100 years on Montlake 100 years on Montlake 100 years on Montlake: how the UW campus has evolved

How fate, vision and some shameless boosters transformed logged-over land into a beloved campus.

By Tom Griffin | september_1995: Sept. 1995 issue

One hundred years ago, on Sept. 4, 1895, 15 professors and 310 students at the University of Washington packed up their books, abandoned a two-story building in downtown Seattle, and moved to the only building on a scruffy 583-acre tract of land "eligibly situated" outside of Seattle.

The property, part of a territorial land grant for education, was purchased two years earlier for $28,313.75. Today that land—and the buildings on it—are worth more than $3 billion, the home of one of the top public universities in the nation.

But beyond this price tag is the beauty of the campus itself. “It is the most beautiful campus in the country,” says Architecture Professor Emeritus Norman Johnston, ’42. “How can you beat out a campus that has Mt. Rainier as part of the plan?”

It is hard to disagree with Johnston, who has made a career of studying the UW campus. To mark our campus centennial, he has written a new book, The Fountain and the Mountain, chronicling the 100-year history of our Montlake campus.

Like most human enterprises, the history of the UW campus is dotted with remarkable visionaries, shameless boosters and absurd twists of fate. Without financial panics or clear weather, this could have been a quite unremarkable place.

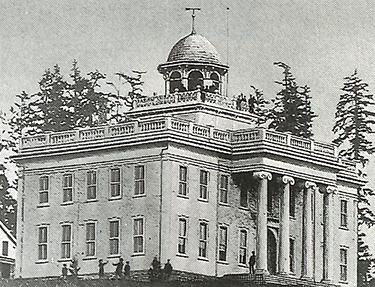

The old Territorial University building sat atop Denny’s Knoll in downtown Seattle.

Take, for example, our flight from downtown. We might have stayed at 4th Avenue and University Street a lot longer if it weren’t for the line of taverns that began to creep up from Skid Road.

Certainly the old Territorial University Building, now the site of the Four Seasons Olympic Hotel, was overcrowded. The library was squeezed into a second-floor hallway and cloakrooms were converted into classrooms.

But casting an eye towards Seattle’s notorious waterfront district, the regents said in a 1890 report that the University was “best removed from the excitements and temptations incident to city life and its environments.”

The hand of fate—in the form of a financial panic—also determined the size of our campus. In considering a move, the Legislature stipulated that any new site be within six miles of the old campus, and planners considered locations at Jefferson Park, Fort Lawton and “Interlaken,” the latter a wedge of land between Lake Union and Lake Washington.

UW President Thomas Gatch favored Interlaken, and told UW alumnus Edmond S. Meany, who had been elected to the Legislature in 1891 on a platform for advancing the UW’s interests.

Meany was the key to the move, says Johnston. He took legislators on tours of all three possible sites and let them make their own decision to choose Interlaken. But the lawmakers were only interested in buying the lower third of the tract.

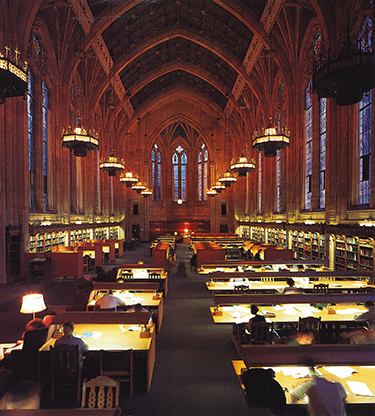

Suzzallo Library’s famous Reading Room, one of the most monumental public spaces in the state. Photo by Stewart Hopkins.

Thanks to the Panic of 1893, the plans to buy the land stalled. In addition, the state couldn’t find any buyers for its downtown property. (It was for sale at $250,000. Now the Metropolitan Tract land and buildings, still owned by the UW and managed by UNICO, are valued at more than a quarter of a billion dollars.)

On the last day of the 1893 legislative session, Meany slipped in a bill to buy the whole Interlaken parcel, which passed and was signed by the governor. The UW had the land, now it needed a plan.

In his later years, Meany said of his beloved UW, “No campus in all the world can equal Rainier Vista. In those rare moments when Mother Nature in kindly mood pulls aside the vaporous curtains we may gaze upon Mt. Rainier, a flow sprinkled three-mile-high pile of rock and ice. A spectacle of unending fascination!”

What Meany failed to note is that, for 20 years, the UW turned its back on its most monumental sight. The first two campus plans ignored the potential of Rainier Vista completely.

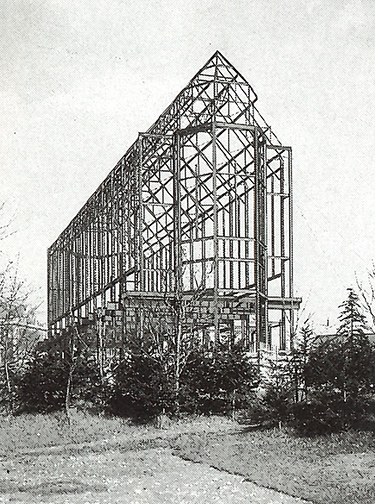

The steel girder outline of Suzzallo Library as it was being built in the 1920s. Photo courtesy of UW Libraries.

In his book, Johnston notes our first campus layout, a 1900 outline known as the “Oval Plan,” incorporated existing buildings in an “uninspired design.” The regents felt the same way and commissioned the Olmstead brothers to come up with something better, yet their 1904 UW plan also ignored the potential vista.

Then the Olmsteads—and the University—were given a second chance. A major fair, the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, would be held on campus and the brothers were hired to lay out the fairgrounds.

Johnston speculates that the weather finally cooperated for John C. Olmstead’s second visit. “Perhaps this time the day was clear, the sun shone, and Mt. Rainier was out in full glory for him. Because, unlike his self-contained and inwardly looking 1904 campus plan, this time he immediately recognized the potential for design drama offered by the distant mountain,” he says in his book.

“Through all the successive plans for the fair, he never let go of the idea,” Johnston adds.

Using a great axis to zero in on a feature was typical of the Beaux Arts style of architecture popular at that time. Most often, that feature was a building or monument, such as Pennsylvania Avenue’s terminus at the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C.

What makes Rainier Vista unique is that a building is replaced by an elusive volcano. “In Rainier Vista we have the most dramatic example of what the Japanese call shakaei, borrowed landscape, in our country,” adds Johnston.

Suzzallo Library at night. Photo by Stewart Hopkins.

By the 1909 exposition, two parts of our campus were a reality—the site itself and the stupendous vista in the heart of it. Yet it still could have been a mishmash of architectural styles and poor planning, warns Johnston.

Once the fair was over, the regents asked the Olmsteads to link the fairgrounds plan to the rest of the campus, but the results were “unsatisfactory,” says Johnston. While there was a Liberal Arts Quadrangle in the Olmstead plan, it was huge. And the upper and lower parts of campus were mismatched like a bad marriage.

It took the vision of Carl Gould, a local architect who also taught at the University, to make the two parts come together in harmony.

Gould brought the scale of the Liberal Arts Quad down to what we have today, explains Johnston. He also designed a great central plaza facing a library where the axes of the Quad and Rainier Vista met—today’s “Red Square.”

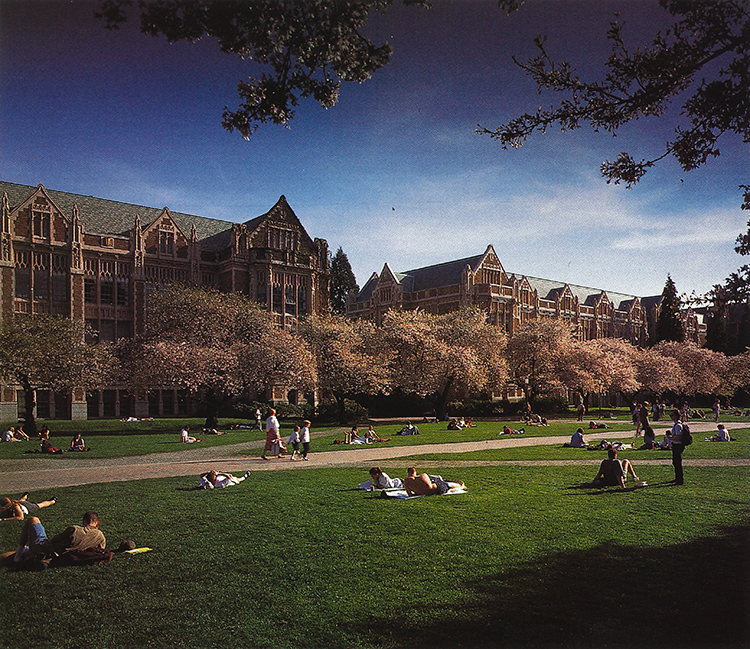

The Quad in bloom. Photo by Stewart Hopkins

In fact, says Johnston, Gould’s 1915 plan is basically still with us, 80 years later. Some of Gould’s ideas, such as framing Rainier Vista with two buildings south of Frosh Pond, are finally becoming reality as the new Chemistry Building and Computer Science/Electrical Engineering Building go up.

More than just the layout, Gould’s imprint on campus can be felt in the way it looks. He led the committee that chose Collegiate Gothic as our official architectural style.

In a later document, committee members explained why they chose this throwback to the Middle Ages. “Because our campus is gray, we adopted a style of architecture which provided a maximum of light,” the report stated. “Because our climate is suggestively cool, we have broken the effect through the use of warm colors.

The UW Faculty Center is a dining and social hall for faculty and staff. Photo by Mary Levin.

“…Starting with a well-lighted factory box, we finally evolved into a local perpendicular Gothic in rich, warm tones—browns and blues, with a rose tinge, for the walls and flat blue-greens for the roof.”

In 1915 Gould designed the first Collegiate Gothic building on campus, Raitt Hall in the Quad, setting the mold for what was to be the campus style for the next half century. He designed most of the other Quad structures as well as his masterpiece of Collegiate Gothic architecture, Suzzallo Library.

More than just environmental concerns were part of the decision to go Gothic, adds Johnston. There is no question that Gould and his colleagues were referring to the great English Gothic campuses of Cambridge and Oxford. If our campus looked like it belonged in England, visiting scholars and potential students might also feel that the University belonged on the same level academically.

Certainly the UW is not alone in borrowing from Gothic architecture. “Many other American universities use it, such as Duke, Yale, the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Chicago,” Johnston notes.

The 1990 Allen Library by Edward Larabee Barnes. Photo by Mary Levin.

But, he adds, “it is not an honest architecture.” For example, Suzzallo Library is a steel-framed building. “The structure is hidden under a skin of bricks. There are no flying buttresses holding it up.”

“The fact is we are not a Gothic people. We’re people of the 20th century, building with new materials such as steel and concrete. We need to respond to our own technology and our own needs.”

That’s why Johnston’s favorite campus building is not a “Gould Gothic,” but rather the Faculty Center, designed by Victor Steinbrueck and Paul Hayden Kirk and built in 1960. “It has purity in its space, modules, form and materials. It is a wonderful building, humane and inviting,” he notes.

But he has few kinds words for the rest of the modernist architecture on campus—such as the 1962 addition to Suzzallo, Sieg, Balmer, Mackenzie and Condon halls. They were “an attempt to build in the modern manner using modern materials. They just didn’t do it very well,” Johnston admits.

At the time officials were rather proud of the new style. The incongruous 1962 addition to Suzzallo was generally accepted at the time, reports Johnston, who was teaching on campus when it opened. “I don’t remember any particular uproar about it,” he says. “I didn’t man the barricades.” Today’s much-maligned Sieg Hall once graced the cover of an architectural journal.

Another library addition marked a turning point in UW architecture. The Allen Library, completed in 1990, was the first campus use of what Johnston and other architectural critics call “contextualism.” These buildings use the same materials and tones as our older, Collegiate Gothic structures, borrowing certain design elements as well.

While Johnston thinks that the Allen Library architect “was too wound up with contextualism,” he feels more recent buildings, namely Cesar Pelli’s Physics/Astronomy Building and Charles Moore’s Chemistry Building, work. “These building are doing their own thing, nevertheless they are compatible with the rest of the buildings on campus.”

Many alumni welcome the return to brick, slate and copper with hints of Collegiate Gothic, but, in Johnston’s view, contextualism may be too safe. “Does the concern for contextual design preclude a bolder architectural achievement?” he wonders.

No matter what the architectural fashion, the basic look of the UW campus is fairly set, he explains. While there will be few additional structures on the Upper Campus, the major building programs will occur in the Southwest Campus, where health sciences, oceanography and fishery sciences, and some administrative structures are planned.

“Once you complete the work in the Southwest Campus, that pretty much closes the books. The wave of the future is in the branch campuses in Tacoma and Bothell,” Johnston says.

If we were to return to central campus in 2095, “what you would see then is pretty much what you see now,” says Johnston. “It would be outrageous if we saw anything very different.”