Pigeon: lost at sea Pigeon: lost at sea Pigeon: lost at sea

This is the story of a determined group of students and a family in a small sailboat who rescued a runaway ocean glider.

By Michelle Ma | December 2025

In May, by the time the location signal came through, the team at the University of Washington’s Student Seaglider Center knew something was wrong. For weeks, their underwater robot, a Barbie-pink glider they had named Pigeon, had been slowing down on its journey toward Hawaii. Now its battery was drained, its signals weak. Somewhere out in the Pacific, Pigeon was still responding, but barely.

“There was a moment where we were like, we might not get this glider back,” says Katie Kohlman, ’24, a doctoral student in oceanography and the center’s chief scientist. “As hard as that was to accept, it was also important to understand that the data it collected—that we already had on our computers—was still worth so much, because frankly this data hasn’t been collected in this sort of fashion before. If we weren’t able to get the glider back, at least we would have this beautiful dataset.”

In a last-ditch effort to recover Pigeon, Layla Airola, ’25, the team’s chief business officer and recent UW graduate in environmental studies, reached out to boating communities and sailing magazines, asking them to spread the word on Pigeon’s situation. A family sailing from Tahiti to Hawaii on their boat Oatmeal Savage, saw one of the articles and volunteered to help recover the glider. Within days, the Van Tol family spotted Pigeon bobbing among the swells.

Only three years earlier, Pigeon and several other seagliders had been gathering dust in storage. Built in the early 2000s to collect ocean data and support scientific research, the instruments had fallen out of use until a group of students revived them in 2022, founding the Student Seaglider Center, a fully student-led and student-run laboratory.

Professor Emeritus Charlie Eriksen, an oceanographer who had helped create the technology, and Kristi Morgansen, professor and chair of aeronautics and astronautics at the UW, donated the gliders to the group. Before Pigeon’s mission, the students had successfully deployed rehabilitated gliders nearly a dozen times, all on one- or two-day missions close to home in Puget Sound. As the students developed the center, they were supported by several advisers, including Fritz Stahr, ’98, the chief technology officer of Open Ocean Robotics, who now volunteers at the Student Seaglider Center.

It’s an amazing opportunity for the students to have these gliders, Kohlman says.

“We’re not letting these instruments be lost in a warehouse somewhere,” she adds. “We’re putting them to use, giving students hands-on experience and contributing to real science.”

Pigeon’s mission was by far the longest and most ambitious of their projects. More than two dozen students pitched in, from setting the glider’s ballast to planning the mission, finding funding and coordinating the launch with outside partners. The collaboration was similar to the shorter missions the students had attempted, but its length and technical considerations challenged the team in new ways.

More than two dozen students pitched in, from setting the glider’s ballast to planning the mission, finding funding and coordinating the launch with outside partners.

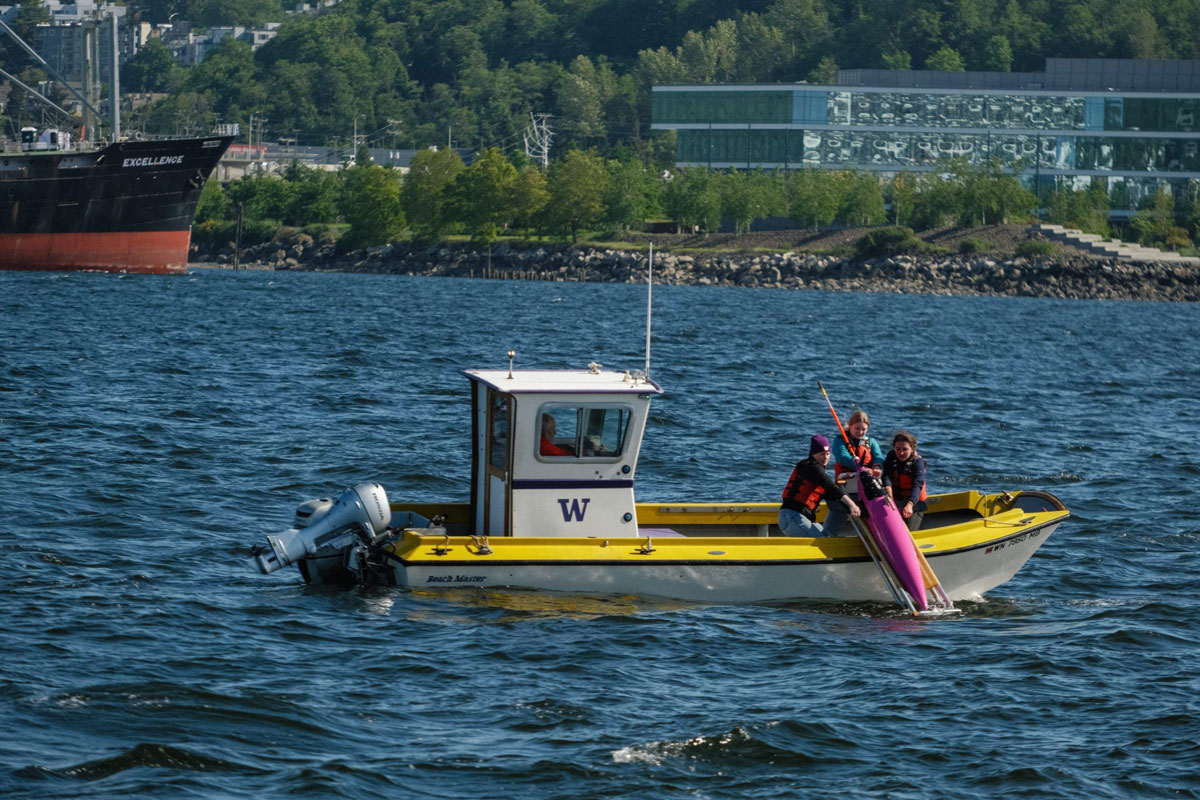

Students recover a glider during a recent deployment in Elliott Bay, Seattle.

Last fall, Kohlman saw an opportunity to join a research cruise on the R/V Sikuliaq and deploy the Pigeon in unknown terrain. The research team was investigating ocean mixing beneath tropical instability waves in the equatorial Pacific. The glider’s mission would be to travel autonomously for nine months and over 1,300 miles, diving and surfacing to gather high-resolution measurements of oxygen, salinity, temperature and turbidity while moving on a path toward Hawaii. The data would yield information of how the instability waves influence ocean mixing, air-sea interactions, biological productivity and even global climate patterns.

Once Pigeon launched, the team coordinated with other instruments deployed by the UW’s Applied Physics Laboratory and the NOAA Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory’s Ocean Climate Stations group.

Over the next few months, the students piloted the glider remotely from Seattle, monitoring its path and performance. Everything went smoothly at first. But as spring arrived, Pigeon began to falter. By the end of May, its battery was depleted. Thanks to a separate battery, the glider was still transmitting its location. The team members realized they would lose their glider to the Pacific depths—unless they found help.

That’s when Airola made the calls. And the Van Tols from British Columbia answered.

The family of four was on the last leg of their year at sea, sailing from French Polynesia to Hawaii before heading home to the Pacific Northwest. After hearing about the glider on a messaging platform, the family decided to add a few days—and more than a few miles—to their trip. Even with its location pinging, finding the glider in the vast ocean wasn’t easy. But with two extra passengers on deck and students coaching them over the phone, the Van Tols spotted the bright pink glider and brought the 120-pound instrument on board without damaging its sensors.

Digory Van Tol on board the sailboat Oatmeal Savage, soon after the glider was rescued. Photo courtesy of the Van Tol family.

It turns out the students had named it well: Like its avian namesake, Pigeon found a way home.

A few days later, Kohlman and Paige McKay, an undergraduate in oceanography, boarded a plane to meet the family in Hilo, Hawaii. When they picked up the glider, they discovered half of Pigeon’s rudder had broken, which explained why its speed and path had become erratic.

“It was an amazing feeling when Pigeon was deployed, and even better when she came up from her first deep dive,” says Ellie Brosius, ’25, the project’s chief engineer and undergraduate in electrical engineering at the time. “However, nothing compares to seeing Pigeon get rescued.”

When Pigeon finally returned home in early June, the students buckled down to analyze the trove of data it had collected. The information had already supported two student-led research projects presented at the UW Undergraduate Research Symposium in May. And there are plans for peer-reviewed publications ahead.

When Pigeon finally returned home in early June, the students buckled down to analyze the trove of data it had collected. The information had already supported two student-led research projects presented at the UW Undergraduate Research Symposium in May. And there are plans for peer-reviewed publications ahead.

“This type of hands-on experience is exactly what employers in ocean technology are looking for,” says UW research scientist and adviser Rick Rupan. “By the time these students graduate, they have already managed real missions and handled real data.”

The Student Seaglider Center, which is housed on Portage Bay in the College of the Environment’s School of Oceanography, now has nearly 30 members from fields as varied as engineering, microbiology, oceanography, business and the social sciences. They will continue to run local missions in Puget Sound and plan new long-distance expeditions—turning themselves into ocean technologists before they even receive their diplomas.

In the end, Pigeon’s adventure brought back much more than data for the students. For Airola, the team’s chief business officer, the mission was a lesson in collaboration, creativity and persistence.

“My experience in the Student Seaglider Center has been one of the most instrumental parts of my time at the UW,” she says. “Watching Pigeon return after everything we went through was incredible. It proved what’s possible when students take ownership of their science.”

And somewhere in a Seattle lab, Pigeon—its paint scratched, its rudder repaired—awaits its next dive beneath the waves.

Lead photo courtesy of the Student Seaglider Center. You can support the future of ocean science by donating to the Student Seaglider Center.