Alumni cruise through Russia has a view to a coup

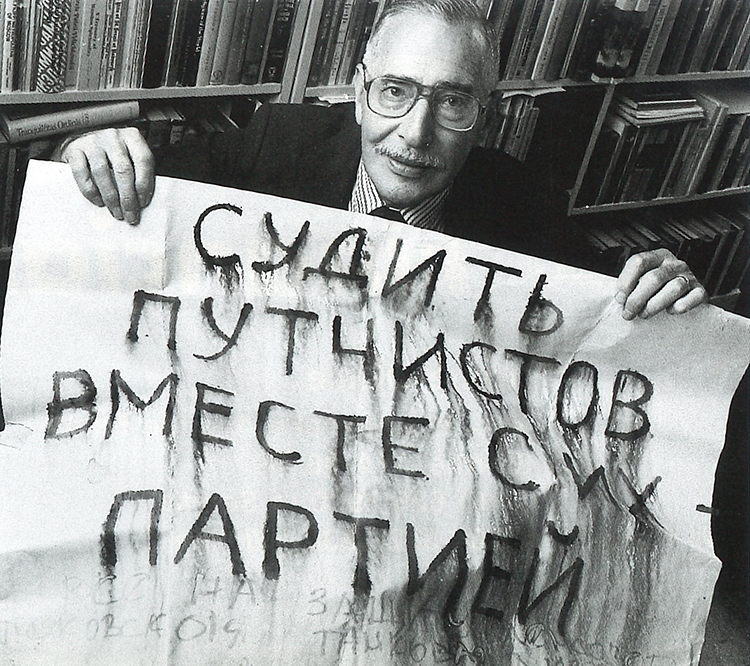

Professor Donald Treadgold holds a banner from a demonstration protesting the coup against Mikhail Gorbachev. It reads, “Bring to Trial the Leaders of the Putsch and Their Party.” Photo by Karen Orders.

Floating on a Russian lake on their way to St. Petersburg, four American professors were leading a panel discussion on “Will Russia Survive Till 1994?” As hosts of a late-August alumni cruise of the U.S.S.R., the four had just concluded that the tide of reform was not about to ebb.

Yet at that very moment the Soviet ship of state was being hijacked by hard-line Communists. It was the morning of Aug. 19, 1991, and the Second Russian Revolution was about to begin. “I remember summing it up by saying something like, ‘So we can all be glad that things have proceeded as they have … ‘ when the Russian tour director came in and announced that Gorbachev was ill and had temporarily resigned and that Vice President Gennady Yanayev, who was an ally of Yeltsin, had taken over,” recalls UW International Studies Professor Donald Treadgold, one of the tour hosts.

“We knew that something very serious had happened,” he says. “We also knew that the report had three errors. We doubted that Gorbachev was ill or that he resigned, and we knew that Yanayev was not an ally of Yeltsin.”

Betsy Thompson Senechal, ’41, was in the audience when the announcement came. She and her husband, Col. John Senechal, were taking their first tour of the Soviet Union on this UW Alumni Association-sponsored excursion. “We weren’t unduly excited,” she recalls. “We felt if they didn’t close the airports, we could get out of there.”

The tour directors insisted on business as usual, and a scheduled visit to historic Valaam Island took up most of the day. That night, while the passengers slept, the ship sailed toward St. Petersburg. For some, it was an uncertain sleep. The Red Army was supposed to enter St. Petersburg Tuesday morning in support of the coup. St. Petersburg Mayor Anatoly Sobchak, an ally of Boris Yeltsin, had called for a mass demonstration in the main square before the Winter Palace, birthplace of the first Russian Revolution.

The uncertainty was reflected in Tuesday’s agenda sheet. Normally packed with excursions, it just listed the time for breakfast, with the rest of the day blank.

Yet after breakfast, the “Cruise the Passage of Peter the Great” tour went on as planned. Tour members boarded buses to see an old fortress and a cathedral.

“On our way back from the cathedral, we drove around the edge of the demonstration. There were easily 200,000 people there in the square,” Treadgold recalls. The city came to a “complete standstill.”

“I wasn’t scared,” says Senechal of the sight. “We felt that this was a wonderful sign. We were glad that they were doing it. I probably should have been more excited than I was.”

A Red Army soldier sites on a tank sporting red carnations.

One Russian tour guide left the group to attend the demonstration and came back with a gift for Professor Treadgold. It was a hand-painted banner that read “Bring to Trial the Leaders of the Putsch and Their Party.”

A vacationing journalist on the tour also went to the demonstration. “When he came back to the ship, he told us how Sobchak gave his speech, and that the army had promised not to occupy St. Petersburg,” Senechal says. “After the demonstration, he saw people throwing cigarettes and flowers to the soldiers. It was a fairly moving moment.”

Treadgold’s first inkling that the coup might fail came when the army refused to occupy St. Petersburg. Like the rest of the world, he waited Tuesday night for news from Moscow. Would the tanks crush Yeltsin’s standoff at the Russian Parliament?

“The first time we began to be reasonably confident the coup was finished was on Wednesday, when we heard that (Defense Minister Dmitry) Yazov had killed himself. Well, it turned out to be (Interior Minister Boris) Puga rather than Yazov, but we knew that something had gone wrong.”

Like the captive Mikhail Gorbachev, Treadgold’s major source of information was the BBC, Voice of America and other shortwave stations. Rumors started filling the airwaves. The coup leaders were on a plane to Central Asia. No, they were headed to the Crimea to plead with Gorbachev. Treadgold bypassed the group tour of the Hermitage Museum—which went on as scheduled amid the unrest—to wait out the crisis.

Senechal took the tour. Remarkably, the museum was crowded, as was the circus her group had seen the night before. “The streets were filled with people, just like nothing had happened. People went about their business and went to the circus and brought their kids with them.”

Looking back, she says the whole tour was “amazing. They had 270 people to take care of. They did a marvelous job.” Because everything went so smoothly, she says, people were less concerned than they otherwise might have been. “We felt very secure with them.”

Just at the collapse of the coup, the tour group took their scheduled flight to Berlin for the last days of the trip. “It was very hard to find a HeraldTribune,” Senechal says of the international newspaper. Treadgold remembers sitting in his Berlin hotel room and watching the post-coup events unfold on CNN.

Of those 48 hours, when it looked like the coup might succeed, Treadgold remembers one striking point. “From the very first, all of the Russians we talked to, on and off the boat, made clear their opposition to the coup and their support of Yeltsin. It was not at all what we would have expected five or six years ago.”

Larisa, Senechal’s tour guide, gave a spirited talk to her charges. “She told us her husband was a radical and swore he would go out with a machine gun if the army took over,” she remembers. “She told us that people were unhappy about the food and housing, but that they didn’t want to go backwards.”

In the past, Treadgold says, he would have expected neutral statements, such as “We’re not sure. Let’s see what will happen.” That these average Russians were so outspoken pointed to “a very considerable change in attitude.”

The professor brands as “ludicrous” the contention that only a minority took part in the marches and that the majority of the Russian people “sat this one out.” “Of course not everybody took part in the revolution. People who took the risk and went out in the open may have been speaking for hundreds of thousands sitting at home.”

A bus barricade burns as anti-coup demonstrators block the exit of Soviet armored personnel carriers during confrontations in Moscow. Photo courtesy AP/ Wide World Photos.

Treadgold experienced a rare gift for a historian, witnessing first-hand turning point in his own field of a study. “It was a very important experience for me. I knew something big was happening. If the coup hadn’t been reversed, it might have lead the U.S.S.R. on the road to another the Stalin.

“Instead it landed the Russian people on a new plane of change. Of course, it was difficult to see at that point the utter collapse that would follow.”

The Soviet expert has taught at the UW since 1949 and is the author six books, including Twentieth Century Russia, now in its seventh edition. A fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and a professor of in the Jackson School of International Studies, Treadgold says he expected the Communist system to collapse one day, but thought it would occur early in the next century.

The seeds of destruction were sown with the Bolshevik Revolution and the founding of the U.S.S.R. “Communism is a system that cannot work efficiently in long run,” he declares. “As far as providing a reasonable standard of living, Communism cannot do it. That has been amply proved.”

The Communist system was doomed, he adds, since it was based on the assumption that people would work for the sake of the state. “Bolsheviks used to say, ‘If property belongs to no one, it belongs to everyone.’ Well, the truth is, ‘If property belongs to everyone, it belongs to no one,'” Treadgold explains.

“There was no responsibility, no interest in making the system productive. It was an economy based on falsehood from beginning to end.”

Despite years of indoctrination in school and total control of the media, Soviet citizens could see with their own eyes the lies presented to them. “This habit of disbelieving the press led to a widespread disbelief. People felt that everything told to them was a lie,” Treadgold says.

Those lies were confirmed by information that leaked in from the West. In the 1950s it was a trickle, but by the end of the ’80s a flood of information on Western democracy and free enterprise confirmed public opinion.

“The alienation of an increasing number of people from the system coincided with greater knowledge of the situation outside,” Treadgold says.

The UW expert adds that “some credit” must also be given to the American rearmament program. Treadgold believes that the Soviets were spending from 22 to 30 percent of their GNP on defense and faced new American initiatives such as the B-2 bomber and Star Wars. “It was a challenge that was going to be impossibly expensive to meet,” says Treadgold.

About 200,000 people fill Palace Square in St. Petersburg to protest the coup.

Since the coup, pundits, professors and politicians have composed epic catalogs of the failings of Communism. No fan of the system, upon request Treadgold can cite a short list of Soviet successes. For example, Communism could organize and build huge public works, such as the Dnieper Dam or the Soviet space center.

And he admits that the Soviet educational system was impressive. “There was a lot of rote learning, but then, we could use a little more rote learning here, couldn’t we?” He says that Russian refugees often speak highly of their cultural education. “They often told me, ‘America is uncultured. Americans don’t know anything.’”

“Their medical system is God awful,” he adds, “but the idea that everyone should have affordable medical care is a good idea, I think.” And though under Stalin historic structures—particularly churches—were destroyed, the Soviets have done a splendid job of historic preservation over the past two decades, he says.

In the long run, Treadgold is cautiously upbeat about the future of the Russian people. The nation has wealth of raw materials. It is still the world’s largest oil producer, and its space program is an example of a “high-tech” success.

Perhaps its greatest asset is the character of the Russian people, Treadgold adds. “They have enormous energies and an enormous ability to endure hardship. Now let us hope their strengths can be turned to more positive efforts.”

Treadgold is an advocate of food and medical aid during the coming winter—provided Western nations ensure that it gets to the right people. However, he opposes a sudden “Marshall Plan” that would pump hundreds of millions of dollars into the current economy.

“The Marshall Plan worked in post-war Western Europe because there was an institutional structure and experience under capitalism. It enabled them to rescue economies based on free enterprise.

“What we have in the Soviet Union is not the same at all. I find the Marshall Plan analogy not helpful and, in fact, confusing. It is based on the illusion that money will solve all the problems in the world.

“You just can’t do that to an economy in the shape of that of the Soviet Union. You might as well stand in front of a toilet and flush the currency down.”

Massive economic aid should only be given when there is some structural movement. Treadgold would like to see extensive privatization of industry and collective farms, financial reform and currency reform. “It is going to be a slow, difficult, very painful process. And it is going to take a long time.”