Best of 1998: UW honors top teachers, staff, volunteers

From a professor of “dead” languages to one who explains computer languages, from the founder of a “buyer’s club” to an alumnae club serving the UW since 1909—the UW is honoring the best teachers, staff members and volunteers in an expanded awards program for 1998. Seven are UW professors chosen by a panel of faculty, students and alumni as this year’s top teachers. Two are teaching assistants named by the same panel. Three awards honor the best in public service to the University and the community; and five awards go to outstanding staff members.

Distinguished Teaching Awards

Lawrence Bliquez

When Lawrence Bliquez was entering high school, his father urged him to attend the local Jesuit school. Bliquez, noting the absence of a football team at the school, preferred another Catholic school. “But Dad,” Bliquez recalls shouting at his father, “If I go to the Jesuit school, they’ll teach me Greek and Latin and what would I ever do with that?”

When Lawrence Bliquez was entering high school, his father urged him to attend the local Jesuit school. Bliquez, noting the absence of a football team at the school, preferred another Catholic school. “But Dad,” Bliquez recalls shouting at his father, “If I go to the Jesuit school, they’ll teach me Greek and Latin and what would I ever do with that?”

Bliquez won the battle but his father won the war. It is for teaching classical languages at the UW that Bliquez is being honored with a 1998 Distinguished Teaching Award.

It was in college that he discovered the charms of the classical world—first by participating in a “Great Books” program, then as a tutor for his roommate, who was taking Greek. The roommate dropped Greek, but Bliquez eventually earned his degree in Greek. Then came graduate school, and then came teaching.

“I stunk,” is how Bliquez evaluates his teaching efforts during graduate school. He was still struggling when he got his first teaching job at San Francisco State University. But Bliquez wanted to be a good teacher, so he paid attention to student evaluations. “I could see that what I had going for me was my enthusiasm for the subject and the kind of personality students could relate to,” he says now. “I tried to build on those.”

By all accounts he’s succeeded. One student commented that he knew Bliquez had taught a particular class many times, “but instead of boring, lackluster lectures, he brings excitement and energy to every session. It appears as if he is exploring the topics with us for the first time.”

“He is incredibly attuned to his classes,” says another student. “This is a professor who can look at me and tell if I understand something.”

“There are certain parallels between what we humanists do and what clerics do,” Bliquez says. “When you teach the classics, you’re helping people to learn about themselves because you’re giving them a model to compare themselves to. The Greeks and Romans, after all, raised most of the important questions—justice, duty, citizenship, statecraft, fate, God—and they gave some answers that are still interesting, even if you don’t agree with them. These are questions I think every student should wrestle with.” —Nancy Wick, UW News and Information

Carol Leppa

Carol Leppa, who won a 1998 Distinguished Teaching Award at UW Bothell, is at least as enthusiastic about her students as they are about her.

Carol Leppa, who won a 1998 Distinguished Teaching Award at UW Bothell, is at least as enthusiastic about her students as they are about her.

“The students in this program are really special,” she says. “They bring a wealth of knowledge and experiences with them to class, and that enriches our work together.”

Most of her students are nurses who have R.N. (registered nurse) certification and are now working to complete a bachelor of science in nursing degree. Most work full time while going to school. The students’ average age is 37.

One of Leppa’s most popular classes is “Ethics and Values in Health Care Systems,” where students compare health-care systems in the United States and Great Britain, followed by an intensive 11-day program in London.

Students come back having “learned about and experienced a nationalized health service and with a clearer sense of what our own health-care system is,” Leppa says.

One student says: “The lectures we attended while in London stimulated conversations about socialized medicine, ethics and politics. I was so inspired after this trip, I decided to learn more about the way politics affects health care in our society.”

Leppa also teaches a course on “Women’s Health, Women’s Lives” and other nursing courses.

“Her sense of humor, keen intellect, clarity and commitment to students and the nursing profession have earned her our affection, respect and admiration,” another student says.

Leppa received her Ph.D. from the University of Illinois at Chicago in 1990, and came to the UW to do postdoctoral work in nursing systems with then-Nursing Dean Sue Hegyvary. She jumped at the chance to teach at UW Bothell.

“I was intrigued by the program specifically designed for R.N.s and I thought it would be exciting to be part of building something new,” she says. “In many ways it’s easier to develop an innovative project like the London course as part of a new program.”

But it’s the students who really inspire her work. “I look forward to continuing my teaching and learning with these non-traditional students,” she says. “They really make my work interesting!”—Claire Dietz, Medical Affairs News and Community Relations

June Lowenberg

The content of June Lowenberg’s courses at UW Tacoma guarantees that she faces tough teaching situations. A senior lecturer in nursing, Lowenberg teaches classes in death, grief and loss, as well as in race, class and gender.

The content of June Lowenberg’s courses at UW Tacoma guarantees that she faces tough teaching situations. A senior lecturer in nursing, Lowenberg teaches classes in death, grief and loss, as well as in race, class and gender.

“When I’ve taught courses on death and dying, students do things from preparing eulogies to interviewing chaplains,” she explains. “There are always a few people who grapple with very personal issues, death and grief issues, sometimes from long ago. Sometimes students share that they have considered suicide. I need to be open and available,” she says.

Students find Lowenberg both passionate and compassionate, a scholar excited about sharing her academic expertise, but also a human being who shows great concern for those she teaches.

“June has a unique way of integrating matters of the head with matters of the heart,” writes one graduate who nominated her for a 1998 Distinguished Teaching Award.

Lowenberg explains that students who take her classes are required to stretch themselves, and not just intellectually. “They also have to gain self-insight and sensitivity to their own fears and to those of others,” she says.

Lowenberg, who holds a Ph.D. and M.A. in sociology from the University of California, San Diego, an M.N. in pediatric nursing, a B.S. in nursing, and an R.N, says she appreciates her older students at UWT.

UWT Dean and Vice Provost Vicky Carwein, herself a nurse, praises Lowenberg for her charismatic teaching skills, as well as for her research and encouragement of lifelong learning in her students. “June has touched the lives of hundreds of students, the faculty and staff here at UWT, as well as at other universities and organizations,” says Dean Carwein.—Jamie Martin-Almy, UW Tacoma

Tracy McKenzie

When the UW history department hired Tracy McKenzie in 1988, he filled a position vacated by legendary Professor Tom Pressly, a Distinguished Teaching Award winner. At the time, a faculty member predicted McKenzie would “honor the position held by Professor Pressly.”

When the UW history department hired Tracy McKenzie in 1988, he filled a position vacated by legendary Professor Tom Pressly, a Distinguished Teaching Award winner. At the time, a faculty member predicted McKenzie would “honor the position held by Professor Pressly.”

Not only has McKenzie honored it, he has followed in Pressly’s footsteps by winning a 1998 Distinguished Teacher Award himself.

“For the last few years, undergraduate students have been telling me what a good teacher Tracy McKenzie was, and my visit to his classroom confirmed their impression,” one colleague says. “What I witnessed was a polished, lucid, and engaging explanation of how the Union began disintegrating between 1848 and 1858. His teaching surely helps to bring distinction to the history department.”

The same students who describe him as a “fabulous professor” and “charismatic” also note receiving strong criticism and low grades from McKenzie, who teaches Civil War history. (His comments on student papers can rival the papers themselves in length.) “His standards may be high, (but) no one ever complained that they were unfair or that they did not get the guidance they needed to meet those standards,” a student comments.

“I’ve always thought that the role teachers should play is to follow the old newspaper motto to ‘comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable,’ ” McKenzie says. “I don’t intend on leaving my students in a self-congratulatory mood. I want them examining and questioning their attitudes—not necessarily discarding them, but examining them.”

“Tracy takes risks as a teacher,” a colleague wrote. “He is scrupulously careful to distinguish between history and his own opinions, but at the same time he models in himself the claim that he urges upon his students: that history demands of all of us that we engage ourselves personally with it.”

“The idea is not that at age 21 [students] have all the answers,” McKenzie says, “but that they can articulate the conflicts around their world view.”—Nedra Floyd Pautler, UW News and Information

Terry Mengert

How do you teach a classroom full of medical students to cope with a patient arriving at the “ER” with heart attack symptoms? If you’re Terry Mengert, you might challenge them to a spirited game of “Myocardial Infarction Jeopardy.”

How do you teach a classroom full of medical students to cope with a patient arriving at the “ER” with heart attack symptoms? If you’re Terry Mengert, you might challenge them to a spirited game of “Myocardial Infarction Jeopardy.”

Mengert advocates learning by doing, and likens learning a medical skill to mastering a tennis stroke. “You don’t get good by reading or hearing about how to hit a backhand, you get good by doing it. The same is true of learning to be a doctor.

“In teaching medicine, we’ve often made the mistake of being too passive,” he says. “I’ve tried to make it more active, by presenting students with clinical cases, asking a lot of questions and expecting answers.”

Mengert’s creativity and compassion led to his winning a 1998 Distinguished Teaching Award. Despite having completed two UW bachelor’s degrees (zoology and forest resources), a UW medical degree, a residency in internal medicine in UW-affiliated hospitals, and 11 years as a UW emergency-room physician and faculty member, Mengert says he’s still learning.

“The questions and issues that the students and housestaff raise teach me; in fact, I think I learn more from them than they do from me,” he says.

“Terry’s teaching occurs at the bedside and in the hallway more than in a traditional lecture hall,” says Mickey Eisenberg, director of the Emergency Medicine Service at UW Medical Center. “The bulk of his teaching occurs in a unique and demanding setting: a busy emergency department. I consider him a master teacher of clinical medicine.”

“In an area of medicine that moves at a fast and even intimidating pace, he has the ability to make the emergency department a comfortable and enjoyable learning environment,” notes one of his students.

The UW award is the latest in a string of teaching awards for Mengert. He was named a role model by fourth-year medical students, received the Beeson Award voted by medical students for the best clinical teacher in the Department of Medicine, and has received the “Golden Apple” award from students in the Medex Northwest Physician Assistant Training Program in each of the last three years.—Laurie McHale, Medical Affairs News & Community Relations

Ted Pietsch

The Kuril Archipelago’s remoteness has prompted Russians to refer to it as the end of the world. Storms, volcanic eruptions, tidal waves, blistering winter winds and thick summer fogs have given the chain of 56 islands in the North Pacific a reputation as hideous and uninhabitable.

The Kuril Archipelago’s remoteness has prompted Russians to refer to it as the end of the world. Storms, volcanic eruptions, tidal waves, blistering winter winds and thick summer fogs have given the chain of 56 islands in the North Pacific a reputation as hideous and uninhabitable.

What a great place for a classroom.

Three undergraduates and three graduate students from the UW will accompany this summer’s expedition funded by the National Science Foundation and led by Ted Pietsch, professor with the School of Fisheries. The students will work alongside 25 scientists from the United States, Japan and Russia, just as students have done each of the last five years.

Whether standing before a roomful of students or by a stream of 90-degree water explaining how to net heat-loving fish called “gobies”—Pietsch’s ability to weave together research and teaching earned him a 1998 Distinguishing Teaching Award.

“Pietsch’s talks could never be construed as the presentation of a list of scientific ‘facts.’ Rather, his ability to integrate information with the history of science and scientific personalities and to emphasize science as a dynamic endeavor broadens the perspective of the topic beyond ichthyology,” wrote a fisheries graduate student.

Pietsch’s courses include “Biology of Fishes,” a basic science course he has team taught with Fisheries Professor Chris Foote for the past four years.

Foote says one reason Pietsch is such a good teacher is because he is so well prepared. “For each class, he provides for the students a complete (I mean complete!) set of notes in the library, so that they don’t have to waste time taking notes. As such, he presents more material per lecture than normal and the students learn more. ”

Pietsch also is curator of the UW fish collection. Every quarter undergraduates work with Pietsch and Collections Manager Brian Urbain. The collection focuses on fish of the Pacific Northwest and Alaska but includes specimens from around the world. A 1995 survey showed that the UW collection was the fifth most-heavily used collection in North America.

Sets of specimens are especially set aside for use by students, both those attending the UW and other colleges, as well as younger students in grades K-12.

“Ted has often voiced to me his belief that young people can be attracted to the sciences by exposing them to natural history when they are in the K-12 system,” wrote David Armstrong, professor of fisheries. “Ted has used the extensive facilities of the School of Fisheries collection as the basis for tours and lectures for school groups—young people at an age when their imaginations are attracted by fish with such a diversity of odd forms and shapes or those with strange lifestyles, and by the mix of science and adventure behind collections and museums.”—Sandra Hines, UW News and Information

Anita Ramasastry

In her first year on the faculty of the UW law school, Anita Ramasastry was named Teacher of the Year by the Student Bar Association. Now in her second year, she’s topped that with a 1998 Distinguished Teaching Award. How did one so young hit the heights so fast?

In her first year on the faculty of the UW law school, Anita Ramasastry was named Teacher of the Year by the Student Bar Association. Now in her second year, she’s topped that with a 1998 Distinguished Teaching Award. How did one so young hit the heights so fast?

The answer, surprisingly, is experience. Although she’s only been an official faculty member for two years, Ramasastry has been teaching much longer than that.

“I’m convinced it’s a calling,” Ramasastry says with a laugh. “It’s the one thing I’ve been consistently good at.”

Ramasastry began college at Harvard. During two summer terms she taught in a special program for junior high and high school students. The course she taught, appropriately enough, was law-related.

Although she chose to enter law school rather than take the academic path to a doctoral degree, Ramasastry didn’t stop teaching. She was a teaching fellow in both the government and history departments at Harvard and taught legal writing to first-year law students.

“When I first went to law school I thought I wanted to be an immigration lawyer, but inside six months I’d decided I wanted to be a professor,” Ramasastry says.

Inspired by her first-year professors, Ramasastry was disappointed with some of the rest of law school because of large classes where she didn’t participate. “I decided that I would never let my students be disengaged that way,” she says.

Not much chance of that. In Ramasastry’s first year contracts class, students learn concepts by participating in simulations, negotiations, mock trials, even by staging game shows.

The technique is a hit with her students. A letter signed by 20 of them says, “Using such techniques, Professor Ramasastry not only established a clear analytical framework for the entire course, she made the otherwise dry subject matter fun and interesting.”

Which sort of summarizes Ramasastry’s philosophy of teaching. “If you can make learning fun, you can push students to work hard and they’ll respond,” she says. “They won’t even be aware that you’ve turned so much responsibility over to them.”—Nancy Wick, UW News and Information

Excellence in Teaching Award

Frank Rothaermel

It’s no accident that the University of Washington has recognized Teaching Assistant Frank Rothaermel with a 1998 Excellence in Teaching Award. He works hard at it, takes it very seriously and sometimes goes above and beyond the call of duty. Rothaermel teaches courses in strategic management to M.B.A. students.

It’s no accident that the University of Washington has recognized Teaching Assistant Frank Rothaermel with a 1998 Excellence in Teaching Award. He works hard at it, takes it very seriously and sometimes goes above and beyond the call of duty. Rothaermel teaches courses in strategic management to M.B.A. students.

A native of Germany, Rothaermel earned his master’s degree in international economics and public policy in Germany and then got his M.B.A. at Brigham Young University. Rothaermel got his introduction to teaching at BYU when, as luck would have it, a couple of teaching assistant slots opened up.

“The first thing I did was sit down and think about who were the best profs I knew and why were they great instructors,” Rothaermel says. “I realized that these outstanding educators personified the following characteristics: caring, competent, passionate and patient.” The more he taught the more he wanted to give his students. “I am not only teaching them management theory but I make sure that these future leaders will know how to apply different theories in real world settings. I want to help them become more effective business people, but I also want them to be better citizens and leaders in their communities, families and volunteer organizations.”

His students praise not only his teaching skills, but his dedication to them as well. They recall a particular incident last October when he showed up a little late to his Executive M.B.A. class.

Rothaermel was tardy because he had collided with a car while biking to class from his home near Green Lake. The collision knocked him unconscious for a while. As he was being taken to the hospital in an ambulance, he managed to talk the attendant into letting him go and a police officer gave him a ride to class.

After conducting the review session, he went straight to the emergency room, where he stayed until the wee hours of the morning while doctors worked on his injured hip, dislocated shoulder and concussion. “He knew how important the review was to us and given everyone’s busy schedule, he didn’t want to let us down,” says Gregory Buckhardt, one of the students in the class.

His faculty mentor, Charles Hill, the Hughes M. Blake Professor of Management and Organization, says, “I think Frank Rothaermel exemplifies the best standards of excellence and dedication to teaching, to students well-being, and to the scholarly life.”—Paul Lowenberg, UW News and Information

Emily Silverman

Emily Silverman’s philosophy for teaching statistics is simple: Know your students.

Emily Silverman’s philosophy for teaching statistics is simple: Know your students.

This gets complicated, however, when you consider that as a teaching assistant for the Center for Quantitative Science in Forestry, Fisheries and Wildlife, her students are much more comfortable studying critters, crabs and conifers than they are studying coefficients.

“I get all kinds of comments about how much they hate quantitative stuff or how they’re no good at math,” Silverman laments.

Silverman’s ability to help her students overcome their aversion to most things mathematical is just one reason she has been awarded a 1998 Excellence in Teaching Award.

“I’m no longer afraid of statistics and feel like I’ve got a handle on things,” commented one of Silverman’s former students. “I’m amazed how interesting and useful this stuff is.”

Silverman, a 31-year-old Michigan native, receives equally rave reviews from faculty who have observed her work as a teaching assistant and instructor over the past two years. Silverman’s skills were particularly appreciated last year when she was asked at the last minute to teach a large, two-quarter statistical methods sequence after the original instructor fell through.

“Emily is what one would call a ‘born teacher,’ ” says Loveday Conquest, associate dean in the College of Ocean and Fishery Sciences. “This really makes a difference when you realize … quantitative methods, and especially statistics, probably wins the prize for ‘most dreaded set of required courses’ for biologically oriented majors.”

That is why it is so important, Silverman says, for her to know her students’ academic interests, skill levels and learning styles. Silverman starts with a short background assessment to find out how much they know. Then she scours books, newspapers and the Internet to find real-life examples relating course material to her students interests.

After graduating this summer with a Ph.D. in quantitative ecology and resource management, Silverman hopes to land a faculty position where she can continue to teach while doing research on ecological modeling.

“I enjoy the feedback you get in the classroom that you don’t necessarily get from doing research,” she says. “And I still feel like I’m making an impact on science by helping others understand their data—maybe even a greater impact than I could make with my own research.”—Greg Orwig, UW News and Information

Outstanding Public Service Award

Ed Lazowska

Like a proud parent, Ed Lazowska gets more excited when a student or faculty member in his department earns an award than when he wins recognition himself. Nevertheless, accolades keep pouring in for the energetic chair of the computer science and engineering department.

Like a proud parent, Ed Lazowska gets more excited when a student or faculty member in his department earns an award than when he wins recognition himself. Nevertheless, accolades keep pouring in for the energetic chair of the computer science and engineering department.

Lauded by community leaders such as Seattle Schools Superintendent John Stanford and State Rep. Tom Huff for his tireless volunteer work, Lazowska has been selected to receive the 1998 UW Outstanding Public Service Award.

“The range and impact of his public service is simply off the chart,” said a group of top university administrators. “We are convinced he never sleeps.”

Employing his signature style for problem solving—mastering the topic, devising new and sometimes unexpected solutions, recruiting key players to help carry them out and championing the cause with evangelical zeal—Lazowska has made his presence felt from the halls of local schools to the halls of Congress.

For example, he helped the Seattle Public Schools develop technology standards, raise funds and get more than one-third of schools connected to the Internet. He recruited nearly 100 UW faculty and staff to host an in-service day on teaching, learning and technology for Seattle teachers. And he has been a key player in the planning the K-20 network that will ultimately link all the state’s public educational institutions.

“The consequences of Ed’s substantial work is nothing less than helping to create an economic legacy for Washington,” wrote Kathleen Wilcox, president and executive director of the Washington Software Alliance, where Lazowska is on the board.

Adds Huff, chairman of the House Appropriations Committee, “The scope and quality of (Lazowska’s) service in support of economic development, education programs and policy, telecommunications policy, land use policy and tax policy is unprecedented in my experience. His service to Washington will remain forever in the network and related educational programs that will serve the children of this state.”

Simply put, Lazowska sees public service as an integral part of his job.

“It comes with the territory,” he says. “Not every person or every department needs to be engaged in every form of service, but as an institution we need to be out there. Computer science departments have unique opportunities and responsibilities because so much of the action, now and for the foreseeable future, revolves around information technology.”—Greg Orwig, UW News and Information

UW Recognition Award

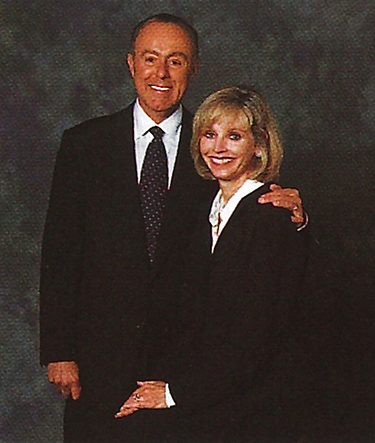

Jeff and Susan Brotman

Jeff and Susan Brotman bring an entrepreneurial spirit to everything they do. Jeff Brotman is best known as founder and president of Costco, the wholesale warehouse chain that sells everything from cauliflower to computers at a discount. He also led the 1997 Campaign for United Way of King County, and his marketing expertise brought unprecedented success to the annual fund-raising drive.

Jeff and Susan Brotman bring an entrepreneurial spirit to everything they do. Jeff Brotman is best known as founder and president of Costco, the wholesale warehouse chain that sells everything from cauliflower to computers at a discount. He also led the 1997 Campaign for United Way of King County, and his marketing expertise brought unprecedented success to the annual fund-raising drive.

Susan Brotman, a former Nordstrom executive, is known for her volunteer work, especially with Pacific Northwest Ballet and the University of Washington Foundation. She has chaired both of those boards of directors, and sees clear parallels between the profit and non-profit sectors: “You are gathering people together to solve problems,” she says.

For their service to the University and to the community, Jeff and Susan Brotman will receive the 1998 UW Recognition Award.

Susan Brotman is not a UW graduate, but Jeff has two UW degrees: after studying political science as an undergraduate and graduating in 1964, he went on to law school, earning his degree in 1967. While a student, he worked in the family business—Bernie’s, a young men’s clothing chain that catered to the baby boomers and had a store on the Ave. Although he expected his legal training to take him on a career path away from buying and selling, he soon found that his clients valued his business judgment as much as his legal skills. Now that he has focused on business, Jeff brings that approach to community service. For example, he realized that the United Way campaign needed a stronger identity, and “sold” the idea that it is a “safety net” for the community. People “bought” the idea by making donations.

“Jeff and Susan have generously given time, talent, and financial support to the University of Washington,” says President Richard L. McCormick. “What sets them apart, however, is that they consistently find ways to get other people to support the University. We’re very grateful that they bring their entrepreneurial instincts to their volunteer work here.”

“I feel a strong sense of gratitude to the University and the law school for helping launch my career,” says Jeff. “We want to give back to the community that has given us so much.”—Antoinette Wills, Office of Development

UWAA Distinguished Service Award

UW Alumnae Board

Josh Robinson came to the University of Washington with a big dream: getting an education in engineering or environmental biology. But paying tuition would not be easy for Robinson, the son of a single mother with limited resources.

But thanks to a scholarship from the Alumnae Board, he is a freshman with a 3.6 average and well on his way to a career giving something back to the community.

Every year since 1946, students like Robinson have enjoyed better lives because of the generosity of the Alumnae Board, which has been offering financial assistance to University of Washington students for the past five decades. It stands as the second largest contributor of scholarships (behind the athletic department) at the UW.

In the past four years alone, the all-volunteer Alumnae Board has funded nearly 100 full, in-state scholarships—contributions valued at $290,000. Without this financial assistance, many students simply would not be able to attend college. These students generally do not qualify for federal aid and tend to fall through the cracks.

For its legacy of hard work and generosity, the Alumnae Board received the UW Alumni Association’s Distinguished Service Award.

“We are very proud to be a part of this organization and to help as many students as we can,” says Kristen Lindskog Jarvis, ’82, the board’s president for 1997-98.

The majority of the funds for scholarships are raised at the annual Holiday Arts and Crafts Fair. The two-day fair—which will be held Sept. 2-3 at Hec Edmundson Pavilion and features the work of more than 120 Northwest artisans—is a long-standing event in the Puget Sound. What began as a simple arts and crafts display and sale in the early 1950s has blossomed into one of the largest shows in the area, with an estimated 5,000 shoppers attending annually.

Alumnae Board members—men and women who serve four-year terms—also select scholarship recipients, organize a scholarship luncheon, the Rhododendron Tea (the official reception at the President’s Residence), a spring social, and put together and sell a cookbook.

“Listening to the applicants’ stories is so inspiring,” Jarvis adds. “We regret that we can’t give each one a scholarship. The motivation these students have is remarkable.”—Jon Marmor, Columns

Distinguished Staff Awards

The University of Washington has expanded its awards program to honor staff members for their outstanding service to our community. Out of more than 100 nominees, the judges named five winners for 1998. UW Medical Center Patient Services Coordinator Cindy C. Farrell works in the Roosevelt pediatrics clinic and was cited for her caring attitude toward patients and their families. Telecommunications Services Manager Scott Mah was honored for designing and maintaining digital systems that link UW people to other campuses and the world, and for his help in building the state’s K-20 telecommunications network. RN Supervisor Brenda K. Montgomery is the program coordinator for the UW Diabetes Prevention Program and was recognized for her community outreach and her research planning efforts. Gardener Kristen C. Spexarth tends about 20 acres of the UW campus, including the grounds of the President’s Residence, and was honored for her creativity, enthusiasm and innovation in garden design. Machine Mechanic Supervisor Tom Wade is responsible for repairing and maintaining equipment in the dental school and was cited for his dedication and innovation, including designing the school’s simulation lab, a model for dental schools across the nation.