African-American alumni share the good and bad of their UW experience

There is no way to tell who was the first African-American student at the UW, the first to graduate, or what it was like for black students to go to college here in the early part of the 20th century.

True, we do know that Hamilton Greene, a law student from Seattle, was the first black football player and a member of the 1924 Rose Bowl team. But prior to those years, the history of African-American students at the UW has faded away, perhaps never to be found. To preserve the memories of other African-American students in living color, and to give all readers an impression of the black experience at the UW, we interviewed black alumni who went here during the ’30s, ’40s, ’50s, ’60s, ’70s and ’80s.

Some of what they said didn’t surprise us. Sandra Kirk Roston, ’66, ’70, saw her first roommate move out after one quarter. Her roommate’s parents didn’t want their daughter rooming with a black person. Larry Gossett, ’71, a campus activist now serving on the King County Council, says at the beginning, “We were invisible.”

On the positive side, most black graduates told us they would send their own children to the University. Many cited encouragement from their professors as a key to continuing in school. Several returned for graduate school, and some of them later came back to their alma mater to teach, work or even become a regent.

We spoke with about two dozen alumni, faculty and staff. What follows are the stories of six alumni from different walks of life whose experiences—good and bad—span six decades:

Maxine Haynes

Maxine Haynes, B.A. Sociology, 1941. Now a retired clinical nurse and nurse educator.

From the time she was a little girl growing up in Seattle in the early 1920s, Maxine Haynes wanted to be a nurse. Though her family was poor because of the Great Depression, Haynes and her two sisters were destined to attend college.

“My mother always said, When you go to college,’” she recalls. “It was embedded in our minds.” The Depression made life a constant economic struggle, but Haynes isn’t bitter. “When I think back on those times in the ’30s, I think they were some of the happiest times of my life,” Haynes recalls. “I knew I was without and I just did without.”

Economics made her decision to enroll at the UW in 1936. It was close and it had low tuition. To cover school costs, Haynes’ mother made a special arrangement with the book store to get used textbooks for Haynes and her sisters. They also took advantage of a revolving loan fund the University had. Students borrowed their tuition fee at the beginning of the quarter, then worked to pay it off. At the beginning of the next quarter, they’d borrow it back again.

There were no more than 20 black students in the late ’30s. An avid swimmer now, Haynes recalls dropping a swimming class because “no one liked us,” she says. “It was as if they had never seen black people before. They didn’t like me swimming in the pool. I felt so isolated and ignored. The teachers always helped the white students, but didn’t pay any attention to me while I was thrashing back and forth with no help.”

While Haynes felt isolated much of the time, often studying by herself and without much advising help, she does recall several successful experiences in physiology and anatomy classes. “We worked as a team dissecting a human body,” she says. “There was a lot of give and take, and a lot of class participation in the labs. The teachers went out of their way and spent extra time helping and were very friendly. I didn’t have any feeling of rejection or inferiority.”

There were even field trips. “In anthropology, we went to an Indian reservation for a potlatch celebration. I drove and took a load of students in my dad’s car to see the ceremonial dances and rituals. That was particularly fun and helpful.”

Three years into her pre-nursing program, she applied to the UW nursing school. “We are not taking colored girls,” she was told. Instead, she was given a list of 19 schools that did take “colored girls.”

“The reception I got from the UW nursing school was very, very cold,” Haynes recalls. “Unfortunately, that atmosphere was very prevalent.”

She changed her major to sociology, thanks to the guidance of Robert W. O’Brien, a sociologist and UW instructor and adviser from 1938 to 1952. “He was just an outstanding person and had a particular interest in black students,” Haynes recalls. “He was very helpful. He would have students out to his home, and he would come to our homes.”

Haynes went on to receive her bachelor’s degree in 1941, and felt “far better prepared to deal with nursing school,” she says. “It provided me with maturity.”

She attended the Lincoln School of Nursing in New York, and later got a master’s from UCLA. During her career, she worked as a clinical nurse and then as a professor. Her first appointment, in fact, was as an assistant professor at the UW School of Nursing in 1971. How did it feel to be back at the school that snubbed her years earlier? “A lot of the people who treated me poorly were gone by then,” she says. “My experiences back in the School of Nursing were OK, but there was still some racism.” She left in 1976 for Seattle Pacific University, where she remained until here retirement in 1981.

Haynes and her sisters consider themselves quite fortunate. While some black students attended the UW in the ’30s, few graduated.

Though she faced blatant discrimination, she is not bitter. “I wasn’t soured by what happened to me,” she says. “I talk to people all the time about my experiences, and tell them they can’t be bitter. You have to pass over it, and go on. I have seen too many African-American people fall into the trap of blaming the white man. It isn’t productive to hold on to it.”

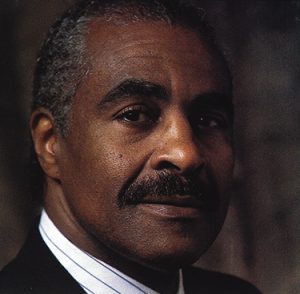

Charles Mitchell

Charles Mitchell,

B.A. History and Education, 1965. Now President, Seattle Central Community College.

Charles Mitchell was sitting in his sprawling office on the fourth floor of Seattle Central Community College, telling one of his favorite stories. As a freshman at the UW, he didn’t do well on his first history test. He knew the material; he just didn’t know how to write an essay. It was quite a shock for Mitchell, a highly recruited running back out of Garfield High School who was a better-than-average student in high school. “A TA really took an interest in me and helped me,” Mitchell says. “He showed me how to prepare an outline, and how to study and organize my thoughts. I never got below a B after that.”

When he speaks to students at the 10,000-student campus in Capitol Hill, he tells that story as often as he can. “That TA made a difference in my life,” he says. “And I want students to know that teachers care and can make a difference.”

Mitchell chose the UW because he wanted to stay close to home. He and his family came to Seattle when he was 5, and his family had lived in the Central District ever since. His home was always filled with people, it seemed. A lot of black UW athletes, especially those from California and Texas, stayed at his house on 20th Avenue between Union and Pine streets.

“Since there was no real organization for blacks, no fraternities or sororities, we did our socializing outside of school,” Mitchell says. “Everyone came to my house.”

On campus, Mitchell studied alone, as did many African-American students. But he soon started to study with white friends at a fraternity, and it paid big dividends. “I am a better learner when I work with others,” he says. “I would also study with my teammates.”

As far as being the only black student in many classes, Mitchell says, “I had very high self-esteem, and I wasn’t intimidated by it.” Still, he found himself a little lost at times because there was “no one to show you the ropes,” he says.

“You had to learn on your own. I think that was a problem a lot of black students had. A big institution like this was very foreign to us. And you didn’t want to ask a whole lot of questions because you didn’t want to be looked upon as the dumb one.”

When Mitchell encountered a speech teacher who was particularly disparaging toward black students and athletes, he considered it a challenge. “This instructor told the class he had never given an athlete more than a C, or a black more than a D,” Mitchell recalls. “I took it that something was wrong with him, not me.”

Mitchell played football at the UW from 1960 to 1962 and went to two Rose Bowls. He was the Huskies’ leading rusher in 1960 and played five years in pro football. During his time as a Husky, there were only a handful of black players on the team.

Mitchell got plenty of guidance from his parents, and from a cousin who attended WSU, the first in the family to graduate from college. “That was incredibly valuable to me,” he says. “I wasn’t alone.”

Mitchell, whose daughter attended WSU, has a son at Seattle Central who wants to attend a black college. “There are some advantages to a black institution, where a black student can get more of a real, complete college life,” he says.

“I am for education, period. It doesn’t matter where, as long as you get an education. It is also important to have the support of family and friends and not feel alone. I had that, and it made a difference.”

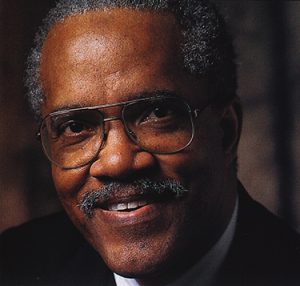

Robert Flennaugh

Robert Flennaugh, D.D.S., 1964. Now a Seattle dentist.

Robert Flennaugh sat in the office of the dean of arts and sciences in the fall of 1960, discussing his academic progress. A pre-dental student, the 23-year-old son of a farmworker had come to the UW after spending two years at the University of Alaska. The UW appealed to him because it had a dental school, the closest one to his Fairbanks home.

At the time, the UW was trying to recruit minority students for the dental school. When the dean saw Flennaugh’s academic records, he said to himself. “We have one I think can make it.” There was reason for his joy: The only black dental student prior to Flennaugh didn’t graduate.

Flennaugh was in the right place. Born in California, Flennaugh and his family moved to Alaska when he was 15. At Fairbanks High School, he was elected president of the senior class, something that gave him great confidence in his leadership abilities. “I knew I could do what I set my mind to,” he says.

So he set his mind to dental school. Though he was the only black student in his three years of pre-dental studies and his two years of dental school, he found he was treated very well. “I remember getting a low grade on a test, and I got calls from lots of professors,” Flennaugh says. “Everyone encouraged me to stick with it.”

The oldest of six children, Flennaugh says his biggest worry during school was money. His parents divorced while he was in college. He needed loans and worked all the time. He toiled in Terry-Lander during school, washing dishes and waxing floors during spring break, and took summer construction jobs in Alaska.

Flennaugh was a trail blazer, but didn’t pay much attention to that. “I was focused on getting my education,” he says. “Sure, I had no role models. I had never seen a black dentist. But the lack of role models didn’t concern me. The lack of black students did, though. I know there was racism, but none of it was aimed at me. Everyone I dealt with at the school was helpful and friendly. There was never any tension in the dental school.”

In 1964, Flennaugh became the first black student to graduate from the UW School of Dentistry, and after graduation, opened his First Hill private practice. Four years later, he joined the UW dental faculty. He later became the first African-American appointed to the UW Board of Regents, where he served from 1970-1976.

His close ties continue. Flennaugh sent both his sons to the UW (one is an aeronautical engineer, the other a lawyer), and he continues to help the dental school recruit more minority students. “We do need to reach out more to attract students,” he says.

Sandra Kirk Roston

Sandra Kirk Roston, B.A., Health Education, 1966; M.S.W., 1970. Now a counselor at Shoreline Community College.

There was talk that Sandra Kirk Roston would not be allowed to attend Enumclaw Junior High School in 1954 because she was black. Her mother spent a lot of time lobbying the principal on her behalf. That same year, as the Supreme Court made its famous Brown v. Board of Education decision banning school segregation, she got to go.

Hers was the only black family in the rural community of Black Diamond, and she and her two younger brothers were the only black students at their elementary, junior and senior high schools. “That made the transition to the UW less hectic for me,” says Roston.

What made the transition even smoother was other African Americans. Before she arrived at the UW, she had a nucleaus of friends in Seattle through the Rhinestone Club, an African-American woman’s club, and at Seattle’s traditionally black high schools, Garfield and Franklin.

Roston was a strong student who loved school, thanks in large part to her parents, who knew the value of an education. Her father, a Boeing riveter with a ninth grade education, and her mother, a community organizer with a high school degree, always encouraged her.

At the UW, she admits to feeling isolated. “I didn’t have any African-American classmates until I was a junior or senior,” she says. “The first time I had a professor of color was in graduate school.” And after just one quarter, her roommate left because Roston was black, a move that didn’t really surprise her but hurt her feelings nonetheless.

In the late ’50s the UW had no Black Student Union, no Educational Opportunity Program and no organized activities for black students. “No role models, either,” she says. But she developed social networks with the other African-American students. “There were so few of us, we all knew each other,” she says. “Since there was no place or person to turn to for academic difficulty, we relied on each other.”

Roston went to school for two years, then took a break in the early ’60s when she got married and had a son. Working as a counselor at Martha Washington School in Seward Park, she was inspired by the school’s director of social services to get a master’s in social work.

Graduate school was a much better experience for Roston because there was an emphasis on black studies, and there were several African-American faculty—James Anderson, James Leigh, Ida Chambliss and Allethia Allen. “We were looking at multiculturalism, and it was the highlight of my education,” she says. “I like to think we were ahead of our time. The classes were smaller, the students more diverse, people focused on the same goal, and we worked together. Dr. Leigh even held ‘get togethers’ for African-American students. We felt a part of something.”

If she had to do it all over again, Roston says she would have liked to attend a black college if she could have afforded it. “To have role models, and people who care about you is essential,” she says. “I would send my children to the UW, but I would also consider a black college. I feel they could get nurturing that I never got.”

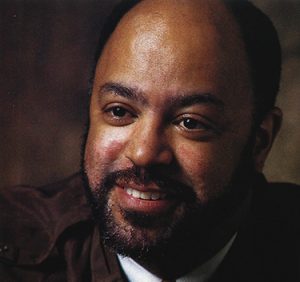

Ralph Bayard

Ralph Bayard, 8.A. 1971, M.A. 1975, Communications. Now UW Senior Associate Athletic Director.

Ralph Bayard was crossing the footbridge from Hec Edmundson Pavilion to campus when he heard the frightful news that Halloween day in 1969: He was suspended from the football team. He was accused of not being “100 percent committed” to the team. Indicative of the problems enveloping the team, Bayard learned the news from someone crossing the bridge, who had heard it over the radio. He wasn’t told in person until the next day.

“Talk about a nightmare,” says Bayard. “It was incredible.”

Actually, the nightmare—which was shared by the 12 other black players on the 1969 football team—had its roots in the athletic department well before that Halloween day. The team had its share of racial problems before Bayard arrived at the UW as a 19-year-old wide receiver from San Francisco City College. In fact, before he came, Bayard was warned about discrimination such as the lack of playing time.

Bayard wasn’t fazed. He liked Seattle, and he also knew similar problems existed just about everywhere. He also knew the UW had a black assistant coach, Carver Gayton.

But 1969 was a disaster. The team’s black players bristled at being treated unfairly, especially through “stacking,” where most were forced to play the same position—right halfback—and compete against each other for rare playing time. “It was blatantly obvious what was going on,” Bayard says. “We had some excellent talent and we were not getting the chance. It made no sense, especially because of the way we were losing.” The Huskies were at 0-6 at the end of October.

The black players wanted to meet to discuss the situation, but word somehow got back to the staff. Coach Jim Owens, afraid of a disruptive situation, assembled all 100 players on the Husky Stadium field, approached each player, and asked what their commitment to the football program was.

Unhappy with their answers, Owens suspended Bayard and three other black players—Greg Alex, Lamar Mills and Harvey Blanks. The incident caused a firestorm of outrage on campus, and gained nationwide news coverage.

“The perception was that we couldn’t give 100 percent to the program, which was totally erroneous,” says Bayard, the only starter of the four. “We were risking bodily injury six days a week playing football. For someone to think we weren’t committed was ridiculous.”

The other black players boycotted the team’s upcoming game at UCLA. Three of the four players were reinstated for the last two games of the season. In the finale against WSU, “We put all our frustration and anger into that game,” says Bayard, who scored two touchdowns in a 30-21 victory that was the Huskies’ only win all year. They finished 1-9.

The suspensions and subsequent boycott had a chilling effect the following year, Bayard’s senior season. Gayton, the black assistant coach, left. “Stacking” black players at the same position happened again, and some highly recruited black players left. This time Bayard and others kept quiet. Some of the tension from the previous year was gone, though, thanks to the Huskies’ successful season (6-4) that brought them within a victory of making the Rose Bowl. But it was a strange season.

“It felt like nothing much changed in 1970,” Bayard says. “It was almost as if 1969 never happened.”

Fortunately, the lessons of 1969 have been learned. Bayard appreciates the many changes that have been made, including the hiring of three black staff in the athletic department administration, the establishment of tutoring programs, and the hiring of coaches like Don James and Jim Lambright.

Though he was stung personally, the football team’s turmoil didn’t sour Bayard on the UW. After graduating with his B.A. in 1971, he came back to the UW for his master’s degree. “This is a great institution, and to be able to receive a degree from the UW is a great accomplishment,” says Bayard, who says he would send his two children here.

Bayard returned to the athletic department in 1993 as its chief compliance officer. “I bring a different perspective,” says Bayard, a former radio news editor and high school athletics official. “I don’t know if the students of today realize what happened before. What I went through is something you never forget.

La-Gina Simmons

La-Gina Simmons, B.A. English, 1988. Now a receptionist at WSU Cooperative Extension.

Born and raised in Tacoma, La-Gina Simmons found the UW to be a completely different world. She’d never been away from home before. She didn’t know anyone, and after unpacking her bags at Haggett Hall, she turned around and went home. But she changed her mind the next day and returned. She picked up a campus road map and a catalogue, found out where her classes were and began to feel at ease. She felt even better when she ran into people from Tacoma high schools on the UW campus.

Very close to her mother, she used to ride three buses home every weekend during her freshman year.

During her sophomore year, Simmons became close friends with a roommate from the tiny southern Washington town of Stevenson, and they “hung out” together all the time. Finally feeling comfortable in Seattle, she and her roommate did everything, from going to class to attending basketball games to finding where the best shopping spots were.

She also got very busy. A tireless worker, Simmons had a full load of classes during the day and worked from 4 p.m. to midnight five nights a week. “Between that and my boyfriend, I had no time for anything else,” she says. “I was still going home on weekends to see my mom, too.”

The second person in her family to graduate from college, Simmons always loved to read, and was encouraged by her mother. “I new I had to stick it out no matter how difficult it was,” Simmons says. “It meant a lot to me to finish and get my degree.”

Being able to finish was quite a feat, considering that during Simmons’ time at the UW, her mother was laid off and lost her house, her car and many other belongings. “My mom worked all her life,” Simmons says. “But never once during the tough times did we go on welfare or public assistance. A lot of people I went to high school with now have kids and are on welfare, and I was determined not to let myself go through the same thing. I have worked since I was 17 years old, and I always admired my mom for what she did. She was my inspiration.”

She always had lots of white friends growing up, and that was a good preparation for the UW.

“Most of my friends were white, from different towns. What was interesting was they were curious about me. They asked lots of questions about my culture and style, where I came from, about my hair, if I could teach them to dance like a black person. Even though they were racial questions, it made me feel as though they wanted to understand me. I liked it.”

Her only negative UW experience was in a few large lecture classes, where she felt the teachers were lecturing in a way black students could not quite understand. “Once I got in smaller, upper-division classes, I felt like we were on an even playing field,” says Simmons.

She has particularly fond recollections of her relationship with her Educational Opportunity Program counselor, Tony Shedrick, with whom she met at least four times each quarter.

“There were times when I’d get down because of my class load, or if an exam didn’t go well, or if I didn’t like a class. He gave me lots of guidance, and kept me working with a positive attitude. I could always go to him and talk about school, or my family.”

Still, there are times when Simmons wishes she could have spent two years at a black college. “My time at the UW was a very good experience and a lot of fun. It is a very good school. I sure learned a lot, and I’d do it again. But now and then I kind of wish I’d had the experience of attending a black school for part of the time.”

It’s obvious she has fond feelings for the years she spent at the UW. “I always look at my degree, and feel proud,” she says, beaming. She’s not afraid to show that pride where she works, even though the sign on the door mentions WSU. “I even brought it into the office to show everyone.”