The journey here The journey here The journey here

From land-grant roots to national leadership, Robert J. Jones is shaping the future of public education.

From land-grant roots to national leadership, Robert J. Jones is shaping the future of public education.

Ninth grade was a good year for Robert J. Jones. The son of sharecroppers in Dawson, Georgia, he started high school like most boys in his rural community—taking vocational agriculture classes. But unlike his classmates, he gained the nickname “Professor.”

Jones was a curious kid who loved science and nature. His father, R.J., worked long days. During peanut harvest, he left the house at 6 a.m. and returned well past midnight, coated in Georgia red clay. His mother, Mamie, cleaned the home and cared for the children of the landowner. They had a side business raising hogs. Neither had made it to high school, but they were enterprising, hard-working and adamant that education would come first for their children. “I had a sense of how difficult life was for my parents, but I never went hungry or ragged a day in my life,” Jones says.

Walter Stallworth, Jones’ high school vocational agriculture teacher, noticed a sharp mind beneath the polite demeanor. Dubbing Jones “Professor,” he took him under his wing. He urged him to join the New Farmers of America, compete in livestock and soil judging, and rise to chapter president. When the NFA merged with the Future Farmers of America in 1965, Stallworth made sure Jones attended the first integrated meeting in Atlanta—buying him his first blue FFA jacket so he could show up looking the part. “He became my mentor as well as my instructor,” Jones says. “And he made it clear: I would go to college.”

That early mix of high expectations, hard work and well-timed encouragement set Jones on a path that would carry him from the segregated schools of Terrell County, Georgia to academic leadership on the national stage. Today, he brings the full weight of that journey to the University of Washington, where he serves as the school’s 34th president.

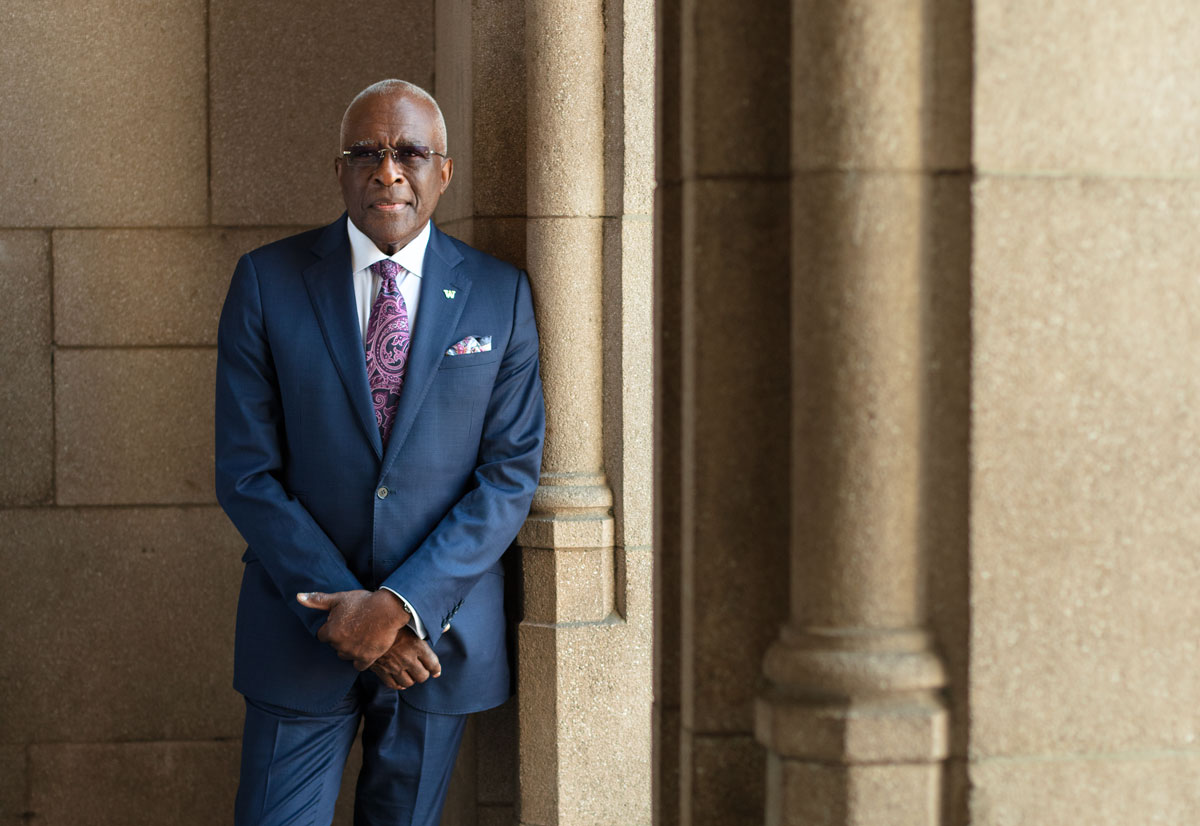

Robert J. Jones, the UW’s 34th president, took office on Aug. 1. He also holds a faculty appointment in the Department of Biology in the College of Arts & Sciences.

Jones chose Fort Valley State, a historically Black land-grant university. Mentor Malcolm C. Blunt took over his guidance, securing internships in soil and forest conservation for his top students. Those summer internships helped Jones pay tuition and deepened his passion for science.

“Mr. Blunt made it clear, ‘You are going to get a Ph.D.,’” Jones recalls. He took that encouragement to heart and earned a master’s degree in crop physiology at the University of Georgia. From there, he pursued his doctoral work at the University of Missouri, working on tall fescue, a grass important for forage and erosion control, in the lab of C. Jerry Nelson.

Jones stood out as a focused researcher and natural leader, says Nelson, who has clear memories of his student nearly 50 years later. After graduating, when Jones was an assistant professor at the University of Minnesota, he presented on his corn research at an agronomy conference. “His was the last paper of the afternoon,” recalls Nelson. “The auditorium was packed with people standing in the back and out in the hall. I barely got in.” Afterward, Nelson overheard students buzzing about the talk. “I was so proud,” he says, adding that he is even more so today. “I made a phone call, gave him an offer and never dreamed it would lead here.”

“If you do public engagement right, you can’t tell where the university ends and the community begins.”

Dr. Jones

Over the next decade, Jones built a research program at Minnesota focused on making corn more resilient to climate stress. His lab thrived with graduate students, technicians and postdocs, all writing grants, publishing research papers and running field trials.

But outside the lab, life in a mostly white city felt unfamiliar. He found community in a local church, and the church choir became his family. That connection led to an audition for Sounds of Blackness, an ensemble rooted in African American musical traditions. For the next 30 years, he performed with the group, touring nationally and internationally, opening for and recording with legends like Prince, Stevie Wonder, Luther Vandross and Quincy Jones, and winning two Grammy Awards.

As he built his lab and his life, Jones resisted moving into administrative roles, determined to fulfill his potential as a research scientist. But in 1984, an opportunity to serve as an academic and scientific consultant for Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s South African Education Program pulled him from campus.

Tutu, believing that apartheid would soon fall, saw an urgent need to prepare young Black South Africans to step into leadership roles in a new democratic society. The initiative brought thousands of Black South African students to American campuses. Jones traveled to South Africa and Namibia each summer for 10 years, helping to identify promising candidates and facilitating their education and training. “That was one of the most profound experiences of my life,” he says. “I know how it feels to be treated as the other. I take great pride in that work. In a small measure, it allowed me to play a role in bringing an end to one of the most atrocious systems in the world outside of slavery.”

Back home with tenure, Jones gradually stepped into administrative roles. “After a few brief meetings, I recognized he was an extraordinary young leader,” says Robert Bruininks, president emeritus of the University of Minnesota. When complex assignments came up, Jones was often his first call. “Few people are as value-centered, as courageous or as skilled at building trust and respect.”

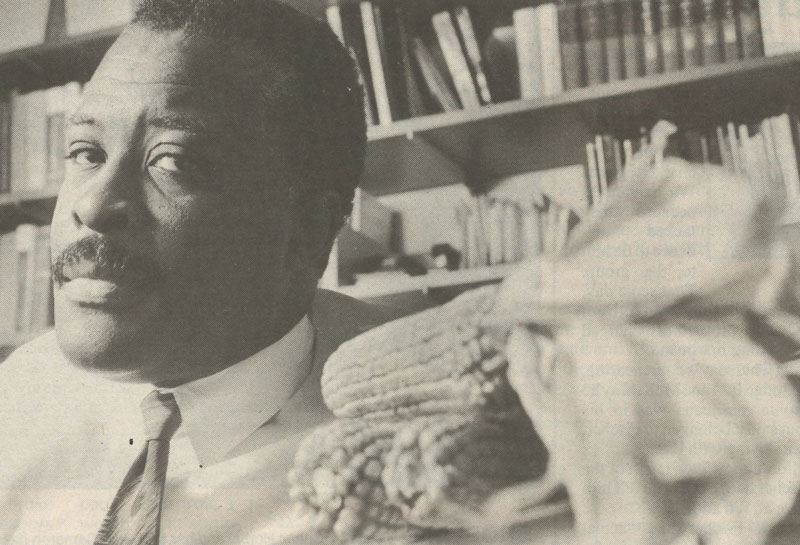

Jones found his voice in Minnesota, presenting his scientific research on corn and joining an acclaimed vocal ensemble. Photo courtesy of University of Minnesota archives.

Jones led a statewide rural and small-town agenda while also working to connect higher education with urban communities. In North Minneapolis—home to Black and Hmong populations—academic research was common, but residents were rarely involved or informed. Jones changed that by leading the creation of the Urban Research and Outreach-Engagement Center, located in a former shopping mall at the heart of the neighborhood. The mission was simple but radical: to flip the model of public engagement. “Now the university partners with the community to solve the problems that matter to them,” Jones says. “The community drives the agenda.”

Opened in 2009, the center was one of the first of its kind. Later renamed in Jones’ honor, it houses programs focused on health, education and economic development. “If you do public engagement right,” Jones says, “you can’t tell where the university ends and the community begins.”

“Few people are as value-centered, as courageous or as skilled at building trust and respect [as Jones].”

Robert Bruininks, president emeritus of University of Minnesota

By the time he left Minnesota, Jones was senior vice president for academic administration. But after 34 years at one school, and serving in a multitude of roles, he was ready to lead a university of his own.

In 2013, he became president of the University at Albany, part of the State University of New York system. It was a major move—1,200 miles east—and over three years, he led a significant enrollment expansion and helped launch two major academic units.

His leadership helped set the stage for Albany to become a more comprehensive public research university. And it didn’t go unnoticed. Before long, the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign—Illinois’ flagship public institution—came calling.

Jones took the helm at Illinois in 2016 and settled in for what would be a transformative nine-year term. He led a $2.7 billion fundraising campaign, committed to covering tuition and fees for all qualified in-state students and launched a new kind of medical school that combined engineering, data science and clinical care.

He blended strategic thinking with humor and optimism. He gained national recognition, chairing the boards of the American Association of Universities and the Association of Public & Land Grant Universities and leading the Big Ten Council of Presidents and Chancellors. Few presidents have held all three roles.

As chair of the Big Ten Council, Jones helped navigate one of the most pivotal periods in the history of college athletics. He played a role in shaping media deals that boosted revenue and secured record-breaking payouts for member institutions. He contributed to the hiring of two commissioners and the expansion of the Big Ten from 14 to 18 schools, which included the UW.

Jones, at that moment, had no idea that after leading Illinois, one of the conference’s founding members, he would soon be leading one of its newest. “It’s been gratifying to help bring the UW into the conference,” he says. And with issues like NIL (Name, Image and Likeness) reform and the House settlement reshaping college sports, he sees a rare opportunity: “a chance to do things differently—to treat student-athletes more fairly and build something stronger for the future.”

By late 2024, as Jones approached his ninth year as chancellor at Illinois, he started to think seriously about what came next. “Some people stay in these roles too long,” he says, adding that he made it clear when he started that he wouldn’t stay more than a decade.

Initially Jones planned to transition to a Chicago-based role where he could focus on key university initiatives. But as news of his decision spread, other opportunities emerged—including one from the University of Washington.

“I wasn’t sure I wanted to start over,” he says. But after interviews with UW regents and leadership, he reconsidered. He saw in the UW a world-class university that aligned with his values: strengths in medicine and public health, a commitment to access and innovation and a strong tradition of shared governance. “The board understood the difference between governance and administration,” he says. “They weren’t interested in being in the weeds. That was the icing on the cake.”

This, he says, is the right final chapter in his academic career. “At the end of the day, I asked myself: Do I still enjoy this work? And I do. I enjoy leading a university. It’s too late to reinvent myself, but not too late to keep moving forward in a place that feels right.”

Now Jones has arrived at the University of Washington carrying a life’s worth of experience: the son of Southern farmers, a plant scientist turned national academic leader, a public servant, a tenor in a Grammy-winning group. His story is one of resilience, curiosity, mentorship and joy.

He tells students to be their authentic selves. To believe in their own promise. To find good mentors and listen to them.

Now, as president, he’s here to do what he’s always done: work hard, lead with heart and lift others up.

Living up to his reputation as a welcoming university leader, Jones was all smiles while taking a break from his UW Magazine cover photo shoot to visit with students and staff. Photo by John Lok.