A race to clean energy A race to clean energy A race to clean energy

The UW’s Clean Energy Institute is speeding the development of next-generation technology and supporting the experts who will create it.

The UW’s Clean Energy Institute is speeding the development of next-generation technology and supporting the experts who will create it.

As Hurricane Maria tore through Arecibo, Puerto Rico, in 2017, Miguel González-Montijo hunkered down at home with his family. They were no strangers to hurricanes. Just two weeks earlier, a Category 5 Hurricane Irma had skirted the island, demolishing homes, causing floods and knocking out power for more than a million people. And now Maria, with wind speeds up to 155 mph, was hitting Puerto Rico dead-on. Arecibo, with its peaceful golden beaches and lush hills rising behind it, was now a maelstrom of howling wind and driving rain.

Human-caused climate change was already leading to warmer oceans, enabling more frequent and more powerful hurricanes. But González-Montijo wasn’t thinking that far ahead—he was wondering when Puerto Rico’s power grid would recover and trying to distract himself by studying for graduate school entrance exams by lamplight. After earning his bachelor’s in engineering at the University of Puerto Rico at Mayagüez, he was deciding between finding a job or pursuing graduate studies.

Once the winds subsided, he and his family went outside to survey the scene. “Everything was destroyed,” he says. “The streets were filled with trees, light posts and electrical cables.” It soon became clear just how bad the situation was. A full 97% of Puerto Rico’s electricity is generated by fossil fuels and must travel over rugged mountains and through dense jungle en route to its customers— and now, that electrical grid was in shambles. It would be 2 1/2 months before González-Montijo’s family got their power back; others waited nearly a year. It was the longest blackout in U.S. history.

In the meantime, González-Montijo decided to pursue a graduate degree in civil and environmental engineering. He knew local jobs might be scarce as Puerto Rico slowly recovered. And there was a lot he still wanted to learn—hoping to eventually return home with skills to help make Puerto Rico more resilient.

“I’ve been a professor for a long time, and I’ve never seen the motivation of the students circulating around the Clean Energy Institute.”

Dan Schwartz, CEI founding director

Accepted to schools across the country, he chose the University of Washington for its many cross-disciplinary research opportunities. He’s now on the cusp of earning his doctorate. His intellectual curiosity led him to clean energy, and he found a community of people—in fields from electrical engineering and public policy to chemistry and physics—who shared his growing passion. At the heart of this passion is the UW’s Clean Energy Institute (CEI).

In 2013, the UW launched CEI with support from the state of Washington; Gov. Jay Inslee, ’73, championed the investment. The institute’s mission is to speed the transition to a scalable, equitable clean energy future by advancing the next generation of solar energy and battery materials and devices, and improving their integration with the power grid. It was good timing: That same year, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released a daunting report, warning of the consequences of unchecked carbon emissions. From the get-go, CEI would operate with a sense of urgency. Over the past decade, a combination of federal, state and private investment has bolstered its mission.

In 2017 CEI opened its Washington Clean Energy Testbeds, high-tech labs where researchers and industry partners can use top-of-the-line equipment to develop clean energy technology. Thanks to philanthropic funding, the Testbeds recruited faculty and staff with deep industry experience, whose expertise can help innovators move technologies quickly from research to impact. Students of all degree levels can conduct clean energy research and development side-by-side with industry. And each year, dozens of graduate students gain fellowships and professional experiences through CEI, preparing them for the complex, multidisciplinary clean energy workforce. González-Montijo is one of them.

“I’ve been a professor for a long time, and I’ve never seen the motivation of the students circulating around the Clean Energy Institute,” says Dan Schwartz, Boeing-Sutter Professor of Chemical Engineering and CEI founding director. “They know we’re putting them in a position to have an impact.”

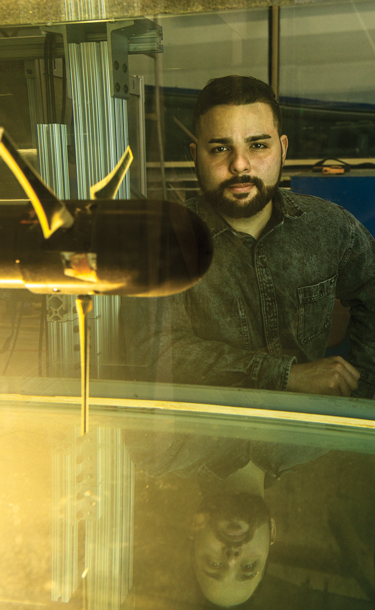

In his first year, González-Montijo learned that marine energy combined with microgrids (localized power grids) could help places like Puerto Rico recover from natural disasters. He got involved with a research project to more efficiently and economically produce marine hydrokinetic turbine blades—essentially, propellers that harness energy using the natural movement of water. But lab research alone won’t get clean energy technology out into the world. It requires cross-disciplinary collaboration and testing facilities to make sure it can be produced in large quantities. It also benefits from the levers of private investment and public policy support.

Miguel González-Montijo’s research, in the lab of Mechanical Engineering Professor Brian Polagye, focuses on developing cost- efficient, open-source turbine blades.

González-Montijo saw these benefits when he first worked with CEI, through the Science Policy Analysis Track of the Torrance Advanced Experience Program. In this philanthropically supported role, graduate students contribute to technical policy briefs and white papers for the Washington State Academy of Sciences (WSAS), which helps inform state policy.

As a policy analyst, he worked on a report on decarbonizing Washington’s aerospace sector, which was presented at a WSAS symposium. He also got to hear from the CEO of electric-airplane company magniX and meet with a Washington state senator. Having his expertise valued made an impact on González-Montijo. “If this can happen here,” he realized, “it could happen in Puerto Rico. It gave me hope that one day my voice could matter there.”

González-Montijo went on to earn a CEI Fellowship, which involves learning from industry leaders and doing community outreach. He teamed up with Ricardo Rivera-Maldonado, a chemistry doctoral student and CEI fellow who’s also from Puerto Rico, to produce CEI’s first Spanish-language learning resource: a bilingual climate science fact sheet for K–12 students. They hoped to empower young people to discuss climate change and clean energy with their families and communities. González-Montijo remembers one visit to an elementary school in North Seattle, where a girl who didn’t speak English became fully engaged when he and Rivera-Maldonado presented in Spanish. At a school in South Seattle, a young girl told them, “I want to be a scientist someday,” and began peppering them with advanced questions about geothermal energy.

For this meaningful project, González-Montijo and Rivera-Maldonado were honored with the Clean Energy Outreach & Service Award in 2022.

In addition to several roles with CEI, González-Montijo has been a graduate research assistant for the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), where he has designed and developed a marine turbine blade component that will be open-source and accessible to startups working in marine energy. “Right now, we can’t afford to be selfish,” he says.

Over his UW career, González-Montijo has advanced research in marine energy. At CEI, he’s traded ideas with colleagues and professors in chemistry, electrical engineering and physics. And he’s shared his expertise with people in government, in industry—and in elementary school.

“Not everyone needs a Ph.D. to contribute to clean energy,” he says. “There are a lot of opportunities that allow you to participate in this exciting field.”

“If we were using other sources of energy, perhaps there wouldn’t be such a dire situation every time we get a natural disaster.”

Miguel González-Montijo

After Hurricane Maria passed, González-Montijo remembers the intense humidity that clung to him like a blanket. The smell of shredded vegetation lingered on the air, clean like freshly cut grass. The familiar crickets, owls and frogs stayed eerily quiet the first night or two. Gradually, they reemerged and resumed their nighttime calls. It would take the people of Puerto Rico much longer to begin returning to life as usual.

“If we were using other sources of energy, perhaps there wouldn’t be such a dire situation every time we get a natural disaster,” says González-Montijo. He has hope, though. Clean energy technology is seeing huge advances that could make a difference around the world. In fact, he says, NREL is studying how to best deploy marine and wind power and microgrids in Puerto Rico. And communities there are already starting solar-powered microgrids of their own.

There is one positive that González-Montijo remembers from the aftermath of Hurricane Maria: “It created unity among us. We depended on one another. It brought us all closer together.”

Perhaps a clean energy future will be powered by such a supportive mindset. González-Montijo is doing his part to make this a reality.

Mike Pomfret has been managing director of the Washington Clean Energy Testbeds since they opened in 2017. With a doctorate in chemistry and a background in research and startup leadership, he knows from experience that some of the most innovative companies on the market are startups. “But,” he says, “they tend to have the most financial challenges.” A startup in solar power or lithium-ion batteries might be stymied by the cost of the equipment needed to innovate, test and scale up their product.

That’s where the Testbeds come in. These high-tech labs are open access and available for an hourly fee, so startups can access industrial-quality equipment and staff scientists’ expertise to develop their technology. At the main Testbeds site, an unassuming former warehouse on the outskirts of University Village, you’ll find safety-goggled scientists using equipment like a 30-foot roll-to-roll printer for solar cells and batteries; devices that replicate the sun’s power to test solar technology; and a digital simulation of a power grid.

Companies that use Testbeds technologies get to keep their intellectual property, too. “That brings people in,” says CEI director Dan Schwartz. “This has never been about maximizing University revenues. It’s about maximizing our ability to have an impact on students and on companies that might be able to reduce carbon emissions faster.”

Students also benefit from access to the Testbeds and proximity to industry. Hannah Contreras, a chemistry doctoral student and CEI Fellow, chose the UW for its “clear, established infrastructure for clean energy research.” In her Energy Materials, Devices and Systems (EMDS) course, held at an on-campus Testbeds location focused on research and training, she made her first solar cell—a task she now does regularly in her research on next-generation solar cells. And through the Tech Due Diligence Track of CEI’s Torrance Foundation Advanced Experience Program, created thanks to philanthropic generosity, Contreras advises climate tech investors as they evaluate companies seeking funding.

“Our students are hungry to contribute to a clean energy future,” says Cody Schlenker, an EMDS instructor and Washington Research Foundation Innovation Associate Professor of Chemistry and Clean Energy. “They’re ready to take ownership and fix the problem. Our goal is to help equip them to do it.”

Soon, the CEI Testbeds will have a new home in Portage Bay Crossing, the UW’s new knowledge community being developed west of campus. Learn more: uw.edu/portagebaycrossing