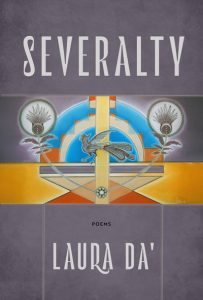

Award-winning poet Laura Da’ traces land loss, trauma and healing in her new collection, “Severalty”

In her third poetry collection, teacher and poet Laura Da’ explores Indigenous endurance in the face of erasure.

Laura Da’, whose book “Severalty” references the Dawes Severalty Act, studied creative writing at the UW and the Institute of American Indian Arts.

Laura Da’s latest poetry collection, “Severalty,” centers on the Dawes Severalty Act of 1887, a piece of federal legislation that was used to dismantle the political, cultural and territorial cohesion of tribal communities. The law authorized the division of communal reservation lands into individually owned parcels.

“It had a direct bearing on my ancestors by reducing tribal landmass into small allotments, which were then sold or stolen, and by facilitating the boarding school experiences that traumatized my grandparents and great aunts and uncles,” Da’ says.

Born in the Pacific Northwest, Da’ is an enrolled member of the Eastern Shawnee of Oklahoma. She studied at the Institute of American Indian Arts before completing her undergraduate degree in creative writing at the UW in 2001. “Tributaries,” her first book, received an American Book Award.

The historical framing of the Dawes Act underpins “Severalty’s” exploration of tension between brokenness and wholeness. In a long prose poem, “Passing the Frontier,” the poet catalogs the scope and lasting impacts of allotment in a frontier marked by dispossession: stolen land, stolen children and stolen memories that tore 90 million acres away from tribes. “Allotment broke the trail into an impassable road from ancestors to progeny,” she says.

The historical framing of the Dawes Act underpins “Severalty’s” exploration of tension between brokenness and wholeness. In a long prose poem, “Passing the Frontier,” the poet catalogs the scope and lasting impacts of allotment in a frontier marked by dispossession: stolen land, stolen children and stolen memories that tore 90 million acres away from tribes. “Allotment broke the trail into an impassable road from ancestors to progeny,” she says.

As Da’ was writing her collection, she experienced a series of personal trials, from a kidney transplant and recovery to cancer and the loss of friends and family to COVID-19. But she also “lived in happiness, looking forward to the garden, coffee in the morning.” Her healing journey helped her find a sense of integrity in rupture. “In this way, I see the title as a mirage,” Da’ says. “We are always in severalty, right down to our atoms. The state of separation must also underpin the fundamental logic of our wholeness.”

Nearly a third of the poems in “Severalty” are concerned with the body and its relationship with intergenerational trauma and its residues, which affect present-day Indigenous ecosystems and experiences. Da’ writes of hospital stays, surgeries, morbidities, autoimmune illness and the genetic severalty that results from making the body a mined landscape.

Da’s inventiveness with language and the influence of avant-garde poetry are apparent in “Cross-Stitch Primer,” a poem that describes a visual work of art and is organized alphabetically, reflects on grief embodied in stitched alphabetical primers made by firstborn daughters to mourn the loss of their mothers. This meditation on maternal knowledge and loss, endurance and memory, interacts with other poems throughout “Severalty” that touch upon Da’s perspectives as a mother.

Twelve poems are titled simply by a directional arrow. These pieces invoke a place, direction or intention both inside and outside time. “They’re like seeds that you plant and tend well, hoping that they’ll thrive to harvest and be planted again. … Some will inevitably remain underground,” Da’ says. “The metaphor of a strung arrow needing to be drawn back to move forward was on my mind when I created this series.”

Da’ studied at the Institute of American Indian Arts during a vibrant moment in Native American literature, and she was mentored by poet and translator Arthur Sze. The institute nurtured a generation of groundbreaking writers like Layli Longsoldier, Jennifer Foerster and dg nanouk okpik, contemporaries who, like Da’, confront historical erasures while excavating a sacred relationship to land, water and the more-than-human world.

“I think of my work as witnessing and reclaiming and also living through the material conditions laid down by the past,” Da’ says. “In Shawnee language, verb tenses don’t function temporally like in English. Instead, there are conditions of the known and unknown. The past and present are known. The future is unknown. This sensibility comes into this collection as pertains to witness, reclamation and documenting the lived present.”