City Hall's top dawg City Hall's top dawg City Hall's top dawg

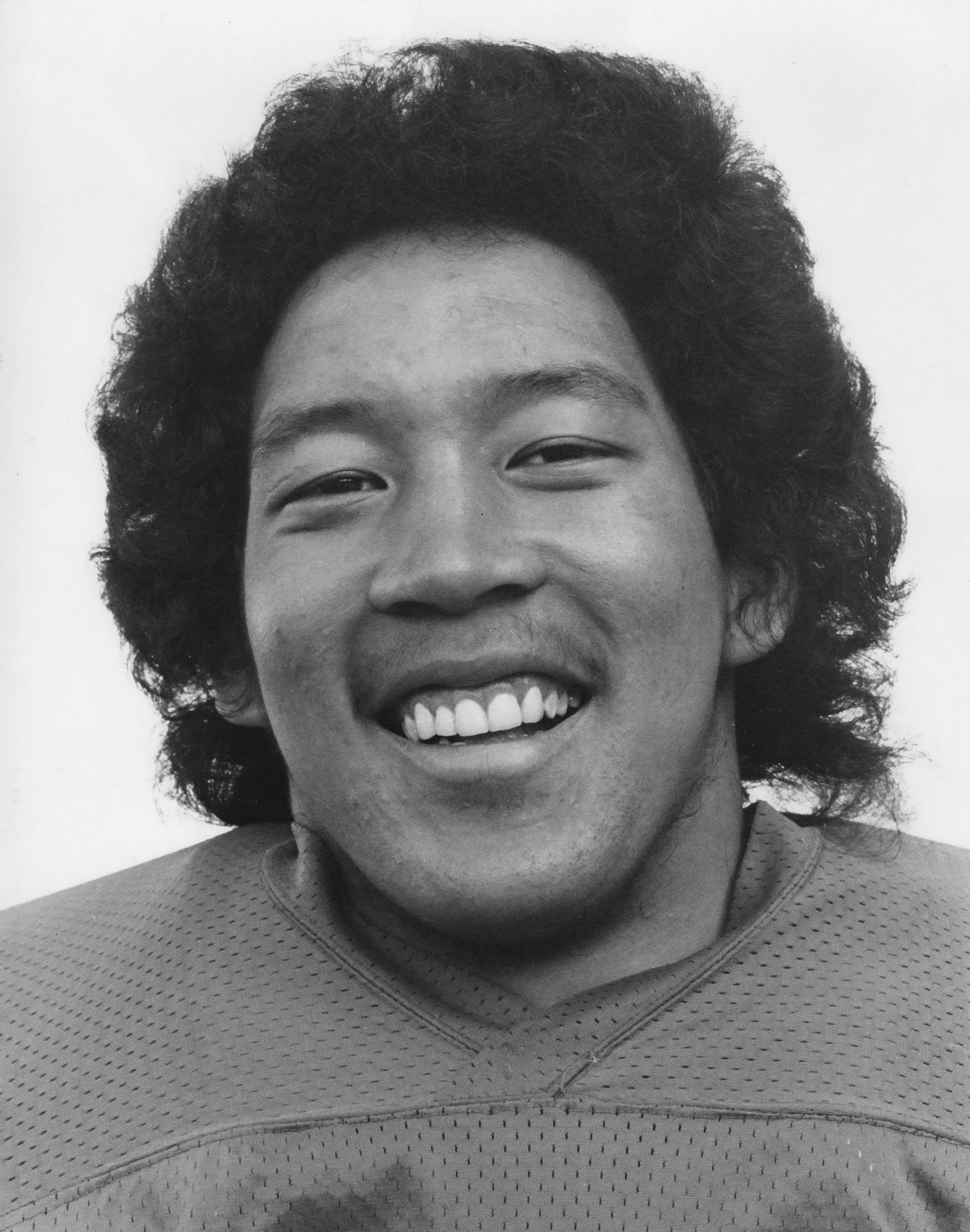

Bruce Harrell, ’81, ’84, talks about football, family and Seattle's transformation in an exclusive Q&A.

By Mike Seely | January 27, 2024

On a frigid Friday in early January, with the wind chill pushing temperatures into single digits, Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell walked into a Founders Hall conference room on the campus of his alma mater, the University of Washington.

Cold as it was outside, a greater chill was about to take hold with word that head football coach Kalen DeBoer would be leaving to take the same job at the University of Alabama, mere days after the Huskies came up short in their bid to earn the program its second national championship.

The news would hit Harrell, ’81, ’84, harder than most. He was a starting linebacker and academic All-American for Don James’ Husky squads in the late ’70s, and his wife, Joanne, ’76, ’79, sits on the university’s Board of Regents. Meanwhile, their daughter, Joyce, works in recruiting for UW football.

A product of the Central District, Garfield High School, and UW’s law school, the biracial Harrell could have continued his career as a successful lawyer and gone anywhere in life. Instead, he has chosen to be a public servant in Seattle, where in 2021 he became the city’s first Japanese American and second African American mayor after an impressive city council tenure.

Harrell recently sat down with University of Washington Magazine to discuss his ongoing ties to the University and how it factors into his role with the city. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

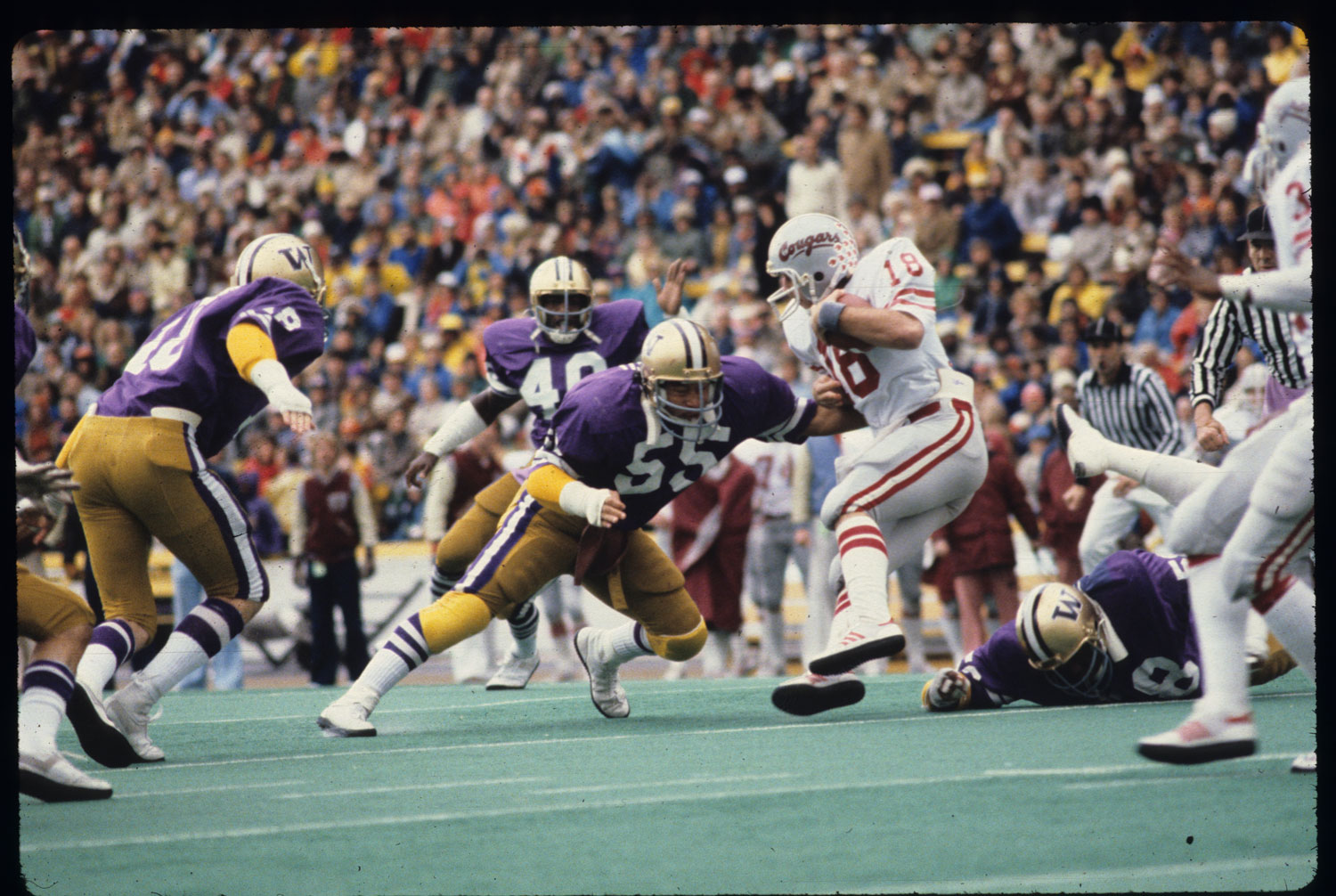

Bruce Harrell, #55, takes charge in a game against the Washington State Cougars. Photo courtesy of UW Athletics.

UW Magazine: You watched the national championship game, I assume?

Mayor Harrell: I was there.

What did you go through emotionally during that game?

I was also at the Sugar Bowl and I saw that great victory as well. What I think we’re forgetting is they were the Pac-12 champs, they were the Sugar Bowl champs, and they made it to the national championship. We just weren’t the national champs.

I still feel the impact of the loss because that was not our best game. I’m a little more bitter because I know that we could have won that game. But, once again, we should be very, very proud of this team, this administration, the coaches. But it’s a tough loss to take because that game was within our grasp, particularly in the third quarter.

You play the long game. This is a great accomplishment. You just keep plowing ahead, but this was a tough pill to swallow.

Let’s rewind several years. You’re at Garfield High School and you have the opportunity to go to any number of colleges. Why’d you choose the UW?

I visited Stanford and then announced I was likely to go to Stanford because of its academic record. I took a trip to Harvard and was very impressed with what I saw there. But when I started spending time at the University of Washington beginning my junior year of high school, going to football games and meeting Don James and Jim Lambright, they not only became coaches, but also mentors and friends. And I explained to them then that what inspired me wasn’t fame or money. It’s just I wanted to really look back at what I called home and wanted to be the best public servant I could be. That was my long-term goal.

They explained to me the benefits of sticking around town, and they also believed in the whole ecosystem around us, which was composed of nonprofits, a great academic institution, these great companies which now have a global presence throughout the world. They explained to me things, at 17, 18 years old, that I didn’t really think about. Coach James really was a visionary and he said, ‘You’re here where all the action should be.’ I fell in love with the vision of growing with a great city, and indeed, this city grew with me in the last 30, 40 years.

His demonstration of that visionary leadership is that even when I finished football, he continued to help me and advise me, as did Coach Lambright. They impressed me by saying that in choosing to go to the University of Washington, they would stay with me. And they did.

Did your kids go to the UW?

My oldest did. He was a walk-on on the basketball team. My other two did not, but my daughter, Joyce, was on a basketball scholarship at Boise State and got her master’s degree there. She worked briefly for the Miami Dolphins; she was there when (former Husky running back) Myles Gaskin was there. She worked here under Coach [Jimmy] Lake, and when Coach Lake left, she was retained by DeBoer.

Did you meet your wife at the UW?

Yeah, she was a couple of classes in front of me and her sister and brother were closer to my class. So we met here as students and ended up working for the phone company together after graduation. I was an attorney in the law department and she was a VP in one of the divisions. She worked on the 31st floor and I worked on the 32nd floor, but her office was a lot nicer than mine.

This place, Founders Hall, is special to you and Joanne for a couple reasons: It’s the home of your endowment, which is connected to the Liberty Project. Can you talk a little bit about how your relationship with the Foster School of Business has evolved?

Here in Seattle and the Pacific Northwest, we’re known for our global leadership in terms of large companies. But I think equally important — dare I say, even more important — is the small-business infrastructure. Many people come here for small-business development and entrepreneurship. When you have large companies like we have here, if done correctly, it provides the perfect ecosystem for small- and medium-sized businesses to develop. Here in the business school, they foster entrepreneurship, innovation.

On my African American side of my heritage, my Black grandfather had come up here as a businessperson from New Orleans to establish a small business. He was quite successful. He owned commercial real estate back in the 1950s as an African American man. Same thing with my Japanese grandfather — he’d come here and owned several flower shops. They hired people from their community.

At the University of Washington, they have a unique opportunity that they are capitalizing on, teaching and nurturing entrepreneurship and small businesses. That’s something Joanne and I are passionate about.

Whenever I walk around campus, I notice a new wrinkle or new building I hadn’t seen like two months ago. I could say the same thing about a lot of neighborhoods in Seattle, including where you grew up, the Central District. It’s undergone quite a transformation. If you look at the city right now, how does that progress strike you? What’s been good about it and what have we maybe missed that we can try and reclaim?

That’s a great question. I tend to be nostalgic. I tend to look at areas and have to close my eyes to envision what once was there. A lot of people don’t realize there was once a rodeo near Seattle University’s campus, and as a child, I remember seeing the rodeo. The fact of the matter is that cities evolve, that growth is good, and it has to be managed.

While I do miss many of the assets that were once there and the simplicity of a neighborhood that was extremely affordable to people of all income levels, I recognize Seattle has become a very wealthy city. That’s both good and bad. We have to be more intentional about allowing a barista or food-service worker or teacher or police officer, we have to make it more affordable for them to live here. So, we have to bring in density, smaller units. We have to look at where our zoning laws allow us to be more creative.

I do get nostalgic and think about the good old days, but I have to realize the world is changing around us and we have to change with it. That’s not to say we can’t have great assets that bring us together as a community. When I think about nostalgia, I don’t think so much about the brick-and-mortar as I do about the simple fact that as a child, I could walk down the Central District and knew everybody. With neighborhoods, how do you still develop that common touch? You had that cultural connectivity, and we can still recapture that in neighborhoods as we continue to embrace new people and new structures.

Narrowing in on the U District, it almost looks like downtown Bellevue with all the construction and housing going up. Then again, the Ave is kind of still the Ave. People who grew up here appreciate that, but some people are like, ‘Whoa, what’s that street down there?’ What are your memories of the Ave and the U District when you went to school here?

With the Ave, we have been very intentional about trying to preserve its character. I’ve been very vocal as mayor saying that density is good, but not everywhere. Having said that, some of my most fond memories were literally walking there with friends, many of whom were athletes, going to different places and getting hot dogs and pizza and enjoying the bookstore and walking around. It was just always a fun thing to do. Small businesses there, being able to buy something — what do the kids call it now, merch?

I’m hopeful and prayerful that the athletes playing today, they have the benefits that I had, and that is the friendship of the people they play with. They are strong to this day. I met a young man named Doug Martin. He was a big defensive lineman and he’d come from Fairfield, California. During two-a-days, I told him I like to fish and he told me he liked to fish, so after football games, we’d go down to the pier and fish off the pier, behind the crew house. To this day, we still fish. With the NIL [name, image and likeness] and transfer portal, that could be lost.

What kind of values that you picked up at the University of Washington do you carry into your mayorship and life today?

A lot of them. One is what Coach James said: There’s no substitute for hard work. The difference between people is those willing to put in the gym time, the film time. When I would think, even my freshman year, when I lettered on special teams, after the game, I’d have an abundance of energy. I’d work out for hours. I’d sometimes run the stadium when they were cleaning out the stadium. To this day and when I was on city council, my goal has been to outwork everybody.

Bruce Harrell — still a council member at the time — orates at Seattle City Hall. Photo courtesy of Seattle City Council.

Do they still let you in Husky Stadium whenever you want to run stairs?

No, they invented something called the Stairmaster and you have all these treadmills. I tell my staff we have to out-hustle everybody. Second thing was my attitude, that’s something you can control. That came right out of Jim Lambright and Coach James’ playbook. I tell my children, ‘When you walk in a room, you want to light it up. You don’t want to suck all the energy out of it. You want to be the positive battery.’

The third piece that Coach James, it took me a while to understand what he was saying, is that he would say, ‘What I say to the press, ignore it. What matters most is what I say in the locker room, what we do on the field when there’s no one around.’ What I try to tell my team is that people will say things in the newspaper that could be true or untrue. Don’t let any of that affect what you’re doing inside the locker room. That’s a metaphor for the sixth floor and seventh floor of city hall. Particularly with social media, it makes it more of a point to surround yourself with people to ensure that you’re doing the right things.

The University of Washington is its own entity and force in its own right, but it’s also part of the city. What specific interactions does your office have with the UW throughout the year? What are some of the things that have become points of intersection?

Coach DeBoer, he’s been one of the best in terms of making sure they are accessible and working with us [former football players] to help the program. Other coaches had more of a walled-off strategy. When they are recruiting athletes and have events, I’m sometimes asked to come in and share what Seattle is like, what life after football could be. You get to befriend the young men and their families. They really want to know how impactful this city can be, so I’m often called upon to go to different social events to impress upon the family that they have a mayor who cares about these student-athletes.

I would not be mayor were it not for the University of Washington. It was the relationships I developed here as a student-athlete that allowed me to build the capital to do what I wanted to do.