At research center, patients take on risk for the sake of a cure

From bone marrow transplants to cancer vaccines, patients in the clinical research center opt for experiments that could save lives, maybe even their own.

As 53-year-old Russ Ewan sits in the exam room to have his blood drawn, he keeps the conversation light, tempering it with a few jokes, or comments about the weather and his drive from Spokane.

He smiles as he pockets the $15 he gets each time he comes to the UW’s Clinical Research Center (CRC). “A patient getting paid by a doctor! You don’t see that very often, do you?” he quips.

In the waiting room, the atmosphere is similarly relaxed. Patients sit quietly, reading magazines and staring out the seventh floor window, perhaps tuning in to the familiar hush of the hospital. RNs pop in and out, calling their names and leading them down the hall.

On the surface there is little to distinguish the CRC from any other clinic in the medical center.

Yet here, in seven rooms on the seventh floor in the south wing of the University of Washington Medical Center, is where patients are receiving some of the world’s newest potential treatments for their diseases. Ewan is part of an experiment to combat hepatitis C.

The CRC has been a source of hope since it opened in 1960. That year, Dr. E. Donnall Thomas performed the world’s first bone marrow transplant that resulted in the long-term survival of the patient. Thomas won the 1990 Nobel Prize for medicine for his pioneering bone marrow work at the UW and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

On March 9, 1960, a team of UW physicians and engineers led by Dr. Belding H. Scribner implanted a Teflon tube in a man dying of chronic kidney failure, paving the way for long-term kidney dialysis. The patient lived another 11 years; long-term kidney dialysis has saved hundreds of thousands of lives since. As soon as the center opened, Scribner used it as a testing ground.

Since its inception, the center has seen more than 900 major research projects involving approximately 2,500 investigators from a variety of disciplines at the UW. About 5,000 patients volunteer for experiments each year.

Much of this research involves new drugs or new ways to deliver existing drugs. To ensure a new drug or treatment is safe and effective, the federal government breaks clinical trials into three phases. Phase I trials try to determine the maximum safe dose of an experimental drug or treatment; phase II trials are designed to confirm that safety and effectiveness.

Phase III trials attempt to prove the safety and effectiveness of the new treatment by comparing it to a conventional one. These trials, which the U.S. Food and Drug Administration uses to determine whether to approve a new drug, involve hundreds of patients at research centers across the country, and last for months, sometimes years.

It takes years for a drug to make it from a phase I trial to FDA approval. For example, doctors had success treating advanced kidney cancer with Interleukin-2 approximately seven years before the drug was approved by the FDA.

Connie Castle

Connie Castle, 50, of Colbert, Wash., was diagnosed with a very aggressive type of breast cancer in 1991. She underwent surgery, and was in remission until 1994, when an exam revealed that the cancer had reappeared in another part of her body with renewed hostility.

Connie Castle, 50, of Colbert, Wash., was diagnosed with a very aggressive type of breast cancer in 1991. She underwent surgery, and was in remission until 1994, when an exam revealed that the cancer had reappeared in another part of her body with renewed hostility.

“They found it had almost eaten entirely through my upper left femur,” she says. A year of chemotherapy followed, but Castle eventually had to have her hip replaced.

“You never really feel safe after you’ve had a recurrence. If you’ve had one, you usually have another one down the line,” she says.

But Castle didn’t have to sit and wait; she’s received a new cancer vaccine in a CRC phase I trial led by Medicine Professor Mary L. Disis, who is also an affiliate investigator at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

The vaccine, developed by Disis and her colleagues at the UW over the last seven years, is designed to stimulate a patient’s immune response against certain peptides. These compounds accelerate the growth of cancer cells, leading to aggressive progression of the disease.

Sixty women will participate in the trial. So far, 12 have received the vaccine; Castle, a graduate student in clinical psychology, was the first. “Since I’m the first human to do this, we don’t know if these numbers will stay up,” she says.

Castle’s “numbers” are the cancer-fighting lymphocytes her immune system is mounting in response to the vaccine. “I feel honored to be the first person in the trial,” she says.

During the trial, doctors want to find the highest dose that can be given without adverse reactions. Castle, having received her last vaccination in January, is being monitored for side effects. So far, so good.

Castle recalls sitting in an exam room at the CRC after receiving the first of six injections. Doctors were monitoring her closely for side effects. She slipped on Mickey Mouse ears when the RN left the room. When the nurse returned, she declared, “I’m having side effects… I’ve been craving cheese.”

“Humor is a part of healing,” she says. But Castle goes through a lot of worry too. The abnormal peptides that quickened the growth of her cancer are expressed by her own genes. “I’m vaccinated against something my own body makes,” she says.

Castle had to postpone work on a master’s degree in clinical psychology throughout much of her battle with cancer. Recently, she completed the degree and defended her research for the first time. Her thesis concerns biologic, psychological and social variables that contribute to breast cancer. After all, she’s an expert.

Knowing that her participation in the trial, no matter what happens, will have some future benefit for people with the same disease is important for Castle. “It helps give a meaning to the illness,” she says.

Christy Nelson

Helping others motivates most patients participating in clinical trials, such as 39-year-old Christy Nelson of Arlington, Wash., who was diagnosed with a brain tumor in 1995.

Helping others motivates most patients participating in clinical trials, such as 39-year-old Christy Nelson of Arlington, Wash., who was diagnosed with a brain tumor in 1995.

“I don’t know if they expected me to be alive this long,” says Nelson, one of nine local women currently in a phase II clinical trial to determine whether temozolomide, an experimental anti-tumor drug, works.

Nelson says if it wasn’t for the fact that she is contributing to science, she probably wouldn’t have agreed to be in the trial. Not that it’s been a bad experience, at least until lately, due to steroids she takes to reduce swelling and fluids around her brain. “The steroids keep me crying, screaming and complaining. I can’t get to sleep,” she says.

The phase II trial, led by Medicine and Pathology Professor Alexander Spence, is also going on at approximately 19 other clinical sites. The trials will see if oral temozolomide works against malignant “gliomas,” rapidly growing brain tumors.

Nelson began taking the drug at the beginning of March. At the end of her treatment, doctors will take an MRI to see if the treatment stopped or slowed down the growth of the tumor.

“If it’s improved, or the same, I can take it for up to another year,” she says. “If not, they’ll stop, and I’ll soon be gone.”

Nelson, who worked for the Bon Marché in Everett for 12 years, recalls not feeling well when she left her house one day late in 1995 to visit her mother in a Stanwood nursing home. The drive, one which she’d done hundreds of times over the past seven years, was a blur.

At the nursing home, Nelson wasn’t able to get a sentence out, and she remembers trying to tell someone that she needed to lie down. Later, at a hospital in Mt. Vernon, doctors discovered she’d had a stroke associated with a brain tumor.

The day after Christmas, 1995, she underwent surgery at the UW Medical Center. The doctors removed part of Nelson’s brain. “Sometimes I think they took too much when I have trouble talking,” she laughs.

Following the surgery, Nelson had radiation treatment. Things were fine until last January, when she started feeling ill. An MRI revealed the tumor had grown back. She wasn’t aware of the drug trial until she was approached by the researchers involved.

“I thought, ‘Do I want to or don’t I?’ If it was miserable, I probably would have stopped, but it wasn’t,” Nelson admits.

Nelson has accepted the fact that her condition is terminal. “There’s nothing you can do. You know you don’t have a chance for sticking around for very long,” she says.

Helping someone in the future, however, allows Nelson to feel a sense of empowerment while being up against unbeatable odds. “That was my intent, to help people, maybe someone in my own family,” she says.

Russ Ewan

Russ Ewan, $15 richer and still smiling as he walks down the CRC hall toward the elevators, comments that maybe he’ll spend it on St. Patrick’s Day.

Ewan’s journey to the CRC began in 1983, when he contracted hepatitis C through a blood transfusion while undergoing double bypass heart surgery. “It was bad blood,” he says.

Seven years later, Ewan, a retired Spokane Spokesman-Review circulation manager, was diagnosed with hepatitis C after his doctor discovered his liver had deteriorated. He went to a specialist and then to a physician at Harborview Medical Center, who in turn referred him to a phase III trial at the CRC led by Medicine Professor Robert Carithers.

Approximately 1,000 patients at about 40 clinical research sites across the country are enrolled in the trial. It is a double-blind, randomized test of Intron A, the only approved treatment for hepatitis C, in combination with the investigational drug “ribavirin,” which has been approved by the FDA for research purposes only.

Being a double-blind trial, Ewan was randomly assigned to one of four treatment groups receiving either Intron A plus a “dummy” drug, or Intron A plus ribavirin. Neither the patients, physicians or study staff know what an individual patient is taking.

In order to evaluate the combination, researchers need something to compare it with. In this case, they are comparing a potential new treatment, the Intron A and ribavirin, and the conventional treatment, Intron A alone.

Patients receiving the Intron A alone are given a dummy drug as well so that on the surface, at least, the playing field is level. “I’d have to think I was getting the real one the way things are going, but I guess you never know,” Ewan says.

Ewan’s hepatitis C viral counts dropped from 2.2 million copies per milliliter prior to the study, to less than 100 copies per milliliter after 24 weeks of treatment. They are good results, but since no one knows which treatment he’s receiving, no one can say exactly why.

In the United States, approximately 600 people a year die of liver failure after getting hepatitis C. About half the people who get it never fully recover, some developing cirrhosis of the liver and liver failure.

Ewan gives himself injections of Intron A three times a week, and takes three of what is either the ribavirin or dummy pill twice a day. He visits the CRC once every four weeks.

There are side effects. Intron A causes fever, fatigue, chills, nausea, headaches and poor appetite, while ribavirin has been known to cause anemia. Ewan has escaped the anemia, but not the flu-like symptoms.

“Some days you don’t feel like getting out of bed,” he says.

Kristin Thueringer

Through the clinic entrance at Children’s Hospital and Medical Center, past a waving Mickey Mouse and up the elevator to the seventh floor, you will find the pediatrics satellite of the UW Clinical Research Center.

Through the clinic entrance at Children’s Hospital and Medical Center, past a waving Mickey Mouse and up the elevator to the seventh floor, you will find the pediatrics satellite of the UW Clinical Research Center.

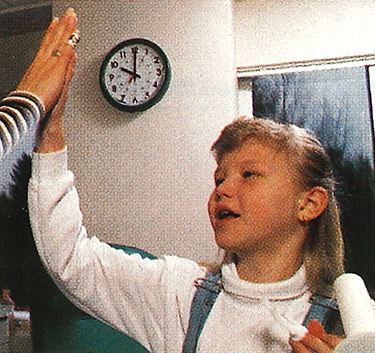

In a consultation room, you will see 9-year-old Kristin Thueringer; her mom, Carol; and her dad, Dennis. They sit comfortably, discussing the trial which, on that day, ended for them.

“It’s a shame to get a good drug and then get pulled off of it,” says Carol. There’s a chance the family can apply to the pharmaceutical company that holds the patent to get extra doses for “compassionate use.”

Kristin, who was diagnosed with cystic fibrosis at the age of 9 months, struggles with a chronic lung infection. The trial used a “nebulizer” to administer high doses of a drug often given to patients with lung infections.

The nebulizer, or inhaler device, allows the drug—tobramycin—to go straight to the area of infection, and at high enough doses to kill the bacteria. The trial was led by Cystic Fibrosis Center Director Bonnie Ramsey, associate professor of pediatrics and associate program director of the CRC.

If you talk to Kristin, she will spin out a raft of scientific and ingenuous descriptions she’s picked up from the trial. She describes the scar tissue in her lungs, the flu that put her in the hospital twice last year, and what it’s like being accessed intravenously through a port under the skin of her chest. On an X-ray, the port “looks like a lifesaver,” she says.

Participating in the trial had major benefits, and improved her daughter’s lifestyle tremendously, Carol says. It seems to have kept her out of the hospital this year.

“This was something to gain time until they come out with genetic therapy,” Dennis says.

“But we don’t know how soon that will be,” Carol adds.

Kristin is unperturbed. Her face lights up as she explains that this year at school, she plans to go out for track. She exchanges a confidential smile with her mom, and says that the 600-meter run will probably not be her event.

“I’m best at the 50-yard dash,” she beams.

Running track is nothing compared to the pain and stress of the clinical trial. The worst part was getting used to the needles, Kristin says. She didn’t like them at first. “So, I said `Okay, Kristin, you have to get over the needles. They are going to be doing this now once a month,’ ” she recalls.

Now, they don’t bother her.

Watching her daughter explain how she dealt with her fear of needles, Carol’s eyes fill with admiration and then brim.

Indeed, Kristin Thueringer is a courageous girl.

Ewan, Nelson and Castle are just three of the average 5,000 patients who visit the CRC per year. The average stay for a patient is five hours. Yet, the CRC and its satellite at Children’s Hospital and Medical Center, which opened in November, are far from the kinds of places where patients feel isolated or anonymous.

“Everyone there is so professional and so caring. You can’t be just a number,” says Castle of her experience.

Ewan, who postpones the drive back to Spokane when he visits by staying in Seattle over the weekend, says of Hepatology Research Coordinator Kersten Beyer, “She’s so upbeat, she makes me feel like I want to be a part of it.”

Nelson said the trial is playing a role in how her family is coping with her condition. “They’re at loose ends,” she says.

Participating in a clinical trial can be a way for individuals and their families to come to terms with terminal disease, according to Clinical Nurse Specialist Andrea Bakke, who works with cancer patients in phase I and II trials at Children’s. “Phase I studies can provide a little more time for people who aren’t prepared for their child to die,” she says.

Some families have to believe in beating the odds. “Once you’ve given them a shred of hope, they never let go,” Bakke adds.

With or without hope, everyone’s participation in a phase I, II, or III trial is a contribution to knowledge, Bakke says. Ultimately, that is something everyone can be proud of.

There are 74 clinical research centers across the country. At the UW alone there are 127 active projects, ranging from treatments for hypertension during pregnancy to HIV infection.

All 10 of the adult and pediatric beds at the CRC are inpatient beds, but they are used less and less at night. The idea of “inpatient” has changed substantially in this modern age of medicine, says CRC Director John Brunzell.

“We’ve shifted from long-term studies to short term as we’ve moved into modern medicine,” he says. The methods for delivering treatment, and diagnosing it, have improved so much that the average length of stay at the center is five hours. Out of the average 5,000 patients who visit per year, just 500 stay through midnight.

Every five years, the CRC renew its grant to the National Center for Research Resources. While some projects are funded wholly by private industry, the CRC receives most of its funding in from the federal government. Last year it received approximately $2.4 million for clinical trials. The federal health agency also recently awarded the center $700,000, which the UW will match, to build one of the first gene therapy labs in the nation.

UW researchers submit their proposals for clinical trials to a CRC committee made up of 12 members. The committee reviews the proposal and then passes it on to a biostatistician. For the project to be approved, and for the trial to begin, all must agree, at least, that “this is very good science,” says CRC Manager Karen Monteiro.

It’s too early to tell the fate of their experiments, or the fate of these three research subjects. But for Russ Ewan, Christy Nelson, Kristin Thueringer and Connie Castle, the clinical trials at the CRC are “good” science toward the greater good of us all.