In 1934, Wolf Bauer, an engineering student obsessed with skiing and exploring the mountains of Washington, approached the board of Seattle Mountaineers Club with a radical proposal. He wanted to teach climbing techniques to his fellow club members using what he had learned from books he had ordered from Europe.

What made this request controversial was that the seasoned climbers at the time closely guarded their techniques. Bauer, ’35, hoped to do the opposite. Studying German climbing books, writing letters to European climbers, and testing and refining their advice, he developed some new lessons that he was eager to share. “We were not climbing safely, we were not skiing safely,” he said in a 1974 interview with Harry Majors, ’74, for a UW history project. Bauer watched his friends take unnecessary risks and he knew that with advice, equipment and practice, they could do better.

Born in Germany in 1912, Bauer spent his early childhood in the Bavarian Alps. His family moved to Seattle in 1925. Already an avid skier in 1929, he was one of three Seattle Boy Scouts selected for free membership in the Mountaineers, a social club built around a passion for the outdoors. As a scout leader in the early ’30s, he trained senior scouts in the fundamentals of climbing—using a glacial boulder in Wedgwood for practice. Bauer was the first person to climb Mount Rainier via the more difficult north-side route along Ptarmigan Ridge.

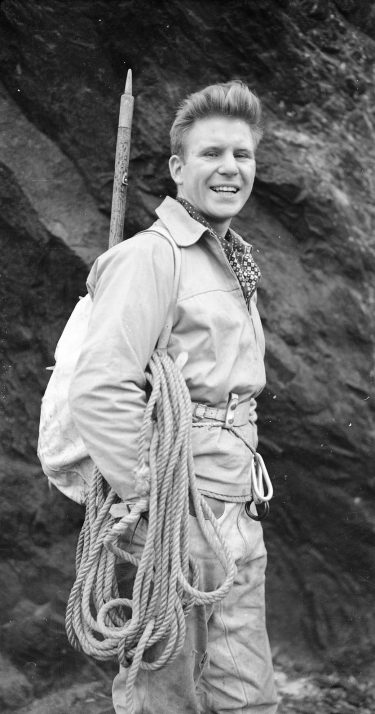

Wolf Bauer

But learning and developing skills was a challenge, especially since the senior climbers believed you had to learn it on the mountain through trial and error. “I was a young upstart. I was still a teenager. And I was just starting at the University,” said Bauer. The fact that the seasoned climbers kept to themselves didn’t make things any easier. “It was very hard to break into these cliques,” he said. But once he understood how they climbed and what equipment they used, he was surprised to find that “it was very amateurish.”

In the end, the club’s leaders decided to let him teach mountaineering skills the following year. The decision forever changed mountaineering in the West. In the first basic skills class, Bauer introduced 19 newer climbers like Lloyd and Mary Anderson—the couple who would go on to found sporting goods cooperative REI—to a safer, more elegant way to climb.

“I was just a jump ahead of my class,” said Bauer, describing those first days of teaching. He practiced by himself and then, sometimes just a few days later, would teach what he figured out to his students. “I lived in the University District and I would be out after school practicing the rappels on the Cowen Park Bridge,” he said. “Then the next week I would have to go down [to the clubhouse downtown] and teach this rappel.” In fact, Bauer is likely the very first climber to demonstrate a rappel in the Northwest.

“Wolf Bauer was at the beginning of the club’s tradition of passing knowledge forward, teaching the necessary skills and helping define the routes and experience of where to go,” says Mountaineers CEO Thomas Vogl. More than that, he was one of legions of alumni and faculty who shaped the social organization.

From the time of the Mountaineers’ first official meeting 110 years ago and in the century since, UW alumni, faculty and staff have devoted many thousands of hours to the club and helped define key components of Northwest culture: healthy respect for nature, an abiding engagement with the great outdoors, and a passion for preserving our landscapes. Today, with classes, camps, chapters throughout the state, 500 books and guides, 12,000 members, and a mission to protect and preserve the natural resources of our region, the Mountaineers are a force for nature.

A time before trails

More than a century ago, before roads crisscrossed the region, before cords and carabiners, an intrepid group of men and women—teachers, doctors, students and civic leaders—were swept up in the romance of exploring Washington’s wilderness as members of the Mountaineers.

One February day in 1907, more than 100 charter members gathered for one of the club’s first official meetings. They packed the two rooms of the Seattle Chamber of Commerce in the newly built brick and terracotta Central Building on Third Avenue. Trevor Kincaid, a UW entomologist and alumnus from the classes of 1899 and 1900, spoke to the group about an expedition to Alaska. According to an account in the club’s bulletin, he enlivened the science with his quiet humor and anecdotes.

Then, according to the bulletin, the charter members learned of their mission to render public service “ … in the battle to preserve our natural scenery from wanton destruction,” and “make our spots of supremest beauty accessible to the largest number of mountain lovers.” Geologist Henry Landes, the club’s first president and the future dean of geology at the UW, crafted those words. He and renowned photographer Asahel Curtis and businessman W. Montelius Price had just formed the group to explore the mountains, forests and waterways of the Pacific Northwest, and record the histories and traditions of the region.

John Muir, the great American naturalist and founder of the Sierra Club, sent the foundling club his encouragement: “I am with you heart and soul in your work of white icy mountain climbing and all that goes with it.”

One hundred and ten years later, Lowell Skoog, ’78, and a few Mountaineers staffers gather around a table on the second floor of the club’s 17,500-square-foot headquarters at Magnuson Park. An unofficial historian for the club, Skoog has spent thousands of hours studying the organization’s bulletins, poring over its topographical maps and sorting through photographs. He knows some of the earliest Mountaineers nearly as well as he does current club members.

Fred Beckey, ’49, at Cashmere Crags c. 1949, is a legend among climbers for his pioneering ascents.

The charter members took one- to two-day excursions throughout the year, as well as a major trip of two to five weeks every summer, says Skoog. Their very first official outing took place on a Sunday in February, though it was hardly impressive by today’s mountaineering standards. Forty-nine members and their guests—many dressed in their city finery—made their way to Fort Lawton on the north side of Magnolia Bluff and walked through the woods to the West Point lighthouse. After they enjoyed a campfire and lunch, they took advantage of the low tide and hiked back along the beach.

The second outing a few weeks later started with a boat ride to Kirkland and a seven-mile walk along the belt-line road. This was typical of those early day trips, which entailed stepping into the wilderness just outside the city, at the end of a streetcar line or a ferry ride.

But as soon as weather permitted, they made for the mountains. In May 1907, Landes led the climb up the steep hillside of Mount Si. Alida J. Bigelow wrote an account noting that 30 struck out, but 24 reached the summit. A few dropped out early and two stopped after lunch feeling the mountain was too high. But those who persevered “were rewarded with a grand view of the country to the west,” she wrote. “The Sound shown as a line of glimmering silver and the valley winding in and out on its seaward journey was worth all the toil of the morning.”

Later that summer, armed with alpenstocks (long wooden poles with spikes at the tip) and thick wool blankets, they took on Mount Olympus. A group of 65 set out for several weeks of hiking and camping on the peninsula, and a small team of eleven made the summit.

In those early days, Edmond S. Meany, a UW graduate from classes of 1885 and 1889 and a beloved UW professor of history and forestry, lectured on American Indian language and lore. At Landes’ urging, Meany became the second president of the Mountaineers, in 1908. “While thus from boyhood I have dwelt at the level of the sea, my soul has continually feasted upon visions of lofty peaks,” the new club president wrote to the membership. He waxed on: “And now with you, my friends, I am coming into a more intimate acquaintance with the loved mountains, as we build trails to climb their sides and play in their wonderfully beautiful parks, until added strength and a profound enthusiasm enable us to scale their utmost heights.”

Though already 50 years old when he joined, in his 27 years as president, Meany managed to climb the six highest peaks in the state. Alumna Lydia Forsyth offered a description of the old professor: “On the trail he wore a corduroy suit, high boots and a wide-brimmed ranger style felt hat.” She described him as “a benign and brooding presence, lending dignity to any occasion,” whether it was a meeting, a banquet or a campfire. And he set standards like “leave a campsite better than you found it,” which today has evolved into “leave no trace.” In fact, Meany should be credited for setting much the club’s personality, traditions and ideals.

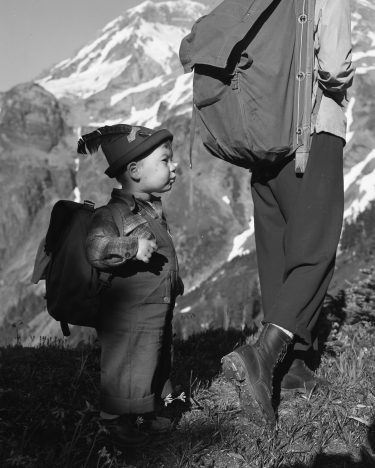

Joan Burton poses near Mount Rainier c. 1958, Today the UW retiree writes guidebooks featuring great hikes with children.

The club formed at a time when people in the West, particularly urbanites, began to see their environment as something other than a storehouse of raw materials ready to be extracted, says UW history professor John Findlay. Both the Sierra Club in San Francisco and the Mazamas in Portland had formed in the 1890s and their members regularly ventured north to explore the Cascade Range in Washington, where it is at its most spectacular.

“These groups formed around the notion that mountains were a source of recreation and inspiration that needed legal protection” in ways like designation as national parks, says Findlay. They could also see economic advantages to protecting these areas. “To be fair,” says Findlay, “city boosters often latched on to mountains and other natural attractions as part of their tourist hinterlands, a way to attract visitors and increase commerce.”

A new era for ‘new women’

Many who felt called to the mountains and the adventure they offered were women—who comprised nearly half the charter members of the Mountaineers. Christy Avery, ’01, ’04, a former graduate student of Findlay’s and now a historian with the National Park Service, was so intrigued by the women in the club, she turned her curiosity into a major research project.

Growing up in Kirkland, Avery was no stranger to the call of the landscape. In her family, explorations typically involved a “drive to Mount Rainier, a walk on a nature trail, jelly sandwiches and then home.” But as a teen, she started hiking with her friends. Their unstructured trips—driving somewhere, finding a trail and trying to get home before dark—only honed her taste for the woods. “You learned through experience,” she says.

As a history student, she found her love of the outdoors and of history met up in the UW Libraries Special Collections. Digging through mountains of materials including club bulletins and photo albums, she savored the details of the trips, the advice to future adventurers, and the accounts of the men and women who were summiting the most challenging peaks. “I was especially struck by women’s participation,” she says. “They seemed to be doing something pretty unusual by being physically active in such a strenuous way.”

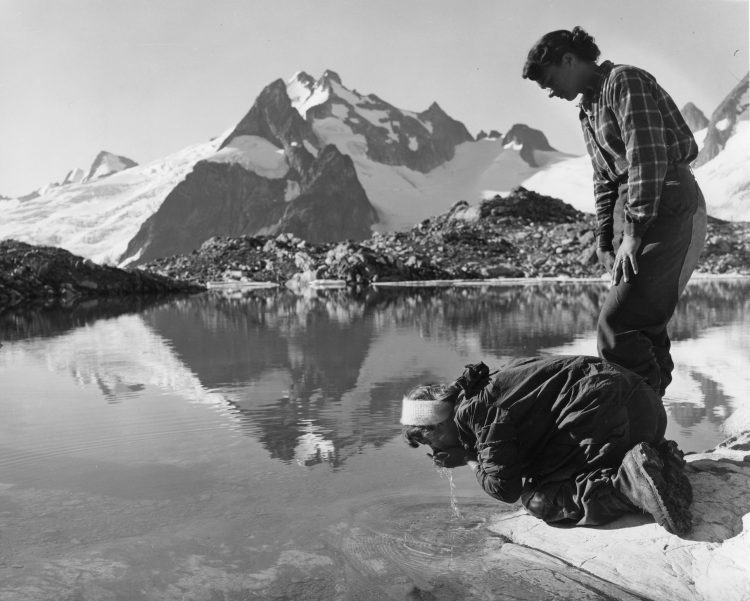

Peggy Stark and Marge Mueller (née McConnell) at White Rock Lakes.

At the time, American women were starting to value physical activity for recreation, but with “civilized” sports like tennis and bicycling. “They weren’t doing glacier travel, generally,” says Avery. “But these women were. They were hiking, camping and climbing. And right alongside the men.

“The more I dug, the more questions came up,” she says. Why were the women so keen to climb? Who were they? Why were men encouraging of the activity? How were the Northwesterners seeing themselves?

The urban Northwest, it turns out, was a progressive place—somewhere single women might want to move, pursue careers, and be engaged citizens. Avery found firsthand accounts and photographs and delightful characters like Mabel Furry, a UW grad from the class of 1911, a schoolteacher, gymnast, and photographer who assembled some of the Mountaineers’ early photo albums.

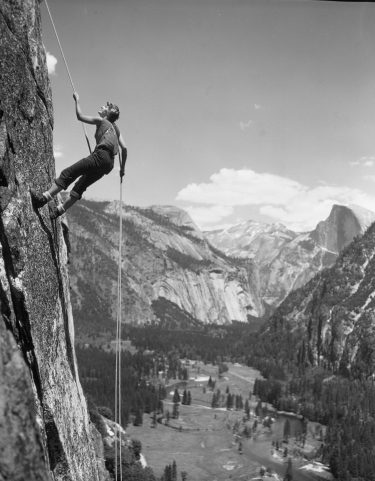

Nancy Bickford Miller, ‘76, climbing in Yosemite, 1955. An accomplished climber, she was a Mountaineer for 64 years, until her death in 2012.

The women who participated back then were overwhelmingly middle class, educated and professional. Most worked outside the home as teachers, librarians and sales clerks. Among them were Bertha Knight Landes (wife of club founder Henry Landes), who would become Seattle’s first woman mayor, and teacher Lydia Lovering (Forsyth), a UW graduate from the class of 1886 who joined the first Mountaineers summit of Mount Rainier in 1909. In the crater, she left behind a pennant proclaiming “Votes for Women.”

UW pioneers

As the Mountaineers membership grew, connections to the University abounded. “One of my favorite characters is Professor Milnor Roberts,” says Skoog. The dean of the College of Mines was a charter member of the Mountaineers, and, in some ways, the father of skiing in the Cascades. In the spring of 1909, he led a group of men and women to explore Mount Rainier’s Paradise Valley on skis.

“That outing marked the beginning of recreational skiing on Mount Rainier,” says Skoog. Roberts’ account of the adventure, titled “A Wonderland of Glaciers and Snow,” was published in National Geographic a few months later, and provided the country with its first view of the national park as a winter playground.

“I also get a kick out of Carl Gould, the architect,” says Skoog. Gould helped plan the layout of the UW campus, was a professor, and designed Suzzallo Library as well as the original Seattle Art Museum and the Olympic Hotel. He also designed the Mountaineers’ Snoqualmie lodge and the first rock shelter at Mount Rainier’s Camp Muir, where people intent on summiting could spend the night. “From Gothic libraries to small cabins,” says Skoog, “Talk about range!”

Professor Milnor Roberts, an avid skiier and charter member of the Mountaineers, crosses campus.

The Mountaineers’ history offers many UW characters to explore, says Skoog. But he would be remiss not to mention Lloyd Anderson, who grew up in Pierce County and graduated from the UW in 1926 with an electrical engineering degree. The story goes that Anderson didn’t much enjoy his job with Seattle Transit, but in 1929 he discovered an outlet with the Mountaineers. He and his wife, Mary, became weekend regulars on the region’s trails. It was only natural that their interests led them to the club’s first-ever climbing course in 1935. Wolf Bauer taught them to trade their alpenstocks for ice axes and introduced them to a world of useful sporting goods.

Eager to find an ice ax of his own, Anderson scoured Seattle for supplies, finally locating one at a hardware store. However, once he arrived at the store, he found the tool to be inferior and overpriced. Ordering from a European catalogue, Anderson procured an ax from Austria for a mere $3.50. So pleased was he with his order, he started buying supplies for his friends and fellow Mountaineers, seeding what would become Recreational Equipment Incorporated.

Jim Kjeldsen, ’73, author of “The Mountaineers, a History,” recently wrote an account of the early days of REI as they unfolded in the Andersons’ living room: “A visit to the Anderson home meant you were liable to be seated on a crate, bearing a European postmark, that had arrived filled with ice axes, crampons, pitons, and carabiners.”

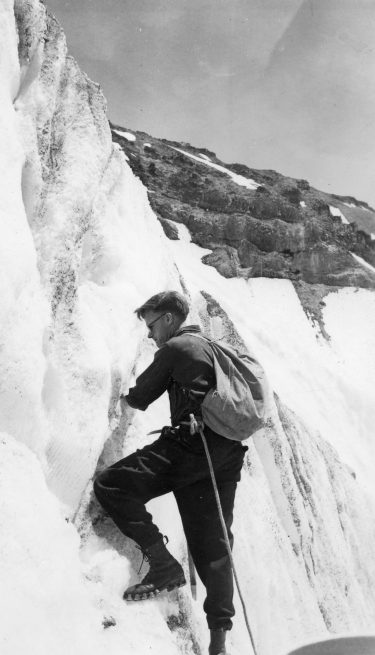

Lloyd Anderson, ’26, founder of REI and lifelong Mountaineer.

Lloyd Anderson also taught and inspired dozens of young climbers who went on to be world famous for their summits. Fred Beckey, ’49, made climbing history at 15—as one of the first to summit Mount Despair along with Anderson and several others. In between peaks, Beckey studied business administration at the UW. But he lived to climb.

Today, though he does little to promote himself, Beckey is famous among climbers worldwide for his first ascents. Locally, his Cascade climbing guides (published by the Mountaineers) are lovingly known as “Beckey’s Bibles.”

Now 94, Beckey is still out enjoying the mountains—and inspiring others. In January, he was featured in National Geographic Explorer, and the documentary “Dirtbag, the Legend of Fred Beckey,” is due out in theaters this summer.

Lloyd Anderson died in 2000 at age 98. Mary Anderson died in March at 107. “Maybe it’s proof about mountaineers living long lives,” says club CEO Vogl, who once worked at REI as a senior vice president. The cooperative now boasts more than 6 million members, more than 140 stores and an online catalog. Members still receive dividends. The Andersons weren’t just the fairy godparents for Washington’s climbers, but also for the runners, trekkers, skiers, kayakers and campers, and not just here, but all over the country.

Preserving and protecting

Wolf Bauer’s passion for skiing and climbing spread to boating (first with foldboats and then with kayaks) which then led him to waterways. When it became clear that Green River Gorge, a 12-mile, river-cut rock canyon, might become clogged with utility dams in the 1960s, Bauer led the fight to protect it. He also helped save other waterways including portions of Palouse River and the Puget Sound shoreline.

He had tapped into the current of conservation that ran through the club from its founding days. The earliest members tangled with timber and mining interests over the forests on the Olympic Peninsula and made a direct appeal to President Theodore Roosevelt in 1909, which resulted in the creation of the Mount Olympus National Monument. Nearly 30 years later, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt designated the 880,000-acre Olympic National Park. Then in 1956, Mountaineers members convinced the National Park Service to end logging there.

They also fought successfully to keep Mount Rainier National Park from being riddled with roads, and were central to the development of Washington’s state park system.

A young outdoor enthusiast c. 1950.

In the 1950s, club members helped start a North Cascades Conservation Council, which was eventually headed by UW biochemistry professor Patrick Goldsworthy. The payoff was the North Cascades National Park Act signed by President Lyndon Johnson in 1968. “It took a lot of wheeling and dealing to get that to pass, but it a way it kind of revived the conservation movement,” says Skoog.

That was around the time that Skoog and his brother were teaching themselves to climb. “We climbed Mount Rainier early on,” he recalls. “I think I was about 18 or 19. And we pretty quickly got acquainted with the North Cascades.”

He had been inculcated in alpinism by his parents, though. His father was a ski jumper and, with Skoog’s uncle, had a role in establishing the Crystal Mountain ski resort. Skoog joined the Mountaineers as a young adult. “I had two interests,” he says. One was to get access to the club’s library of maps and guides, which it turned out he could have had even without a membership, and the other “was to find out where the Mountaineers would be on any given weekend. Then I would go somewhere else.”

The issue of hundreds of Mountaineers overrunning a park or trail on the same adventure isn’t so much the case these days. And Skoog has found another calling: collecting and curating the history of the organization, with a particular interest in skiing.

Members like Skoog are heirs to Wolf Bauer’s legacy: teaching, guiding and preserving. A fellow member, Steve McClure, ’81, is driven to share his love of exploring wild spaces and improve the safety of his fellow hikers and climbers. He teaches classes on how to navigate the backcountry with the help of modern tools. A CPA and partner with a company that advises companies in the tech, venture-funded and real estate fields, McClure is also the at-large Mountaineers author of “Guide to 100 Peaks in Mount Rainier National Park.” “These are really serious mountains around here,” he says. With the weather, snow and challenging landscape, planning and preparing are key. “Part if it is technique and part of it is just being able to find your way around.”

Another author, Craig Romano, ’94 and ’97, developed his taste for outdoor writing with a “Go Take a Hike” column for The Daily. History classes from professors like Findlay, paired with a few elective classes in forestry, an excellent grounding for his future career.

Having grown up on the East Coast in Thoreau country and about three miles from Robert Frost’s farm, “I’ve always been drawn to conservation,” says Romano. “I joined the Mountaineers as soon as I moved out to Washington. I love the natural world and I believe in giving back.”

Today he gives back to his fellow hikers through guidebooks for the club’s publishing arm, Mountaineer Books, with more than 30 titles. His first project, in 2005, paired him with photographer Ira Spring, writer Karen Sykes and UW Botanist Arthur Kruckeberg—three icons in Northwest outdoor guides. In updating “Best Wildflower Hikes,” Romano was working with his heroes.

Romano relies on the backcountry for his sanity and sanctity, he says. “But I know they’re not there for me. They’re there to preserve species, ecosystems and habitat.”

He sees new threats, like the recent executive order to review the status of lands designated as monuments under the Antiquities Act. That might include the 195,000-acre Hanford Reach in Eastern Washington.

It is time to be more vocal—to spread the word on how parks and wilderness areas came to be and what people must do to safeguard them, says Romano. “So much effort and political will went into protecting them in the first place.”

Last year, the Mountaineers Club advocated to protect 30,000 acres of public land, and more than 1,600 Mountaineer volunteers taught classes to 2,500 people, notes Romano. “We have an obligation to be guardians, stewards and advocates for the trails and lands that have given us so much enjoyment.”

Top image: Climbing Paradise Glacier in Mount Rainier National Park c. 1911. The image comes from Asahel Curtis, a co-founder of the Mountaineers Club.