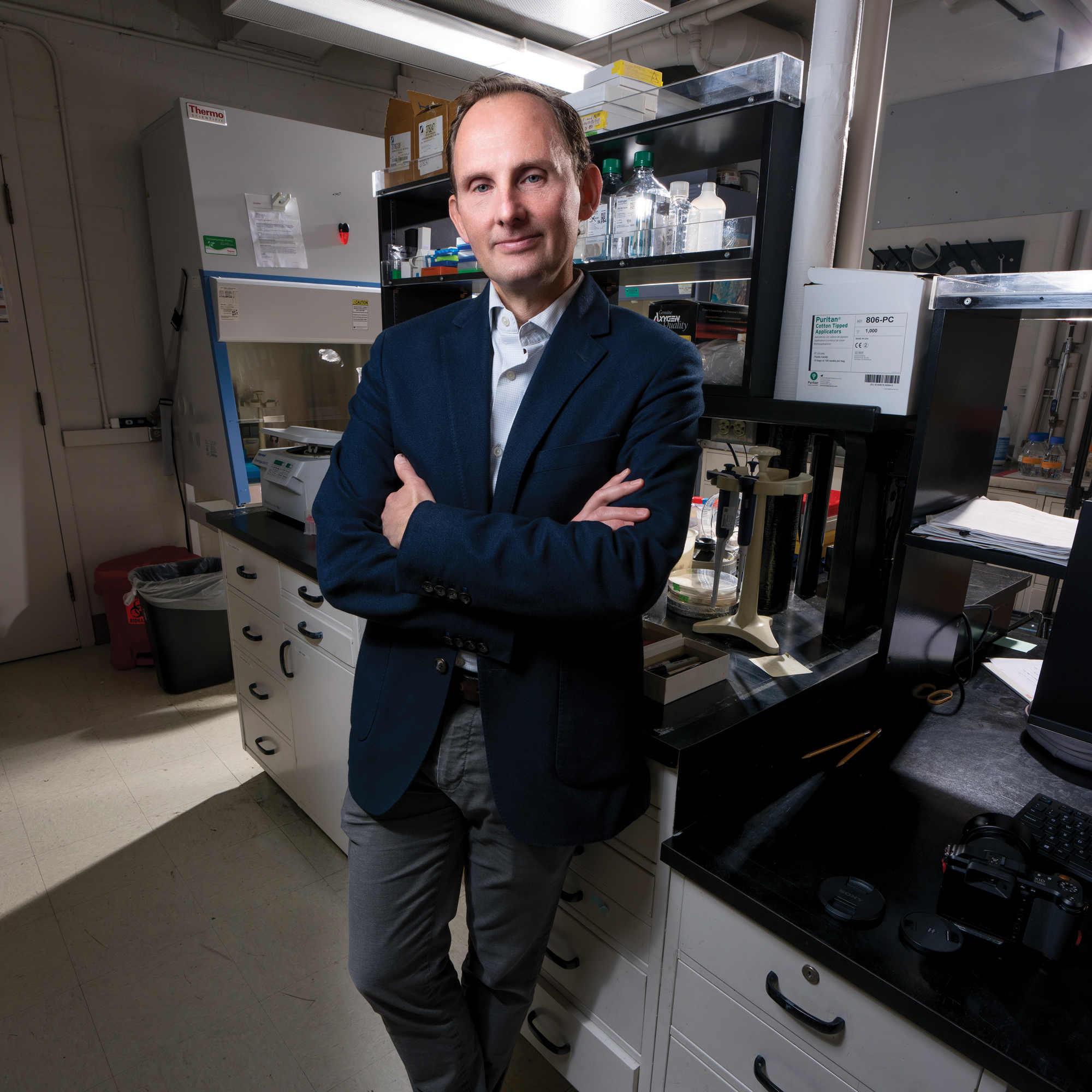

Dr. Chris Blosser, a nephrologist at UW Medicine, began to realize his dream of accelerating research for solid organ transplant and cancer treatment and for providing coordinated care to such patients with complex medical needs three years ago when he established the Center for Innovations in Cancer & Transplant [CICT] at the University of Washington and the Cancer and Organ Transplant Clinic [COTC] at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center. Part of the inspiration for the center arose after the deaths of his mother and his aunt.

Blosser says both women died by the age of 50 because of complications following kidney transplants. Both suffered from polycystic kidney disease (PKD), a genetic kidney disease that forced them to live on dialysis and then receive transplants when their kidneys failed. Both women died not long after they had what should have been life-extending procedures. His mother died of a severe infection, and his aunt fell victim to lymphoma just six months after her transplant.

Looking back on it now, the way his mother lived her life may have had an even bigger impact. Although she was not aware of the cause at the time, she almost died when she gave birth to her son because of her kidney disease. Once she recovered, however, she went back to teaching nursing, working as a nurse in a hospital and caring for her family.

“That was enough of a model to say I actually think I could be someone who could help people’s lives be better. And as I looked around, being a doctor and a scientist at the same time are things that I could do to help,” he says.

“The work that I do is personal in that I’m driven by my personal experience. It’s also personal in that every single person I meet helps me be a better person.”

Dr. Chris Blosser

It wasn’t long before Blosser noticed that more of his patients developed cancer after they received transplants—the same way his aunt did. “Finally, a couple of my patients who I felt close with were diagnosed with metastatic cancer not long after their transplants, and I couldn’t help them live as well as I had hoped,” he recalls. Blosser soon came to realize that cancer had become the second-leading cause of death among kidney transplant patients. Recipients who were older or suffered from chronic conditions were more likely to develop cancer, and he was frustrated that no one was doing anything about it.

“It was the kind of thing where there were a couple of people that were talking about it, but no one was giving an effort to study the problem,” he says, adding, “So I went ahead and wrote a grant that got funded.”

A different vision

To understand how CICT works, it helps to understand the path that many cancer survivors and transplant patients travel. To outsiders, remission and transplantation appear to be a Hollywood ending where patients can move on to a carefree life. The truth is more nuanced, including lifestyle changes, daily medication and fear of recurrence.

“I saw an unmet need for patients because as people are aging and living longer, we’re seeing more people develop cancers and then need organ transplants, while people who receive organ transplants are two to four times higher risk for cancer after that,” Blosser explains in a video on the CICT website.

“Organ transplant recipients require lifelong immunosuppression to prevent transplant rejection. All the while, oncology has developed therapies that turn on the immune system to successfully attack the cancer. If you have both an organ transplant and cancer, the optimal therapies work against each other,” he explains in the presentation. “This can result in poor outcomes and serious side effects, including transplant rejection.”

The medical system’s practice of “silo-ing” treatments further complicates the issue. Often, patients have to visit a transplant specialist and then a cancer specialist, and there’s no effort to coordinate care. Blosser saw the problem frequently when patients would visit a cancer clinic and “once in a while, I would hear from that cancer doctor, but usually not. And it became increasingly clear both in my experience and those [of] patients who were telling me they were frustrated by trying to manage this on their own where there was not enough communication [and] clear support for them across that separation between cancer clinic and transplant clinic care. It became obvious that I needed to create something to bridge that gap.”

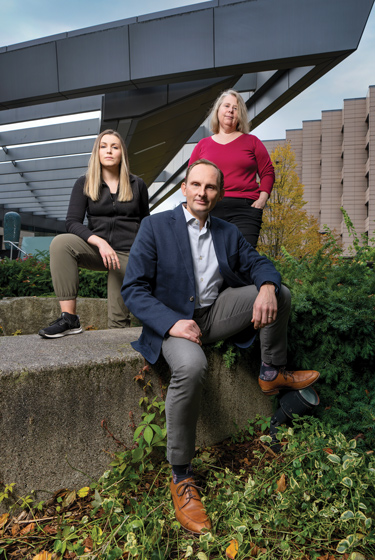

Members of the UW’s Center for Innovations in Cancer & Treatment team are research coordinator Caitlin Gard, left, director Chris Blosser and research manager Barbara Kavanaugh.

The Cancer and Organ Transplant Clinic, which opened in September 2021, is the result. This clinic’s approach helps assure coordination of care, because it relies on the expertise of both oncologists who specialize in 12 of the most common types of cancer and transplant doctors who focus on kidney, liver, lung and heart transplants. The way the clinic handles treatment also helps.

A patient sees both specialists independently during the same clinic encounter. Then the transplant doctor and cancer specialist discuss treatment options and return together to discuss recommendations with the patient and caregiver on how to manage the condition. The care team also records the meeting and puts the audio recording on a flash drive so the patient can listen to it later. “Many times, patients are so stressed by the process that they don’t remember all of the details, and it gives them a chance to go back and listen to it again. If they have questions, they can follow up with us,” Blosser says.

Coordination between caregivers is especially crucial, given the contradiction between immunotherapies and immunosuppression of individual patients as well. Paris Malachias is a good example.

After a sudden case of kidney failure forced the New Orleans resident to get a transplant 18 years ago, he remained healthy with the help of anti-rejection medication until a pimple popped upon his face in September 2022. When the blemish wouldn’t go away, a dermatologist performed a biopsy and discovered it was Merkel cell carcinoma, a skin cancer that is considered among the most dangerous because it’s one of the most likely to spread to other parts of the body. When discovered early, it can be treated. But the cancer is so unusual that not everyone knows how to treat it.

“It’s super, super rare. There’s about 1,300 cases a year, but very few specialists in the country for it. We didn’t trust the hospitals there [in New Orleans] because they have very little experience. The doctor said it was his very first case,” says Malachias’ daughter Anna.

The family had heard of the Seattle clinic, but once they realized that one of the world’s top Merkel cell cancer experts, Dr. Paul Nghiem, was on staff at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, they moved to Seattle so the elder Malachias could be treated there. That doesn’t mean the 74-year-old wasn’t worried about the outcome, though.

“I was worried about my health, and I worried if I could lose my kidney, because before I had a transplant, I had one month of dialysis. It was very hard, and I never wanted to go back on dialysis,” the elder Malachias says.

Blosser initially treated him with the immunotherapy Pembrolizumab and performed DNA tests to monitor kidney function for indicators of potential rejection. When he noticed those signs, he says, “We temporarily increased his immunosuppression … and backed off enough that he is now four months into the treatment and showing great response to his cancer. His kidney transplant is doing great, and he’s showing great response to the immunotherapy. Right now, we’re really hopeful that he’s going to achieve a cure.”

Four months in, Malachias says he is doing much better than he initially expected. Both he and his daughter understood that there was a high risk of losing his kidney in the first few months, and were then pleased to see that the first and second treatment substantially lowered the level of cancer. Although he still had a few more treatments to go, Malachias says, “They saved my life, they saved my kidney.”

Living longer with transplants

Malachias and his family are hardly alone. A 2020 report of the U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients indicated that more than 42,000 transplants are performed in the U.S. every year and that 430,000 people are living with such transplants. The more successful the transplants are and the longer they last, the greater the risk recipients have of contracting cancer.

And the cancer patients of the future won’t just be older adults, Blosser says. “The growth in the number of younger recipients who are likely to live longer means the chance of an increase in the number of younger cancer patients. That’s where the research arm comes in. Blossser says the center’s goal is to focus on three key areas—population trends, patient outcomes and clinical research. Population trends are important because they help determine what significant risks people might have for cancer, their likelihood of remission with certain treatments and even whether certain types of patients are at greater risk for certain types of cancer. Reviewing patient-reported outcomes through surveys they fill out themselves also provides insight into what role social factors like racism, education level, insurance and environment play in recovery when someone develops cancer.

Clinical translational research is also important because it allows the CICT to take basic research about the immune system and combine it with discoveries made within CICT itself to improve treatment. At present, most of the focus is on lymphoma and kidney cancer because they are the biggest killers of transplant patients, Blosser points out.

Creating a patient registry is equally significant. Having what Blosser sees as the only registry that has patient data from cancer centers and programs across the country allows CICT to collect vital data it can use later. As an example, he says the center would be able to look at outcomes for similar patients under similar conditions to determine which approaches appear to work best. In addition, it could help identify ideal candidates for a variety of research projects.

Blosser says he hopes the program will grow from just collecting data to obtaining blood and tissue samples from every patient. “Having the tissue or the blood would then give us the chance to dive even deeper into what it is about that person’s cancer, for instance, at the biological level that allows them to respond better than someone who doesn’t respond.” That goal will have to wait until the CICT has the funding and the space, however.

Tami Sadusky, who has undergone three organ transplants, is a former longtime UW employee and a member of the Center for Innovations in Cancer & Transplant Community Engagement Committee.

Blosser has a fundraiser page on the Fred Hutch Cancer Center site through which he hopes to raise $50,000. Tami Sadusky, a recipient of three organ transplants and the founder of the Endowed Fund for Diabetes, Kidney and Transplant Research at the UW, is a big supporter of the CICT’s work and the clinic’s approach. “I think it will make a huge difference,” she says.

When Blosser isn’t treating patients or working on grants to secure additional funding, he is focused on recruiting more patients and organizations to join the registry to improve its diversity and accuracy. “It’s relatively easy to study people who have money and come to the Hutch. It’s much more difficult to do well-done research for people who have limited means, who are underrepresented or are marginalized. Those patients are at higher risk for these conditions that we are talking about,” he says.

“The work that I do is personal in that I’m driven by my personal experience. It’s also personal in that every single person I meet helps me be a better person,” whether that’s a patient he treats at the clinic or the young transplant patients he sees at Seattle Children’s, patients he knows he will see years down the road at the COTC.

“I want to raise awareness that this is not something that is an old-person problem. It’s a risk for all of our transplant patients, even young adults who develop cancer because they got their first transplant when they were 3 years old or 10 or 16.”