Crows know their foes from their friends on campus

Oregon may be one of the UW’s archrivals, but anyone who has spent time on the Seattle campus in June will tell you that the crow, not the duck, is the Huskies’ true nemesis.

Oregon may be one of the UW’s archrivals, but anyone who has spent time on the Seattle campus in June will tell you that the crow, not the duck, is the Huskies’ true nemesis.

Crow fledglings begin leaving the nest in late spring, and it’s not uncommon for hapless passersby—Columns editors included—to be scolded, stooped upon and even struck by the overprotective parents.

City crows are particularly aggressive says John Marzluff, a College of Forest Resources professor who has studied crow behavior for decades. It’s not that mean streets produce mean birds. On the contrary, Seattle crows are probably bolder than their country cousins because they know they’re in no danger of being shot.

“What we’ve found out,” Marzluff says, “is that they’ve basically changed their culture in response to how our culture treats them.”

“What we’ve found out,” Marzluff says, “is that they’ve basically changed their culture in response to how our culture treats them.”

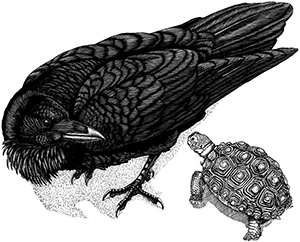

Marzluff chronicles this coevolution in a new book he wrote with artist Tony Angell, ’62. In the Company of Crows and Ravens, which Yale University Press will publish in October, is a study of interspecies dynamics from antiquity to the present day, illustrated with more than 100 of Angell’s original drawings.

Marzluff knows UW crows pretty well—and vice versa. His research involves capturing them with cannon nets, putting socks over their heads to pacify them, and attaching colored bands to their legs. Birds with anklewear are a common sight around campus. The trouble is, crows have extraordinary memories—Marzluff has demonstrated that they can identify the McDonald’s logo on a bag of food—and they tend to hold grudges. As a result, Marzluff and his graduate assistants face the prospect of aerial bombardment every time they set foot on campus.

Marzluff knows UW crows pretty well—and vice versa. His research involves capturing them with cannon nets, putting socks over their heads to pacify them, and attaching colored bands to their legs. Birds with anklewear are a common sight around campus. The trouble is, crows have extraordinary memories—Marzluff has demonstrated that they can identify the McDonald’s logo on a bag of food—and they tend to hold grudges. As a result, Marzluff and his graduate assistants face the prospect of aerial bombardment every time they set foot on campus.

Perhaps they would be safer travelling incognito. A researcher in England famously donned a Santa Claus suit to do his crow capturing. “We’ve actually thought about that,” Marzluff says.