A Grimm tale A Grimm tale A Grimm tale

Who were the Brothers Grimm? Ann Schmiesing explains the real-life fairy tale of the German authors.

By George Spencer | June 2025 issue

Once upon a time, two boys named Jacob and Wilhelm lived in a lovely home. But when their father suddenly died, the boys and their mother were cast out. Forced to live in an almshouse, the sons worked hard. They became scholars, and luckily for Germany and the rest of the world, the tale of the Brothers Grimm has a happy ending.

Their collection of folk stories “Kinder- und Hausmärchen” (“Children’s and Household Tales”) was first published in two volumes in 1812 and 1815. The most translated work of German literature, it went through seven complete and 10 abridged editions in their lifetimes, growing with each new version to ultimately include 210 stories.

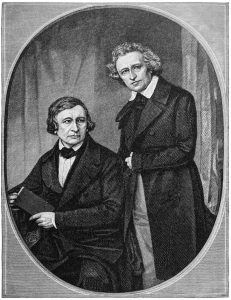

Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm were close-knit. Jacob, who was shy compared to his sociable brother, moved in with Wilhelm and his wife after their marriage.

What drove them to share such gleefully ghoulish yet morally uplifting tales is as surprising as finding a wolf snuggling in Grandmother’s bed. “They were motivated by a desire to promote a sense of German heritage at a time when Germany was not a unified political entity. They felt it would help Germans have a sense of identity at a time when they were still politically fragmented,” says Ann Schmiesing, ’91, the author of “The Brothers Grimm,” the first English-language biography of the duo in 50 years.

It’s a myth, writes Schmiesing, a professor of German and administrator at the University of Colorado-Boulder, that these literary nation-builders trekked to humble villages where peasants shared the stories. Instead, the brothers mostly heard them from upper- and middle-class German women.

The surname Grimm translates as “wrathful.” During their half-century collaboration, they revised the fairy tales in ways that further accentuated their violence, she says. “But there tends not to be gratuitous violence or gruesomeness in the Grimms’ fairy tales. It’s often to teach a moral lesson, a punishment for wicked behavior,” she says. They did, however, bowdlerize sexual content from some stories.

The inseparable brothers worked in studies in Wilhelm’s house at mahogany desks surrounded by bookshelves, heaps of manuscripts and curiosities such as an Egyptian statue, shells, stones, fossils and sculptures of a bear and a lioness.

UW alumna and UC Boulder professor Ann Schmiesing recently wrote a biography on Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm.

While both men died before Otto von Bismarck unified Germany in 1871, the sociable Wilhelm and Jacob, a bachelor who lived with Wilhelm and his wife, were united in their academic passions. They were librarians, linguists and civil servants who also wrote about mythology and legal customs. Their final project, the monumental “Deutsches Wörterbuch” dictionary, reached the letter D when Wilhem died in 1859 and thanks to Jacob’s efforts made it to F before his passing in 1863.

“If you go beyond the global impact of their fairy tales, today’s depictions of the Middle Ages in popular media owe a lot to the fascination with medieval life the Grimms ignited,” says Schmiesing.

She counts among her favorite Grimms’ tales “Rumpelstiltskin” and “Hans My Hedgehog,” a story of a man who wishes for a child even if it is a tiny, spiny beast. He gets his wish, sort of, when his wife delivers a baby who is a hedgehog from the waist up and human below. After riding a rooster into the world to seek his fortune, Hans survives a fiery ordeal, wins the princess, and if they have not died, then they are still alive today, for that is how Grimms’ tales ended in German instead of the “happily ever after” translation.

Why do fairy tales have universal appeal? “They’re a space where it doesn’t matter what society thinks of you, even though you might be the underdog facing enormous challenges or adversity,” she says. “In fairy tales through hard work, the help of a benevolent helper, and a bit of magic thrown in, you will prevail.”

When asked if Disney, which has made 16 feature films based on fairy tales, has ever sought her as a consultant, Schmiesing says no. But she stands ready to help spin straw into cinematic gold. “If they call and ask,” she says, “I’m here.”