The story of University of Washington football is, predictably, a story of giants—giants such as Gilmour Dobie, whose teams ran the off-tackle smash with metronomic precision. And James Phelan, who made bench coaching an art. And Howie Odell, whose Flying Circus in the '50s was a weekly numbers machine. And Jim Owens, whose Purple Gang in the '60s brought respectability back to West Coast football. And Don James, whose string of bowl teams set a standard of excellence on the Pacific slope.

The story of University of Washington football is, as well, a story of heroes—heroes such as George Wilson, the enigmatic All-American of the ’20s whose battles with Ernie Nevers and Red Grange thrilled spectators. And Hugh McElhenny, whose signature was the mind-boggling run. And Don Heinrich, the first of the great West Coast passers. And Sonny Sixkiller, who practically became a cottage industry.

The story of University of Washington football, beyond the memorable games, the wondrous plays, even the unfathomable foibles, is also a constant catalog of surprises.

What other school, after all, received its colors from Lord Byron? What other school lured Chief Joseph, the famous Nez Perce Indian, out of the mountains and turned him into perhaps the first sideline commentator in college football history? What other school can lay claim to a 63-game unbeaten streak on the one hand and the invention of The Wave on the other?

The following moments from University of Washington football history were selected not because they tell the entire story—you need a whole book for that—but because they provide a flavor of the first 100 years.

The UW won its first football game on Dec. 17, 1892, beating the Seattle Athletic Club, 14-0, at Madison Park, one of the many fields the school used for games before Denny Field was constructed. J. Harvard Darlington played quarterback, and Frank Atkins, the team’s fullback, scored the first touchdown in UW history on a five-yard run in the second quarter.

“The first two times Atkins tried to dropkick the goal (extra point), the ball hit the ground only 20 feet away,” Darlington recalled many years later. “After our third touchdown, Captain (Otto) Collings had me kick the ball. I told him to hold it and I kicked it over for Washington—the first kicking point in school history.”

The Seattle Times made these comments following Washington’s first victory: “At the end of the second half, the Seattle team was covered with mud and defeat. If the system of mathematics in the regulations of the football code recognized such a thing as a third half, there would have been a coroner’s inquest.”

The Seattle Post-Intelligencer focused on the postgame celebration: “A good-sized company paraded the streets, shouting the university cry with all the power of their sturdy young lungs. … The winning team dined at the Rainier Hotel, where a spread was prepared at the instance (sic) of manager Lee Willard. The event took on the semblance of a banquet, every member of the team responding to a toast. It wound up with three cheers, first for manager Willard and then for Capt. Collings.”

Perhaps no football game in Washington’s first 15 years got Seattle quite as excited as the Washington-Nevada match-up on Nov. 20, 1903. The championship in question carried with it bragging rights to the whole West Coast. Washington had won the Northwest Athletic Association title after beating Oregon, 6-5, and Nevada had knocked off California and tied Stanford. But the game itself had few fireworks. The main excitement for the crowd of 5,000 at Athletic Park occurred when Friesell, the Nevada kicker, was unable to punt out of his end zone because the ball was snapped over his head, giving Washington a safety. Washington, an eventual 2-0 winner, had a subsequent scare when Friesell broke loose on a long run, but Enoch Bagshaw saved the day by tackling him in the open field.

The title was the first of consequence in Washington football history. Remarked the Times, “Seattle wasn’t large enough last night, and never will be large enough to hold the backers of Washington.”

Another interesting feature of the afternoon was the appearance of Chief Joseph, the famous Indian. The Nez Perce chief, also making his first visit to Seattle, watched the contest from the sidelines and was not overly impressed with the proceedings. “I saw a lot of white men almost fight today,” Chief Joseph explained. “I do not think this good. This may be all right,” but I believe it is not. I feel pleased that Washington won the game. Those men I should think would break their legs and arms, but they did not get mad. I had a good time at the game with my white friends.”

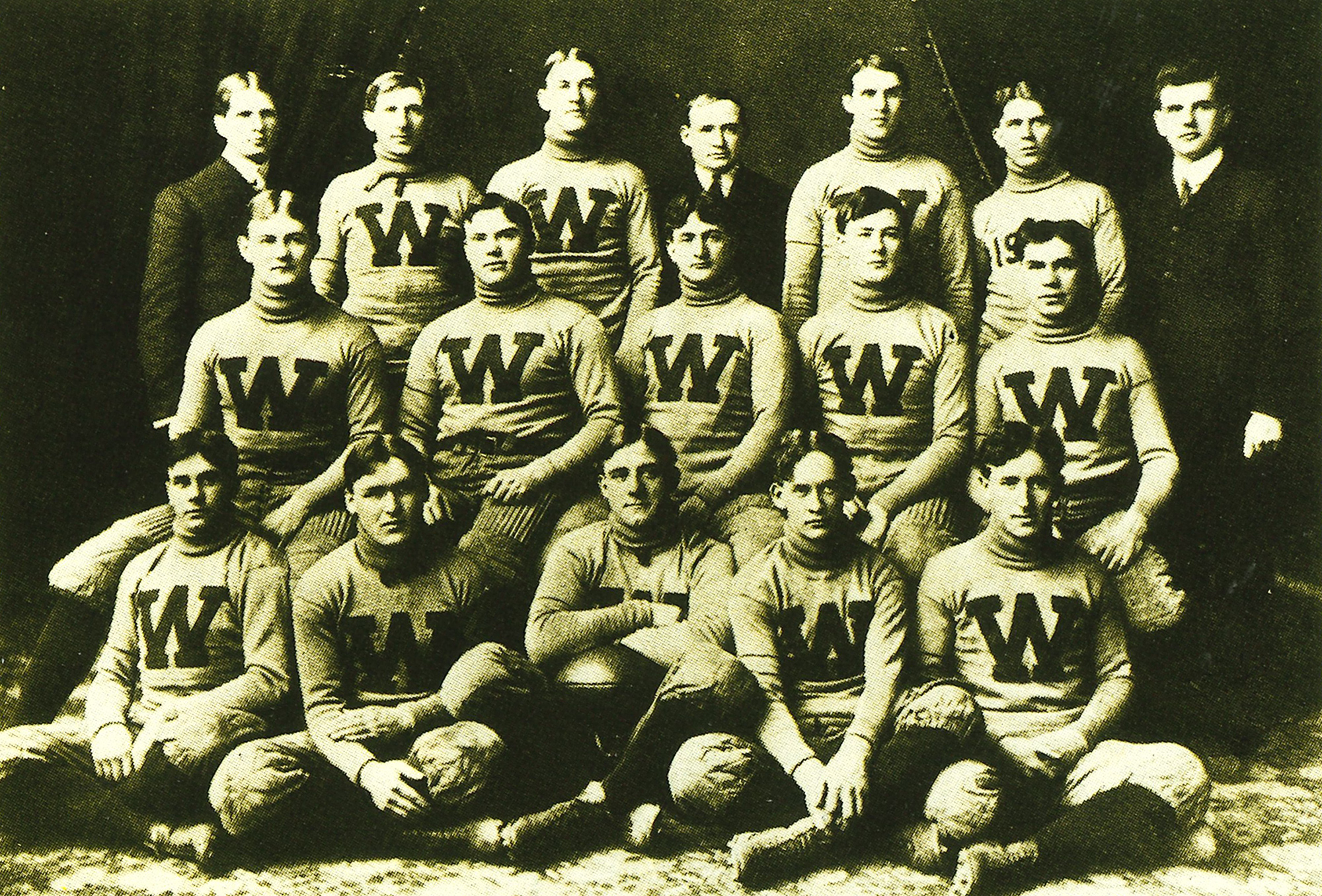

(The 1903 team is pictured at top.)

Gil Dobie

He had many aliases, but more than anything Gilmour “Gil” Dobie should be recognized as the founder and father of Husky Fever. In his nine-year reign at the University of Washington, the dour, aloof, brilliant coach left a winning football legacy no collegian anywhere has equaled. A tall, lean man with black hair who often wore a slouch felt hat and a long, black overcoat, and who smoked cigars or chewed on straw as he paced the sidelines, Dobie never suffered one defeat through those nine football campaigns, spanning the years 1908-16.

Oh, the fabulous Dobie men didn’t win them all—they were tied three times—but when he stepped down in December 1916, his UW record was a mere smidgen shy of flawless: 58 victories, no losses, three ties, nine championships, 1,930 points scored (an average of 31.6 per game), 118 points allowed (less than two points per game).

Still, Dobie is almost more remembered as a prophet of gridiron doom than for his skilled teams and accomplishments. The nicknames which tracked him through his 33-year college coaching career (182-45-15) were “Gloomy Gil,” the “Sad Scot,” the “Dour Dane,” and the “Apostle of Grief.” His never-failing trait of predicting dire defeat or disaster before each Washington game also provided sportswriters with a new synonym—“Gildobian”—for sad and gloomy.

But this austere man with the piercing eyes was a no-frills technical and psychological master of football and the men who played it. He made pessimism pay off in a manner that has never been duplicated. The main irony with regard to Dobie’s tenure at Washington is that although Dobie never lost a game, he was fired following a dispute with UW President Henry Suzzallo. Another irony is that Dobie, who was hired at a sum of $3,000 a year, was only making $3,100 at the time of his dismissal. So after the 58 wins and no defeats, he’d only earned a $100 raise.

Many observers felt that the Washington-Whitman game of Oct. 25, 1919, would soon be reduced to a historical footnote since the Purple and Gold had made an annual habit of pummeling the Missionaries. While Washington had won five straight meetings between the schools by a combined score of 136-25, none of the 5,000 spectators who gathered at Denny Field was prepared for a dismemberment for the ages. Enjoying a 30-pound weight advantage per man, Washington practically conducted a track meet in sprinting to a school record 19 touchdowns—seven of which were scored by halfback Ervin Dailey—en route to a 120-0 victory.

On his TDs alone, Dailey amassed 350 yards rushing, which would have been a school record if official statistics had been kept. The game featured one notable amusement. In the second half, Washington’s Gus Pope somehow tore a huge hole in his pants, and the rout had to be put on hold while trainer “Hec” Edmundson hurried on the field to stitch the tackle’s trousers back together.

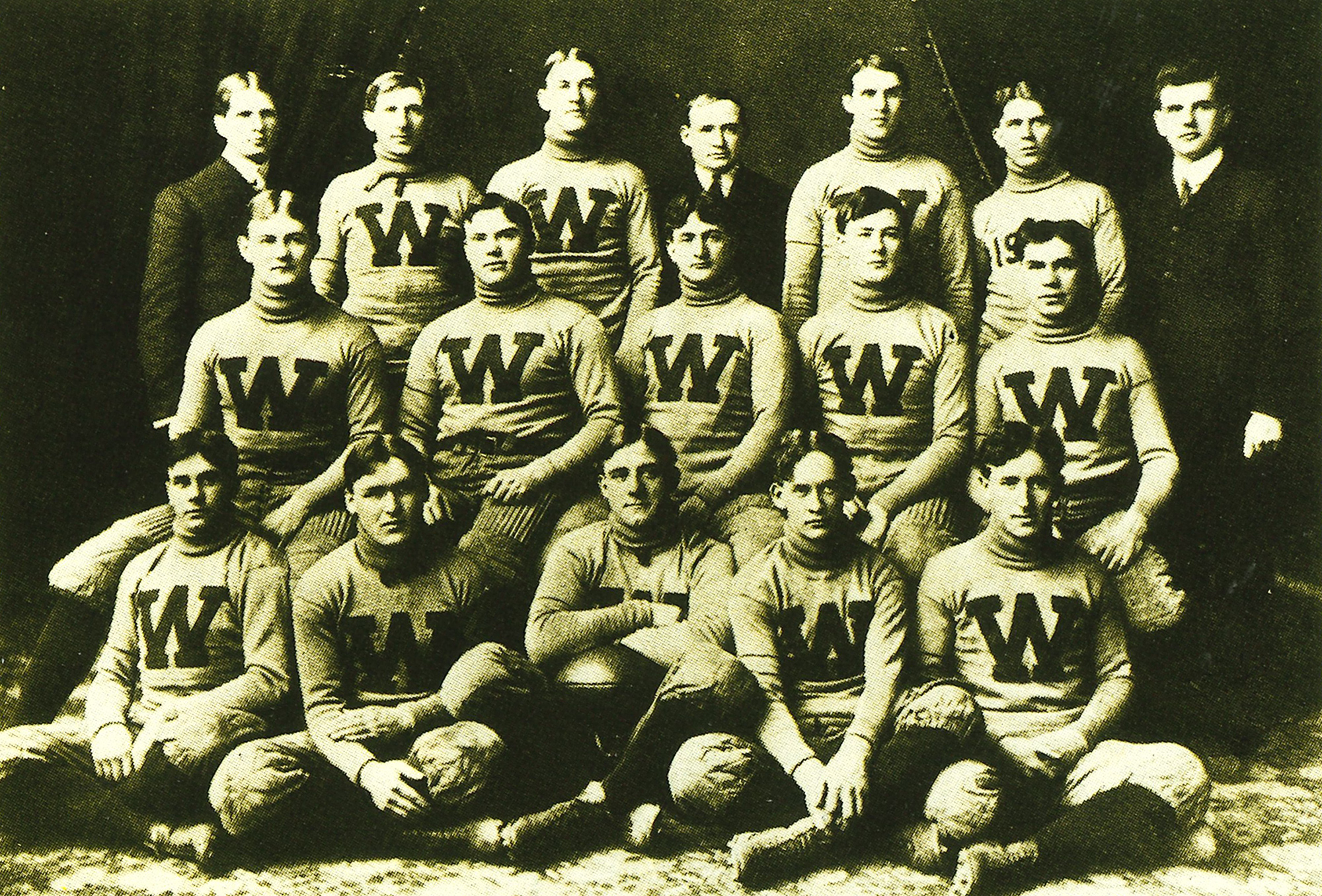

While great games weren’t a rare occurrence for All-America halfback George Wilson, his performance against Alabama in the 1926 Rose Bowl was arguably his finest hour. Wilson not only upstaged future movie cowboy Johnny Mack Brown in Washington’s 20-19 loss, he turned the game into a one-man show.

While great games weren’t a rare occurrence for All-America halfback George Wilson, his performance against Alabama in the 1926 Rose Bowl was arguably his finest hour. Wilson not only upstaged future movie cowboy Johnny Mack Brown in Washington’s 20-19 loss, he turned the game into a one-man show.

In the first quarter, Wilson intercepted a pass and had a 25-yard run to set up Harold Patton’s one-yard TD. In the second quarter Wilson pranced 36 yards from punt formation, then threw a 20-yard TD pass to John Cole. Washington seemed certain to win—until Wilson was injured late in the second period. With Wilson out, Alabama rallied, scoring all 20 of its points in seven minutes of the third quarter. Wilson returned in the fourth and threw a 28-yard TD pass to George Guttormsen, but the Huskies couldn’t overcome the damage Alabama had done when Wilson was out.

In all, Wilson played 33 minutes, rushed for 134 yards on 15 carries—an 8.9 average—and completed five of 11 passes for 77 yards and a pair of TDs. Washington amassed 317 yards and scored 19 points while he was in the game. During the 25 minutes he was out, Washington managed just 17 yards.

Ironically, Wilson would not have had the opportunity to play the best game of his career if Washington’s players had not rescinded their vote against going to the Rose Bowl. After receiving the invitation, the Huskies twice rejected the trip because they weren’t thrilled about being away from home for Christmas.

After the 1925 season, Wilson was named a first-team All-American in a backfield that also included Red Grange of Illinois.

Hugh McElhenny

Entering their annual showdown with Washington State on Nov. 25, 1960, the 7-2 Huskies seemingly had nothing to play for. They’d already been knocked out of the Rose Bowl race by California. But that fact was clearly lost on Hugh McElhenny and Don Heinrich.

McElhenny romped for an all-time school record 296 yards and scored a modern-day record five TDs on sprints of 23, 39, 7, 14 and 84 yards. Heinrich, meanwhile, set a national completion record with his 134th of the season as the Huskies won, 52-21.

How Heinrich’s record came about constitutes an intriguing piece of Husky lore. Early in the fourth quarter, with Washington leading, 45-14, UW Athletic Director Harvey Cassill learned that Heinrich had tied the completion record of 135, set by Chuck Conerly of Mississippi in 1947. What surprised Cassill was that he thought Heinrich had already broken the record.

So Cassill relayed word of the statistical deficit to the Washington bench. The only thing wrong was that WSU had the ball and time was running out. But UW tackle Clyde Seiler had an idea: Let the Cougars score so that the Huskies could get the ball and give it to Heinrich. On the next play, WSU’s Dick Gambold tossed a 21-yard TD to John Rowley while Husky DB Dick Sprague simply stood and watched the action with his hands on his hips.

On the subsequent Washington series, Heinrich completed a pass to Phil Gillis to set the completion record. Not only did Heinrich get the record, but moments later McElhenny got loose for an 84-yard TD run to set a new single-season conference record of 1,107 yards. Heinrich’s single-season completion percentage of .606 lasted for 33 years until Steve Pelleur finished with a .672 mark in 1983. McElhenny’s record lasted until 1978 when Joe Steele accumulated 1,111.

Although Washington finished the 1959 season with a 9-1 record, good for a Number 8 Associated Press ranking, oddsmakers were hardly infatuated with the Huskies’ chances against Number 6 Wisconsin (7-3) heading into the 1960 Rose Bowl.

In the first place, Washington hadn’t been to a Rose Bowl in 22 years and seemed to be one of those curious interlopers who drop into Pasadena from time to time. In the second place, West Coast teams had served as New Year’s fodder for the Big Ten as long as anyone could remember.

But if Washington gave no inkling that history was about to change, the first quarter removed any doubt. Don McKeta scored on a six-yard run, George Fleming kicked a 36-yard field goal and returned a punt 53 yards for another TD, and the 44-8 rout was on. Although the Badgers got eight points back on a TD and two-point conversion, QB Bob Schloredt retaliated with a 25-yard TD pass to Lee Folkins and the Huskies led, 24-8, at the half. By the time it was over, Washington’s Purple Gang had run up 44 points and stuffed the Badgers every way imaginable.

Fleming and Schloredt were named co-players of the game, and Washington had its first Rose Bowl triumph after three previous failures. Washington’s victory began a reversal of Rose Bowl dominance. Before the Huskies’ triumph, Big Ten teams had won 11 of the previous 12 Rose Bowls. Beginning with this victory, Pacific Conference teams won 12 of the next 18 games. In fact, Washington’s Purple Gang also won the next Rose Bowl by beating Minnesota, 17-7, in 1961.

The Washington-Michigan State opener on Sept. 19, 1970, didn’t hold much promise for the Huskies, who had finished 1-9 in 1969 and hadn’t had a winning season in three years. In fact, the 1970 Huskies had already been picked by Seattle-area sportswriters as the team least likely to succeed in the Pac-8 Conference.

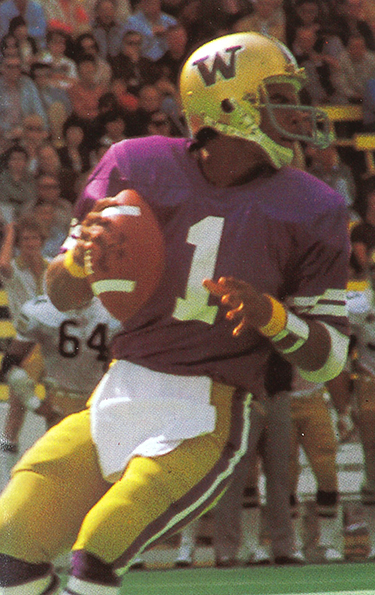

There was, however, one important change in the team’s composition: a new quarterback with the intriguing name of Sonny Sixkiller. Although Sixkiller had been regarded as an untested sophomore going into the game, he was well on his way to becoming one of the most idolized football heroes in Husky history.

Sixkiller led the Huskies to a touchdown on their first series, and went on to lead Washington to several more, en route to a 42-16 win. Sixkiller’s performance so impressed the Associated Press that it named him its National Back of the Week.

Sixkiller was chosen Pac-8 Back of the Week five times during the 11-week season in which he set a number of records, including most passing yards (360) in a game, most yards (2,303) in a season, most completions (30) in a game, most completions (186) in a season and most TDs (15) in a season. Sixkiller ultimately became one of only two Washington players to make the cover of Sports Illustrated. The other was Bob Schloredt, who was pictured on Oct. 8, 1960.

A Cherokee Indian, Sixkiller was so popular there was a hot-selling record about him: “The Ballad of Sonny Sixkiller.” There were “6-Killer” T-shirts, a “6-Killer” fan club. There were Sonny Sixkiller postcards, Sonny Sixkiller headbands, Sonny Sixkiller this, Sonny Sixkiller that.

Sixkiller even had the most scrupulous Seattle sportswriters salivating. In fact, it got ridiculous and sometimes rather offensive. One scribe tastelessly described Sixkiller as “the most celebrated redskin since Crazy Horse.” During the Sixkiller era, it was amazing how many media people could not resist reporting that the Washington quarterback had “scalped” and “massacred” teams up and down the Pacific Coast.

Sixkiller was so popular that the Washington athletic department received dozens of fan letters per day addressed to him. Sixkiller even received one piece of mail with nothing on the front of the envelope except a drawing of the sun and the number “6.”

Warren Moon

In the beginning of October 1977, the season looked like a wash for the Huskies as Minnesota beat them Oct. 1 with a last-minute field goal. Instead, Washington won six of its last seven games and earned its first Rose Bowl berth in 14 years.

There were two highlights to the turnaround: a 54-0 thumping of Oregon and a 28-10 triumph over USC. Those victories not only plowed Washington’s Rose Bowl path, they vindicated Husky QB Warren Moon, who had been an object of fan vilification. But Las Vegas philosophers disputed the idea that Washington would saddle Bo Schembechler with his fifth bowl loss in five tries, instead making the Huskies 14-point rejects.

But with a wide-open offense guided by Moon, the Huskies led, 17-0, at halftime and made it 24-0 early in the third period. The Huskies seemed out of Michigan’s reach, especially considering Big Ten teams had always been awful at coming from behind. But Wolverine QB Rick Leach threw a 76-yard TD pass and then orchestrated another TD drive. With almost a quarter to play, it was 27-14. Then Leach tossed yet another TD pass.

But the Washington defense got out of its dither just in time. LB Michael Jackson intercepted a Leach pass on the Washington eight, and Nesby Glasgow stole another Leach offering on the Washington seven with 32 seconds remaining, preserving the Huskies’ 27-20 triumph. Moon, who ran for two TDs and threw for a third, was selected Most Valuable Player.

The 1978 Rose Bowl team was perhaps the most significant club in Husky football history. On the basis of Washington’s win, Coach Don James was able to recruit players who went on to form the nucleus of the 1981 and 1982 Rose Bowl teams.

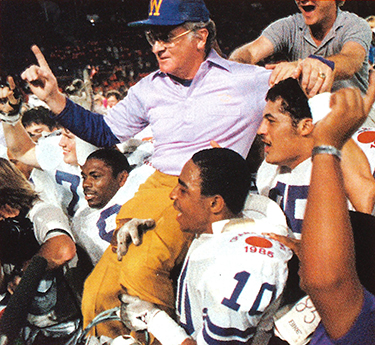

Coach Don James led the Huskies to an Orange Bowl victory on Jan. 1, 1985.

With undefeated Brigham Young entrenched atop the polls and a BYU Holiday Bowl victory in hand, there seemed little chance 10-1 Washington would be able to ascend to Number 1 even with a victory over Number 3 Oklahoma on New Year’s Day 1985 in the team’s first Orange Bowl.

Paying no heed to that, the Huskies ran up a 14-0 lead on a Paul Sicuro TD pass to Danny Greene and a one-yard run by Jacque Robinson. Oklahoma, whose wishbone had been throttled in the first quarter by a trapping Washington defense, struck for 14 points in the second period and made it 17-14 with a field goal midway through the third.

It was then that Coach Don James decided to replace Sicuro with Hugh Millen. James hardly looked the genius when, on Millen’s first pass attempt, he threw the ball in the dirt. But two plays later, Millen completed a 29-yard strike to Greene. Four downs later, Millen aired it out to Mark Pattison to give Washington a 21-17 lead. A Joe Kelly interception set up a six-yard TD run by Rick Fenney, and five minutes later Washington had a 28-17 victory and legitimate claim to the Number 1 spot in the polls.

But it didn’t happen. Unimpressed as they were with BYU, voters could not overlook BYU’s 12-0 record. At 11-1, Washington finished Number 2, the highest-ever wire service ranking for a Husky team.