Brian Sternberg soared as a pole vaulter until fateful accident

As a teen-ager, he flew higher than any human being on his own power. Then a 19-year-old sophomore at the University of Washington in the summer of 1963, Brian Sternberg shattered the world pole vault record three times, soaring to a best of 16 feet, 8 inches.

As a teen-ager, he flew higher than any human being on his own power. Then a 19-year-old sophomore at the University of Washington in the summer of 1963, Brian Sternberg shattered the world pole vault record three times, soaring to a best of 16 feet, 8 inches.

He was an NCAA track champion and was invited to represent the United States in a dual meet against Russia at a time when the Cold War was white hot. “I think he would have been the first to clear 20 feet,” says Stan Hiserman, Sternberg’s college coach. “He was only a sophomore and really just getting started with the event.”

But three days before he was to leave for Russia, a routine gymnastics workout turned out anything but routine. Sternberg bounced from a trampoline, shot 15 feet into the air and did a double somersault with a twist. It was an exercise he had done thousands of times. Only this time, he landed on his head. He has been paralyzed ever since. That was 34 years ago.

For nearly three and a half decades, he has been in a wheelchair and in excruciating pain. Two years ago, however, an American doctor working in Germany rerouted tissue from the stomach area to the damaged section of Sternberg’s spine, adding a rich, new blood supply. For the first time in decades, Sternberg could scratch his nose.

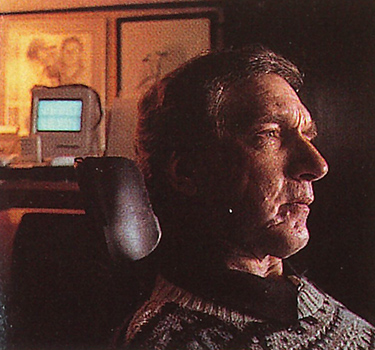

The surgery gave him movement in his right arm and increased motor control. “I’m much stronger, and I can speak better too,” says Sternberg, 53, who still talks in a soft, breathy voice, and punctuates his words with pauses.

Sternberg lives in his mother’s house in the Queen Anne district of Seattle. “He has never given up an ounce,” says his mother, Helen. “In his mind, he is still an athlete.”

In his day, he was strong and agile, a gymnast who made a seamless transition to pole vaulting. His aerobatic ability on the trampoline and the use of a flexible pole made him a star. He first cleared 16 feet in March of his sophomore year, then bettered that by eight inches in just two months. Meet directors from all over the world sought him.

He was also fearless. Only days before his accident, Sternberg told reporters he never feared gymnastics, that pole vaulting was much more dangerous than gymnastics. He even performed comedy routines on the trampoline, taking pratfalls to amuse fans.

But when he landed head first and dislocated a cervical vertebrae that day in June, it was dead serious. He recalls “seeing my arms and legs bouncing around in front of my eyes and not being able to do anything about it, he says.

In the months following the accident, Sternberg received 5,000 letters. Even President and Mrs. Kennedy wrote.

But soon everyone else got on with their lives. Brian’s insurance with the University ran out in six months. The Brian Sternberg Trust Fund was established and a big fund-raising dinner was staged to raise much-needed money. The trust fund is still open and accepting donations through Seafirst Bank.

“What good would being bitter do,” says Sternberg, who was inducted into the Husky Hall of Fame in 1983 and occasionally attends Husky basketball games and Mariner games.

“I’m angry that I can’t still do some things, and I’ve been very disappointed, but not bitter. The biggest thing is frustration over not being able to be heard.”