Books: Meet the beetles (and other ‘Everyday Creatures’)

Biology professor Jim Kenagy takes in the surprising beauty of ordinary life in wild places.

Forty years ago biology professor Jim Kenagy set out for Frenchman Coulee near Vantage, Washington, with a group of students to meet the beetles. Not the rock band from Liverpool but a type of desert beetle. And for Kenagy and the students, the weekend spent observing and documenting the behavior and characteristics of the wiggly-legged insects really was a magical mystery tour.

Kenagy is a professor emeritus of biology who spent 40 years teaching at the UW. He’s also a retired curator at the Burke Museum. His specialty is small mammals like the golden-mantled ground squirrel or your garden variety chipmunk.

On the 40th anniversary of the beetle trip Kenagy reached out to some of the students with emails and calls reminding them of their hourly beetle counts, measurements of beetle body temperature and other processes.

“I do have a special fondness for those particular beetles. I even took my grandson who was age seven to Frenchman Coulee to see the beetles,” Kenagy says. “I had hoped for lizards and I had promised him a rattlesnake. It was cold but the beetles were out and about and he did find two scorpions. It was great to re-immerse myself in beetles.”

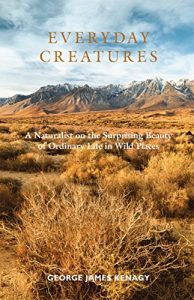

Kenagy is finding a second career in retirement. This last spring Dockside Sailing Press of Newport Beach, Calif. published “Everyday Creatures,” a collection of 13 essays. One of those essays is the story of the weekends the students spent observing what Kenagy describes as “beetles of a charming and gentle sort.”

To this day Kenagy loves nothing better than striking out on a camping trip into various natural settings to document the behavior and traits of creatures he enjoys, like the kangaroo rat. I admit that Kenagy’s book moved me from a position of screaming horror atop the kitchen table at the thought of a kangaroo rat to one of mild yet squeamish appreciation. Here’s his engaging description of the species, which he observed during his student days at Pomona College:

“This little two-ounce rodent, with an oversized head, a body about four or more inches long, and a tail nearly once and half again that long, was capable of bipedal hopping. … It remained still momentarily, groomed itself a bit with its tiny front paws, rubbed its shoulders and flanks in the sand, stood steadily again, and then launched itself like a shot across a short space of open terrain, with its long, stiffened tail wavering behind as a counterbalance to each simultaneous downward thrust of its powerful hind legs that propelled the animal forward in leaps of three feet or more in length.”

You have to admit that it’s a cunning description of one rodent’s travel across the Mojave desert. Kenagy is a close observer of the little mammals he cherishes. Not surprising for a biologist, but not all biologists can charm.

Take the chapter titled “Taking a Walk with a Beaver.” Kenagy recalls visiting a small, East Coast college and meeting a beaver on an evening stroll around a small lake. Together, man and beaver seem to become conscious of one another, a kind of meeting of the minds of the members of two distinct species:

“We continued, my steps matching the gentle strokes and propulsion of his legs and tail, coupled only with his subtle steering, none of which I was actually able to see below the surface. We reached the upstream end of the lake. I didn’t want this to end.”

Other chapters include his account of stalking the wild iguana near Palm Springs in 1964, his acquaintance with ants, tracking the scat of a giant panda in China (which he describes as looking like a giant baked potato) and more.

If you’re looking for a beach read this summer, skip Tom Clancy and spend some time with Jim Kenagy taking in the surprising beauty of ordinary life in wild places. You’ll be glad you did.