War is sexy. Huh?

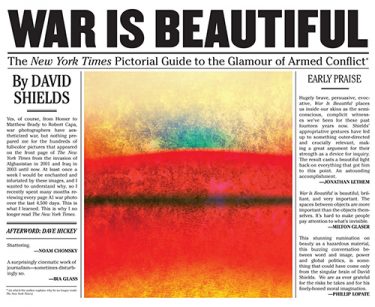

You need guts to take the New York Times to task. But that's exactly what David Shields, author, essayist and UW English professor, does in his book, “War Is Beautiful: The New York Times Pictorial Guide to the Glamour of Armed Conflict.”

Why did you publish the book?

Why did you publish the book?

For decades, I was entranced and infuriated every morning by the war photographs in The New York Times, from the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 and Iraq in 2003 until now. I wanted to understand why.

What’s your opinion of those photos?

The paper’s design department is running the paper’s war photography department. Picture after picture looks like a Gerhard Richter or Jasper Johns painting. They have a butterfly-pinned-to-the-wall quality.

Why is that problematic?

Matthew Brady’s photographs of the Civil War are beautiful, but they’re also documenting the horror of war. These emptily beautiful photos in The Times function as war cheerleading.

Why do you think these photographs are different from those of prior wars?

There is a whole series of reasons for the changes in war photography, including the embedding of photographers. If you’ve been in the mess hall with a guy at lunch, are you really going to take the photograph that documents his horrible death?

What do the photographers who take these pictures have to say?

A lot of photographers will tell you off the record that they’ll get calls from editors that say, “We need a little orange in the picture. Do you have any images of a dying soldier with an orange sunset—because we need it for the page.”

How did you go about selecting the photos in the book?

My UW research assistants and I looked at almost 25 years of front-page photos, about 9,000 in all; of 1,000 color war photos on the front page, we found 700 images that seemed less invested in documenting the war than in selling the war by making it seem harmless or sexy or perhaps both.

How is the book selling?

Pretty well, I believe, but far more important to me is that it’s generating a lot of discussion in newspapers and magazines and in broadcasts and on the Web all over the world.

Did you consider other approaches to the book?

Not really. At one point, I thought of making the entire book focused on photos as war movie, since I found so many such photos.

Why do you think The New York Times publishes pictures like this?

That’s the $64,000 question, isn’t it? There are a multitude of reasons, from maintaining access to the highest levels of government to trying to survive to building its brand to trying to occupy the center of national conversation.

If we can’t turn to The New York Times for war coverage, what can we do?

I want us to look more toward independent, citizen reporters and citizen photographers. A lot of the best work coming out of Afghanistan and Iraq has been done by independent bloggers. The Times is much too complicit with the manufacture of consent.