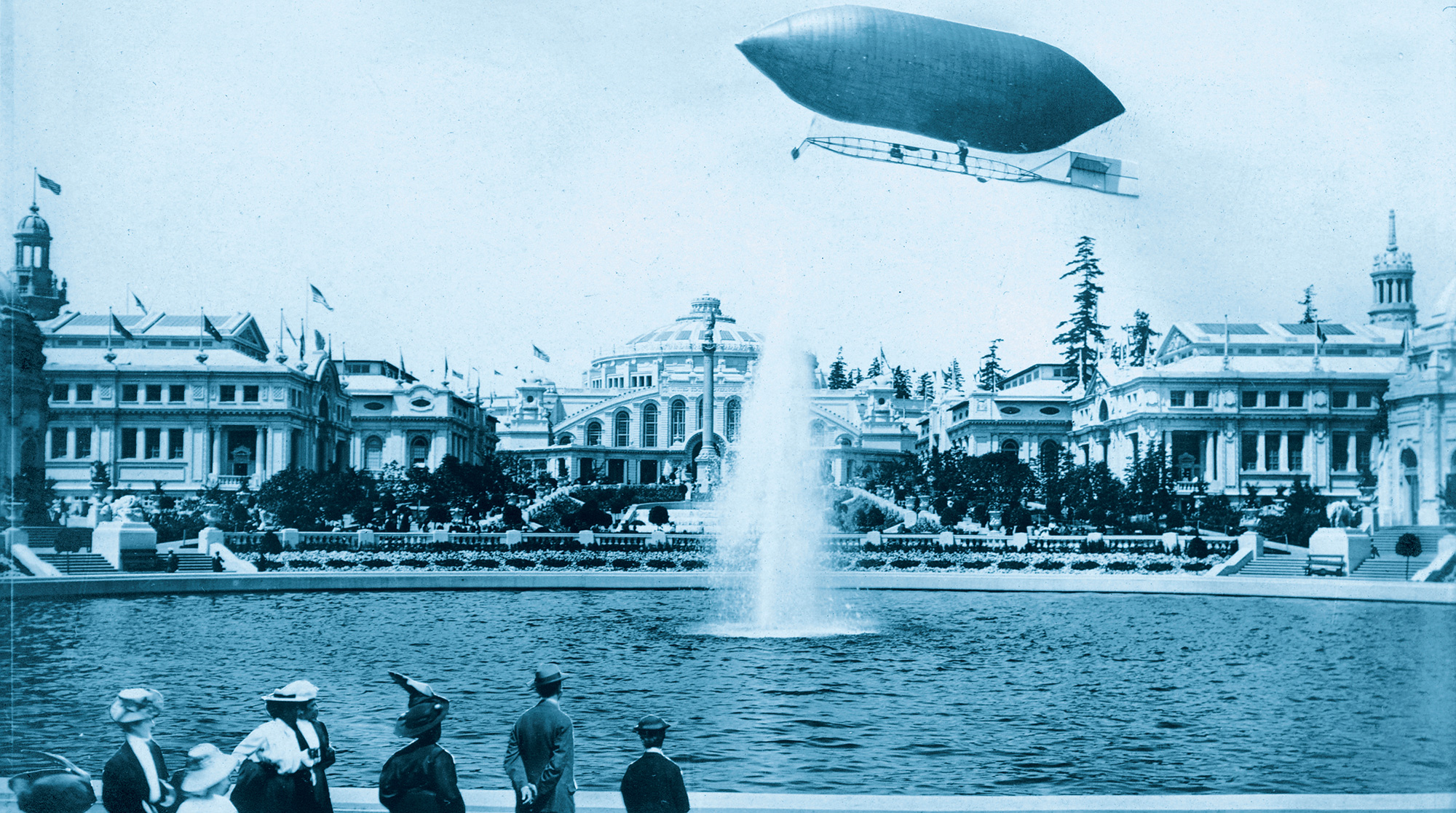

One hundred years ago this summer, a young University of Washington campus hosted the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition (AYPE), a world’s fair showcasing the best of the Pacific Northwest and Alaska. It was meant to be the region’s introduction to the rest of the world—a kind of coming-out party for the Pacific Northwest, and a grand opening of the Seattle campus we know today.

The world took notice. During the exposition’s four-month run, more than 3 million visitors from across the globe sampled the offerings, which ranged from Versailles-inspired formal gardens and exotic foreign cultural performances to astounding new technologies and disturbing sideshow oddities.

Organizers hoped to promote commercial trade with Pacific Rim countries and encourage visitors to fall in love with, and relocate to, the Seattle area. The AYPE met those expectations; over the course of that single summer, publicity generated by the fair changed the perception of Seattle forever. Once considered an unsophisticated lumber town (when it was considered at all), Seattle was reborn as a progressive port city perfectly situated to capitalize on trading ventures with interests in Alaska and Asia.

Organizers hoped to promote commercial trade with Pacific Rim countries and encourage visitors to fall in love with, and relocate to, the Seattle area. The AYPE met those expectations; over the course of that single summer, publicity generated by the fair changed the perception of Seattle forever. Once considered an unsophisticated lumber town (when it was considered at all), Seattle was reborn as a progressive port city perfectly situated to capitalize on trading ventures with interests in Alaska and Asia.

A century later, the AYPE is still visible in the University’s footprint and audible in the city’s heartbeat. Seattleites, whether they realize it or not, are living in the house the AYPE built. Here, in honor of the exposition’s 100th anniversary, is a quick and quirky tour of that singular event.

At left, a promotional poster. At right, “Looking Southeast over Cascade Basin,”

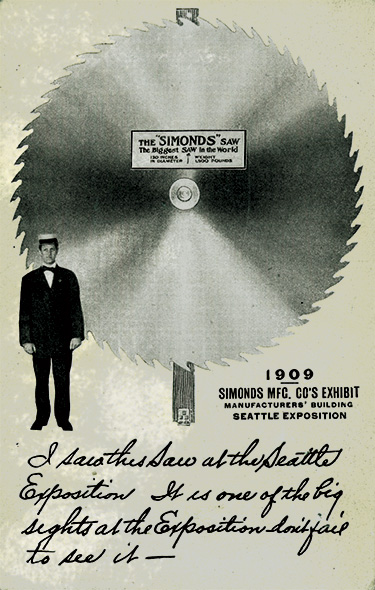

A saw dubbed “biggest in the world.”

At 3 p.m. June 1, 1909, as President William Howard Taft officially opened Seattle’s Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, five automobiles were crossing a starting line in New York City. The Ocean to Ocean Endurance Race to Seattle was on.

The driving conditions were challenging, and at times downright brutal. But with a $2,000 prize, a trophy worth even more, accolades and fame all waiting in Seattle, the racers had plenty of motivation. For more than three weeks, drivers confronted an array of obstacles including heavy rain, snow, high temperatures, dust, rough and rocky mountain passes, flooded roadways and stream crossings, and deep mud with the consistency of quicksand. And then there was the issue that ultimately cost the first team across the finish line its victory—engine trouble.

Four of those five autos were able to make it across the country, through Snoqualmie Pass and over the finish line at the AYPE. Placing first were a driver and a mechanic in a Model T Ford, although they would later be stripped of their win when it was discovered they had replaced their engine during the race. Scandal aside, this transcontinental race was an important symbolic part of the AYPE festivities. Automobiles, still a fairly new phenomenon to the average American, represented innovation, industry and progress.

On June 14 of this year, in recognition of the AYPE centennial, 55 Model T’s ranging in age from 82 to 100 years will leave New York City and reenact the race. Though some of the roads no longer exist, drivers will follow the old route with as little deviation as possible. They’ll even make their nightly stops based on those chosen by the original racers. The reenactors will roll into Seattle July 12 and cross the finish line at the UW’s Drumheller Fountain. Once again, drivers attempting to replace their engines in mid-race will be disqualified.

At left, the Japanese Village and Tokio Café, on the Pay Streak. At right, the Forestry Building with the Washington State Building in the foreground.

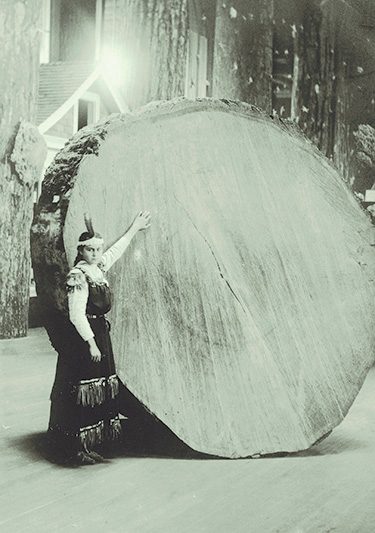

“Block of wood and Indian maid in Forestry Building.”

Offering everything fairgoers could want and then some, the Pay Streak was the AYPE’s midway—with carnival rides, souvenirs, educational exhibits, international food and beverages, and a stunning array of strange attractions. One of the most popular allowed visitors to watch Thousands of fairgoers plopped down 25 cents for the privilege of going into a viewing room and observing the dozing infants, each snug in its own ventilated incubator. Visitors were amazed by the infant habitats, as it would be several years before this new technology was used in hospitals. Nurses (or women dressed as nurses, in any event) were on hand during exhibit hours, and after the crowds were gone they took their little charges to an upstairs area where they cared for them through the night.

These infants gained celebrity status when local newspapers began publishing daily reports on their progress. The exhibit also offered something pretty progressive for the time—hourly child care. Visitors could not only view the babies, but also pay to leave their own kids behind for a few hours to better enjoy the fair.

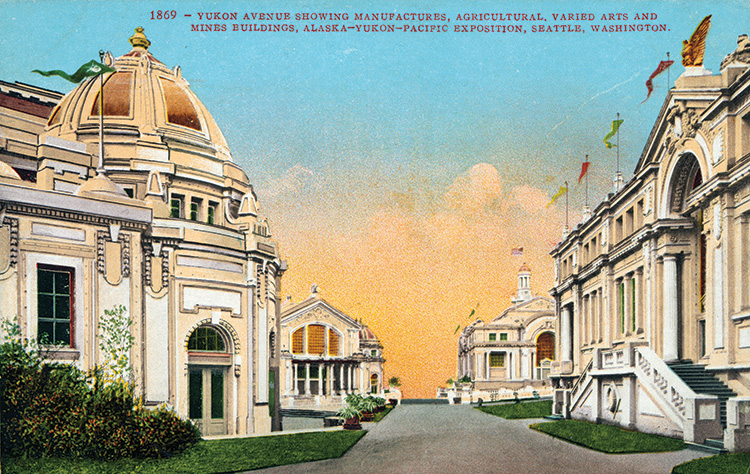

Yukon Avenue.

It was a marvelous scheme—one that could have continued successfully throughout the AYPE if it weren’t for the dirty shoulders. For two weeks, bold young fairgoers had taken advantage of an alternative to paid admission that was, to say the least, subversive. What some referred to as the “Northwest Passage” was actually a sewer line accessible through a manhole just 400 yards north of the fairgrounds. It’s impossible to know for sure who first gained access via sewer—fortunately under construction at the time and empty of anything other than mud and grime—but word spread fast: Bring your own lighting source, and prepare to get a bit dirty.

It was the muddy shoulders that first caught the attention of the AYPE guards, who kept seeing young men dusting themselves off as they emerged from a cluster of buildings just inside the fairgrounds. The manholes were secured, but it is estimated that in the two weeks prior, up to 200 men a day entered the AYPE via the “Northwest Passage.”

Three girls in a sculpture “cut from a single piece of wood.”

One of the most tangible reminders that the UW hosted the AYPE is the Women’s Building, now known as Cunningham Hall. Along with Architecture Hall and the Engineering Annex, it is one of only three AYPE buildings that survives. (Most of the AYPE buildings, though grand in appearance, were simple wood, lathe and plaster structures meant to last only for the duration of the fair.) Though its name has changed, the purpose it serves today—a place for women to gather, learn and grow—is virtually the same as it was 100 years ago.

The two-story structure opened as part of the AYPE and served as a multipurpose venue—a meeting hall, office space, restaurant, nursery and exhibition space for women’s art. Local women’s groups used the meeting hall to host lectures, discussions and receptions. At the time of the AYPE, Washington women were campaigning to pass a ballot measure that would grant them the right to vote, and a spirit of solidarity was in the air. A year later, Washington voters approved the measure by a margin of two to one—a success not duplicated at the national level until 1920.

The momentum of the women’s movement slowed significantly when it was believed the battle for equal rights was won, and the Women’s Building became a victim of its own success. Once a hub of energy and activity for women, it spent the next six decades serving less glamorous purposes, including, ultimately, as a campus storage facility.

As American feminism resurged in the 1970s, local women lobbied to reclaim the venerable building. In 1983, after some substantial cleaning and renovation, the building was reopened as Cunningham Hall, in honor of the groundbreaking photographer and UW graduate Imogen Cunningham, a 1907 alumna. Today Cunningham Hall is home to the UW Women’s Center, and is once again a place for women to gather, share their art, and discuss the issues of the day.