Cold War-era ballet tours were high-stakes artistic displays

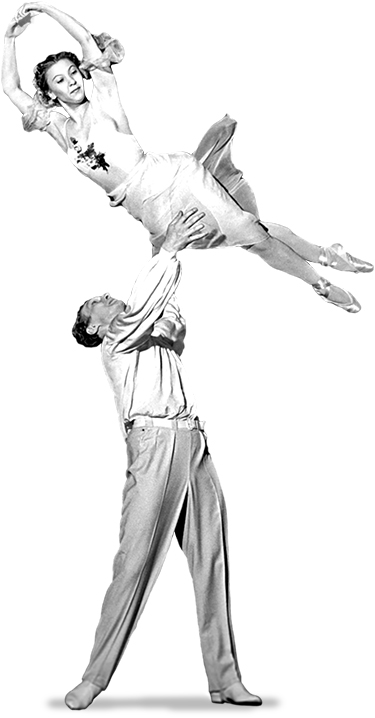

Alexander Lapauri and Raisa Struchkova of the Bolshoi performed on U.S. stages for the first time in 1959 and again in 1962.

The Cold War played out on exotic battlegrounds. Perhaps none were stranger—and had more unexpected outcomes—than the four cultural-exchange ballet tours in which elite artists jetéd for national supremacy in tutus and tights.

“In many ways these tours were about the U.S. and Soviet governments staking out claims for controlling the rest of the world,” writes Anne Searcy, an assistant professor in the School of Music, in her book “Ballet in the Cold War.” She reveals that dazzled audiences in both nations reacted in unexpected ways and that ballet in both nations had more in common than either side wanted to admit.

The Italian Renaissance gave birth to ballet, but Russians dominated the art to such a degree no one questioned their supremacy. The Bolshoi, the world’s reigning company, pirouetted onto U.S. stages in 1959 and 1962. The State Department-sponsored American Ballet Theatre (ABT) went east in 1960 followed two years later by the New York City Ballet (NYCB), led by its Russian émigré choreographer George Balanchine. Adding a thermonuclear layer of stress, the Cuban Missile Crisis ignited in October 1962 when the Bolshoi and the NYCB were in each other’s countries.

Upstart Americans left home unproven underdogs. Searcy, who fell in love with Soviet-era ballet while studying Russian in St. Petersburg, says some even asked, “Can ballet be American?” Nerves showed when critics joked the Bolshoi would “conquer” America. The New York Times feared a “profound national humiliation” might result if the ABT disappointed the folks back home.

But audiences in both nations went wild. The Bolshoi’s artistic director wrote to his wife that people screamed, cried, and tore up their programs after an audience demanded 17 curtain calls. Scalpers resold tickets for the equivalent of $830 in 2018 dollars. It became clear, according to Searcy, that balletomanes in both nations felt safe praising dancers for their virtuosity. But no one dared say the visiting companies were better, especially regarding their artistic philosophies.

Cultural misunderstandings hobbled both sides. The Bolshoi flopped with “Spartacus,” a ballet about a Roman slave uprising. A Hollywood epic of the same name had just opened. The Soviets thought their extravaganza would do boffo biz while sneaking its true meaning—a depiction of proletariat revolt—past unsuspecting audiences. “To American eyes, the work did not even look like a ballet,” says Searcy. “The dancers wore flat Roman sandals, not pointe shoes, and Americans could go see a movie for less than a dollar. They booed it.” Backstage, the Russian choreographer wept. The ballet was scratched from the schedule.

Americans predicted abstract ballets like Balanchine’s “Agon” would offend literal-minded Soviet apparatchiks. While Russian critics chastised their cold style, they praised the choreographer’s “inexhaustible imagination.” Searcy says they saw “deep similarities” between his neoclassical style and choreographic symphonism in their own country.

To Americans’ surprise, their hosts discouraged them from performing Jerome Robbins’ “Afternoon of a Faun” because of its sensuality and Agnes deMille’s “Billy the Kid.” “Soviet works were supposed to demonstrate that the world was constantly improving, moving through a dialectic struggle into a glorious future,” writes Searcy, not celebrate midday delights or some punk outlaw.

Just as astronauts and cosmonauts sought to literally fly higher than each other, in ballets like “Spartacus” and the Americans’ “Rodeo” and “Fancy Free,” male dancers did the same. They wielded swords, rode imaginary bucking broncos, and brawled like drunken sailors. Surprisingly, post-war ballet in both countries “glorified the very masculine working-class man,” says Searcy, with works whose “strong dancing showed off big jumps and big spins,” not genteel aristocratic male footwork.

No one out-machoed Balanchine—not Khrushchev, who went stag to a Moscow show, or a dapper President Kennedy in black tie. Balanchine had fled the USSR in 1924, had not returned since, and in the intervening years had become recognized as one of the 20th-century’s great artists. His dozens of breathtaking works included “Stars and Stripes.” Set to John Philip Sousa’s martial marches, its finale featured a colossal American flag.

Upon arriving in Russia, an interviewer said, “Welcome to Moscow, home of classic ballet.” Balanchine shot back, “I beg your pardon. Russia is the home of romantic ballet. The home of classic ballet is now America.” Translation? Your ballets are mud. I own ballet’s future. While Searcy dubs him an “appalling ambassador,” she adds, “On an emotional level, I understand what he did. He was quite a patriotic American. He really, really didn’t like the Soviet government.”

When the dancing duels ended, there was no clear winner, according to Searcy, except ballet fans. People in both countries gained respect for far-away artists, especially when Russian ballerina Maya Plisetskaya performed “The Dying Swan” solo from “Swan Lake” for an audience of 11 million on the Ed Sullivan TV variety show. Like artistic minutemen, Britain, Germany and Japan soon had their own national ballet companies.

“The Cold War made ballet feel more important, more international,” says Searcy. Before the international exchanges, ballet was Russian. Afterward, it belonged to the world.