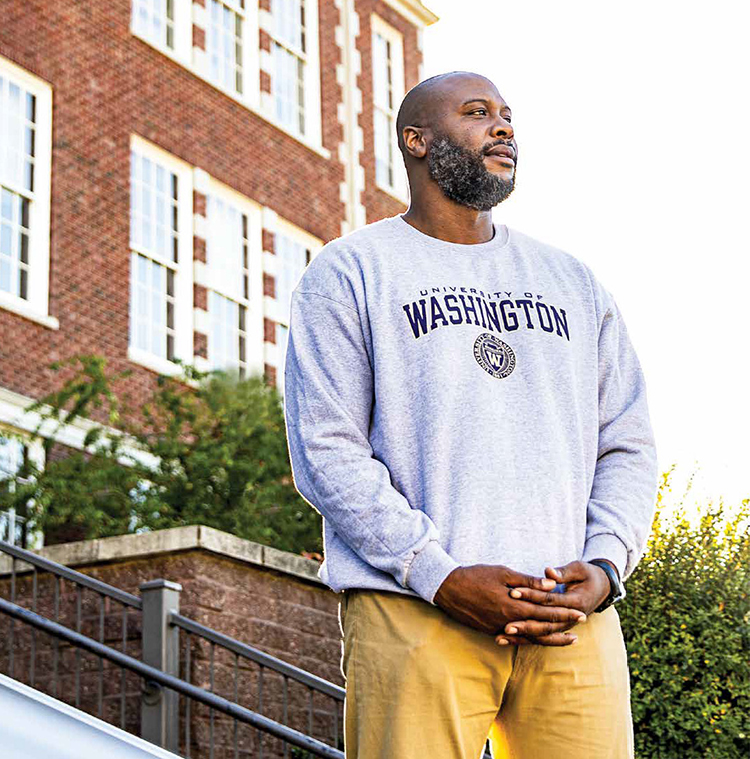

After basketball, Anthony Washington stands tall as a teacher

Anthony Washington teaches special education at Garfield High School. (Photo by Dennis Wise)

As a student at Garfield High School, Anthony Washington would walk by a special education classroom and sometimes see friends who’d been sent there for being disruptive.

“‘Hold up!’” Washington remembers thinking, his deep voice rising an octave. “‘Why is so-and-so in there?’”

Special education, implemented properly, can be transformative. It provides critical support for students with disabilities, helping them engage and succeed in school and beyond. But what Washington was seeing was different—and in his experience, it would become an alarming pattern, especially for young men of color.

Though his friends may have acted out in class, the root causes of their behavior—trauma, violence, poverty—weren’t being addressed. Instead, the special education classroom was used to keep them from distracting others in general education classes. And in missing those classes, his friends were falling further behind. It was unfair both to Washington’s friends and to the students who did benefit from special education.

From the basketball court to the classroom

But back then, Washington was focused on basketball, not school. His junior and senior years, he played on a Garfield team brimming with talent—including future Huskies Brandon Roy, Will Conroy and Tre Simmons—and a basketball scholarship brought Washington to the UW in 2002. But after two years fraught with injury and frustration, he transferred to Portland State University and then left for a decade-long professional basketball career abroad.

With stints in Germany, Qatar and the Dominican Republic, Washington says, “I kept thinking I was about to make it to the NBA.” But eventually, repeated injuries forced him to face a different reality.

He took stock of his options: “I decided to hold myself accountable. My mom had gone back to school. My grandparents were educators. Why did I feel like basketball was the only route I could take? I was like, ‘Man. I want to teach.’”

Washington hung up his sneakers in 2015 and reenrolled in the UW to become a teacher. This time, he was focused.

“It was all about not letting an opportunity fade,” he says of his second chance at a degree. “I pursued it wholeheartedly.”

Washington’s confidence grew. He made the dean’s list. And in 2016, he earned his bachelor’s in American ethnic studies and landed a job as a substitute special education instructional assistant at a Seattle-area middle school.

Changing the narrative

On his first day, Washington took in the classroom. “It was me and eight Black boys in a room. I didn’t have any instructions. I wasn’t told what to do with them. I started to realize: ‘I’m 6’10”, I’m 270 pounds,’” he recalls. “‘I think I’m just supposed to control these kids.’”

But he didn’t want to control them. He wanted to teach them.

The job became permanent, and Washington encountered a familiar, frustrating theme: the misuse of the special education classroom, and its connection to the criminal justice system for a disproportionate number of young Black men.

He remembered the fate of several of his high school friends: Sent to special education for behavioral issues without help for the underlying causes, they were considered problem students and more likely to face disciplinary actions like suspension. As they watched their teachers’ confidence in them wane, they lost confidence in themselves. School wasn’t serving them, and they eventually stopped attending; some got involved with gangs or drugs, and some were now in prison. Once they’d been labeled disruptive or difficult, it was as if his friends—and their teachers—were locked into that narrative.

Washington worried that some of his middle school students were headed toward a similar future: “When I would get called to gen-ed classrooms my students were in, it was because teachers wanted me to carry them out. It wasn’t like, ‘Hey, I need you to have a conversation with this guy.’ It was ‘I need him out of my room.’”

Washington’s goal came into focus: He wanted to be a mentor and advocate, giving students the empathy and accountability that seemed lacking. He decided to become a full-fledged special ed teacher. And that meant returning to the UW once more.

A clean slate

In 2017, Washington enrolled in the master’s program in special education at the UW College of Education. His second year, he was selected for a graduate-student teaching position at the Experimental Education Unit (EEU) at the UW’s Haring Center for Inclusive Education. It was a game-changer, providing both financial assistance and teaching experience.

At the EEU, children with and without disabilities learn alongside one another. “All the kids there are so curious,” says Washington with a broad smile. “They’re interested in everything—they’re a clean slate. This is probably what my middle schoolers used to act like. It reminded me that their curiosity is still there. It helped me stand tall on that.”

Life lessons

Washington is now in his second year as a special education teacher at Garfield High. His connection to the Garfield community gives him a strong stake in his students’ growth, and his UW and EEU training helps him create an inclusive environment where his special education students thrive—and helps him advocate for each student to be in the right learning environment for them.

“If you’re not able to take certain classes because you’re kicked out all the time, you’re not just hurt on a daily basis,” Washington says. “You’re hurt in the long run.”

He adds, “I’m big on accountability, because that’s what my students need. But I’ve got to be compassionate.”

Some of his students come to school as a safe haven: “Where they can rest. Where they can eat. Where they can hear from a positive Black dude. Most of the adults in this building couldn’t deal with some of the stuff my students are dealing with.”

Sometimes Washington shares lessons from his own life, speaking frankly of his regrets about leaving the UW during his undergrad years. In describing how he ultimately took responsibility for his future, he hopes to be a role model.

Washington is grateful for the opportunities he’s had. “The UW and the EEU— and the scholarship funding—set me up to reach these kids. To give kids who got written off a chance to get their life together. Maybe even go to college.”